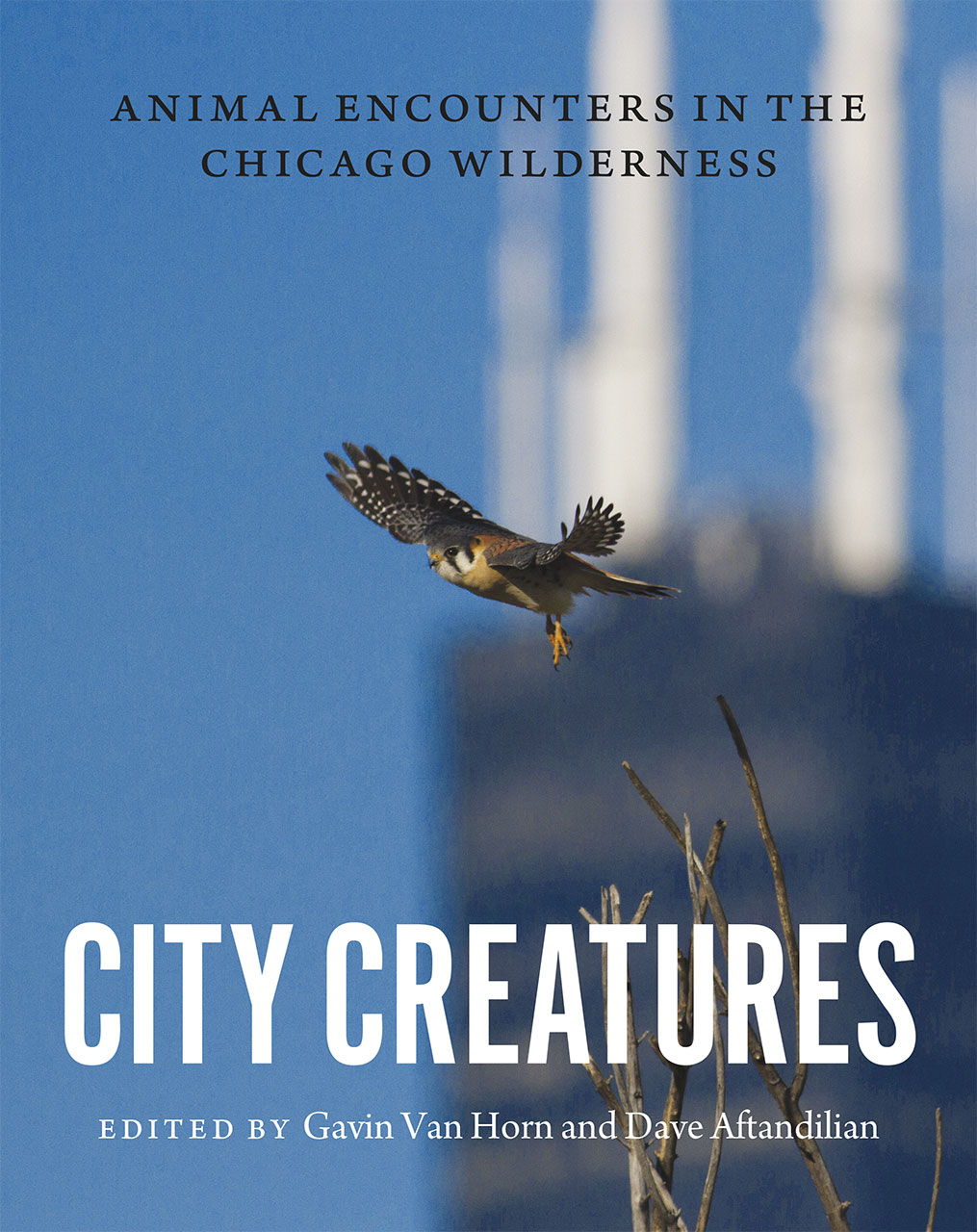

Instead of providing a species-by-species account of the richness of urban biodiversity, a new anthology entitled City Creatures: Animal Encounters in the Chicago Wilderness collects stories that inscribe meaning into the natural landscapes of Chicagoland. Ranging from essays and installation art to poems and tattoos, the book surprises with how centrally it features narrative.

