Armando Robles knew that his suspicions of Republic Windows and Doors’ closure were well-founded when, on a late November night in 2008 just days after a mass layoff, he saw nine trucks being loaded with the machinery he operated for work. Several days later, Robles was prepared to take action when the manufacturing company announced its imminent closure—effectively breaking the WARN Act, which requires that companies give warning of closure sixty days in advance. What Robles didn’t know was that the Republic’s closure would be the first in a series of events that would ultimately deliver the factory into the hands of its workers.

Robles first encountered advocates of cooperative business in 2006, when he was sent on behalf of his union—Local 1110 of the United Electrical Workers—to the World Social Forum in Venezuela. “One guy was telling me about co-ops. I don’t pay too much attention, but he says that we can be our own bosses. I ask him how that works, and he tries to explain but I don’t understand much.”

Only after six trying years of mercurial worker-investor relations did workers seriously consider cooperative ownership a viable option. The weeklong, highly publicized occupation of the Republic factory in 2008 won the 270 workers the pay owed to them, but didn’t win them their jobs. When Serious Energy took over the factory in 2008, it re-hired seventy of those workers, only to close down four years later, inciting yet another occupation in the name of workers’ rights. This time, the workers won severance pay, as well as the time to find funding to buy the machinery from Serious.

The freedoms promised by a cooperative factory—secure livelihood, self-set wages, self-governance—were appealing, even if the responsibilities were daunting. In 2012 eighteen of the workers, including Robles, ultimately agreed to buy into New Era at the price of $1,000 each.

Today, New Era stands testament to the ability of a small group of workers to purchase and successfully run its own business. But there were few cooperatives to begin with in Chicago, and fewer have followed New Era’s example. This raises the question—could Chicago better accommodate the cooperative, which has increasingly been discussed as a viable alternative to the traditionally structured business? Does the city of Chicago’s business policy need an update?

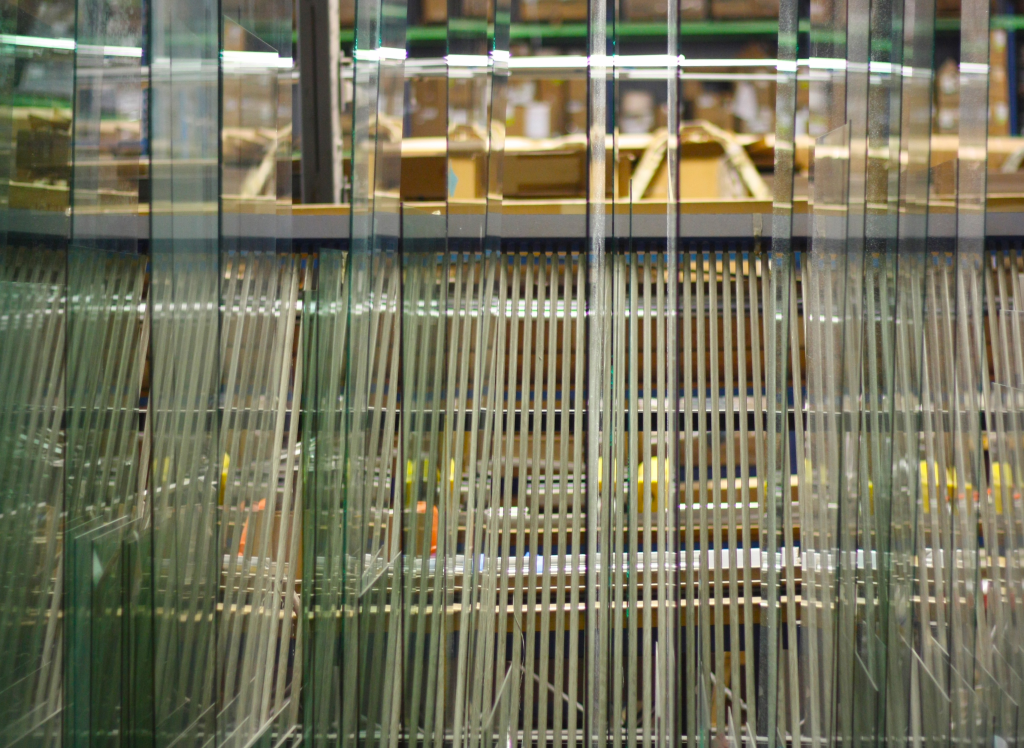

Stopping by New Era on a quiet Thursday afternoon, I find an orange tabby cat eyeing me from beside a row of model windows. The tabby—and another, more elusive cat—belongs to Robles. “We’ve got a couple rats in the factory,” he admits. “The cats are a good solution.”

The entire factory seems to operate on this same principle of resourcefulness. “You see that?” Robles points to a dark corner that contrasts with the uniformly white walls. “When we first moved in, the entire space looked like that. Everything you see—the walls, the pipes, the wires, the machinery—we moved, installed, fixed ourselves. That corner we leave unpainted so that every day we remember our beginnings.”

New Era has been operative for two years now. Robles says that wages today are approximately four dollars per hour higher than in 2013, when they hovered close to the minimum wage, and the company is now nearing self-sufficiency. But the workers, no matter how resilient, would never have been able to bring their cooperative vision to fruition without the financial and technical resources of external organizations.

The Working World, a nonprofit that gives out investment capital and technical support for developing cooperatives, provided the $665,000 in initial capital New Era needed to buy machinery from Serious Energy, transport it, and secure a new factory space. The Working World’s “loan” is not traditional. There are no late payment fees, no exorbitant interest rate; New Era simply pays back the money as soon as it is able to.

On top of that, the workers, most with backgrounds in manufacturing, needed to master financial and management skills that often require years of study. Fortunately, New Era workers had the advantage of being members of United Electrical Workers, a democratic union that operates on what they call “rank-and-file unionism.” Through the union’s progressive structure, New Era workers already had extensive experience establishing a constitution and negotiating contracts on their own, rather than relying on the leadership of a more traditional AFL-CIO union. However, they still received extensive guidance and financial instruction from The Working World, the United Electrical Workers, and the Center for Workplace Democracy, an organization that provides resources to support worker-owned enterprises.

Without these resources––which come from limited sources––it can be even more difficult to incorporate.

Kathleen Duffy, board member of the Center for Workplace Democracy and founder of the Dill Pickle Food Cooperative, believes that investment regulations on cooperatives are unnecessarily harsh, and licensing procedures are too complicated. With regulations better tailored to cooperatives, the Dill Pickle would have gotten off the ground much more quickly.

A change to Illinois’ century-old cooperative business law could potentially improve the standing of the cooperative. State Representative Will Guzzardi, himself a customer of the Dill Pickle, proposed such a change in February. The new law would draw from the accessible language of the International Co-op Association, upon whose values all cooperatives are founded. If approved, the law would mark the first time a workers’ cooperative like New Era, one that doesn’t sell produce, clothing, or groceries, is recognized as a legal entity in Illinois. Though the change in legal status is unlikely to affect New Era’s day-to-day operations, the new law would likely increase general understanding about the aims and structure of cooperative organizations, and potentially ease the investment in and creation of new co-ops.

A change to Illinois’ century-old cooperative business law could potentially improve the standing of the cooperative. State Representative Will Guzzardi, himself a customer of the Dill Pickle, proposed such a change in February. The new law would draw from the accessible language of the International Co-op Association, upon whose values all cooperatives are founded. If approved, the law would mark the first time a workers’ cooperative like New Era, one that doesn’t sell produce, clothing, or groceries, is recognized as a legal entity in Illinois. Though the change in legal status is unlikely to affect New Era’s day-to-day operations, the new law would likely increase general understanding about the aims and structure of cooperative organizations, and potentially ease the investment in and creation of new co-ops.

New policy would have to accompany the change in language. Brendan Martin, co-founder of The Working World, cited lack of city recognition of cooperatives as a minor source of frustration. New Era, whose employees are almost entirely Latino and African American, recently applied for Minority/Women-Owned Business Certification. The goal of this program is to spread the benefit of ownership over a broader demographic, but its application requires exhaustive financial records of each owner. Its process, Martin said, was burdensome for New Era’s many owners, who don’t have financial advisors or accountants at hand the way traditional small businesses may. The certification is within reach for New Era, but its process has dragged on for a year. Martin suggested that the city offer, if nothing else, financial and legal counsel for cooperative workers.

Another approach to cooperative development entails more active financial incentivization. It could take the form of a subsidy, like the $9.6 million one the city granted Republic Window in 1996 to develop the factory in which Robles and his co-workers used to work. That kind of financial support might better serve a cooperative business, which necessarily has strong ties to the community and no interest in searching for the location with the lowest tax rates, as Republic is suspected to have been doing in 2008.

Erica Swinney, a former board member of the Center for Workplace Democracy, thinks that for a more sustainable plan, Chicago should look to cities like New York and Madison, Wisconsin, which have, respectively, set aside $1.2 million and $5 million over five years for the development of cooperative businesses. These budgets are divided between the cities’ existing and developing cooperatives, and the organizations involved have pledged to implement policies that lower barriers for worker cooperatives.

What is the likelihood of a budgetary allowance for this kind of cooperative development in a city whose primary concern is resolving its budget deficit? It’s hard to say. Contenders against Mayor Rahm Emanuel this year took strong stances in support of cooperative development. Cook County Commissioner Jesus “Chuy” Garcia attended New Era’s ribbon cutting ceremony; Alderman Bob Fioretti, a New Era customer himself, allotted significant part of his mayoral platform to cooperative economics. Emanuel, on the other hand, has remained largely silent on the matter.

At the bare minimum, the education system could be changed. Swinney said that most people aren’t raised or schooled to view the cooperative as a viable business structure. “But at the Manufacturing Renaissance [her current organization], we actually offer cooperative structure as a solution to small family-owned business owners that are struggling to find a successor.” The children of these families, often living in the suburbs, lack either the business experience or the interest, leaving the business to ultimately close or leave family hands.

New Era itself will eventually have to confront this generational problem. Its close-knit community of resilient workers has undoubtedly been key to the factory’s transition to cooperative business, but these same workers are aging. Robles has worked for Republic Windows and Doors since 2000, and many co-workers have been working in the window manufacturing industry for longer. “The youngest among us is forty-five, maybe forty-six,” he said.

New Era is looking for new workers to buy into the company, though it wants to preserve the family dynamic of the business; anyone interested in buying in will have to first work a year to ensure that they work well with the group.

It’s been a long haul, but Robles doesn’t regret any sacrifice of time, effort, or sleep made for the sake of the cooperative.

“These people—my co-workers—are like brothers and sisters to me. And I really think that we’ve created something strong here.”