Gavin Van Horn, the Director of Cultures of Conservation at the Center for Humans and Nature, and Dave Aftandilian, a fellow at the Center, were both editors of the anthology, which explores the intersection of animals, religion, and ethics, among other topics. In their introduction, they quote Jonathan Gottschall, a scholar who specializes in the intersection of literature and evolution: “We are, as a species, addicted to story.”

That is, without a doubt, the philosophy that drives this collection. Standing at the shores of Lake Calumet, admiring monk parakeets in Hyde Park, and imagining Illinois in the Paleozoic Era are narratives that underpin several essays and poems, making City Creatures as rich in texture as the biodiversity it describes.

“Part of my job is to think about what paths there might be for people to think about themselves in relationship with the natural world, and how their role matters for the well-being of the places that we call home in Chicago,” Van Horn said at an event at the Chicago Theological Seminary in September.

Chicago is the prime backdrop for such an anthology, he argued, because it “has more biodiversity in its greater metropolitan area than rural Illinois because of corn and soy production.”

The dichotomy that resonates throughout City Creatures, between the manmade and the natural presented in the anthology, is in no way a reproduction of the urban-rural binary, at least not in the Midwest. Nestled within Chicago’s exterior of concrete and asphalt are rich ecosystems, and beyond the city, before rural Illinois begins, are vast expanses of wildlife. The landscapes of Chicagoland could not be more suitable for evoking creative human responses to the nonhuman.

Like Van Horn promised, the thread of Chicago’s ecological history runs deep in many of City Creatures’ pieces. The alewife herring’s colonization of Lake Michigan, for example, and especially the population’s subsequent yearly die-offs, is an olfactory memory seared into the minds of many Chicagoans. The collection reimagines this event through different mediums and perspectives.

In an essay, Curt Meine ponders the ecological sea change that Lake Michigan has undergone, recounting morbid scenes of dead fish piling up on the lakefront. Todd Davis refashions these experiences in verse, with language that is starkly visual: “Against the sand their sides / no longer glisten.” A mixed media installation by Colleen Plumb broaches the issue by depicting the densely layered dried alewives upon a surface in relief.

This multitude of voices and media is where City Creatures triumphs. Some pieces are playful musings on an animal encounter, while others rouse greater moral questions. As a collection of personal pieces, the anthology does not purport to explain why animals are essential in shaping the well-being of the city as a singular unit.

Rather, City Creatures documents emotional and intellectual responses to nonhuman animals, and in so doing, demonstrates how humans define themselves.

There is nothing within the anthology that is not both richly informative and intensely personal. Even Peggy Macnamara’s “Nature on Pause,” a collection of water color paintings of various specimens from the Field Museum, is paired with an essay that describes her personal relationship with the museum’s taxidermy animals and bird nests. In a different vein, René H. Arceo’s “Pescado Blanco en Río Chicago” (“White Fish in Chicago River”), a woodcut that relocates a species of fish native to Mexico’s Lake Pátzcuaro to Chicago River, acts at once as a metaphor for the movement of communities across manmade boundaries and a personal narrative.

There is also a power in some of these works that is not immediately evident when contemplating Chicago’s urban wildlife. The late David Hernandez, once deemed the unofficial poet laureate of Chicago, writes in his poem “Pigeons”: “Pigeons are the spicks of Birdland.” Eli Suzukovich III’s “Kiskinwahamâtowin” (“Learning Together”) discusses the establishment of a prairie restoration garden at the American Indian Center of Chicago as a tool for education. In the comic strip “The Indomitable Water Bear,” Alex Chitty depicts the micro-animal as a means of inspiring resolve in his readers.

As all of these pieces show, human interaction with ecosystems of nonhuman animals reveals more about the ecosystem of human communities than one would expect.

Van Horn’s wistful prose bookends City Creatures: he opens the charming anthology by recounting his first encounter with Chicago’s coyotes and concludes with an essay on the lost buffalos of the tallgrass prairies that once sprawled across Illinois. While it may be difficult to connect with the ecology of a bygone landscape, it is no challenge at all for these words to resonate within many Chicagoans: “If this city can be a home for coyotes, I thought, then it can be a home for me, too.”

Gavin Van Horn and Dave Aftandilian, eds., City Creatures: Animal Encounters in the Chicago Wilderness. University of Chicago Press. 264 pages. $30.