At its core, The Billboard, a play by journalist and author Natalie Moore, grapples with abortion by exploring how several generations of Black women talk about abortion and how it relates to self-care, reproductive justice, community, and economic disinvestment. By showing the conflict between the main characters and a group of anti-abortion advocates, the play navigates important questions surrounding abortion and suggests that there is more to reproductive justice than the right to choose. But the play does not offer the readers or the audience any definite answers; The Billboard demonstrates how we know less than we think, and serves as an invitation to open ourselves up to the perspectives and experiences of others.

The play takes place in contemporary Englewood. Once a flourishing neighborhood, it has lost much of its population and housing stock in the last several decades. Long subject to systemic disinvestment, Englewood is now also threatened by gentrification, which forms the backdrop of the play’s events.

The story begins in the leadup to a local election where the incumbent City council member Cheryl Lewis faces off against Demetrius Drew, a community activist known for his advocacy for Black liberation. However, he is also described as a sheep in wolf’s clothing and there seems to be an unclear, hidden agenda behind his campaign against Lewis. Drew puts up a billboard that reads “Abortion is genocide” right next to the Black Women’s Health Initiative, a “medical clinic and reproductive rights center.”

Drew’s campaign sees gentrification in Englewood as an imminent threat that is pushing out an already declining and under-resourced Black community. The culprit for the supposed danger of gentrification, he argues, is Black women getting abortions, thus “killing” the future Black generation. He claims that the government and businesses are less likely to invest in a community that is considered dispensable and declining. As a result, he believes Englewood will continue to experience divestment until it is taken over through gentrification.

The protagonists are three women who are the pillars of the Black Women’s Health Initiative. Dr. Tanya Gray is the chief practitioner at the clinic, leading its daily operations. Her care for patients reflects her deep dedication to the community’s well-being. Kayla Brown, who is on the cusp of her twenties, is a program assistant at the clinic and preparing for college. She is strategic and knowledgeable about managing the clinic’s public relations over social media. Amid their efforts to change the narrative surrounding abortion endorsed by Drew, she keeps the smaller operations of the clinic running and teaches courage when she publicly shares her abortion story. Dawn Williamson is the chair of the board of directors of the clinic. Her responsibilities primarily entail ensuring that every aspect of the clinic runs efficiently and to lead strategic development initiatives for the clinic’s long-term success. Each woman is a strong leader in their own right and brings insight to the conversations around abortion.

To retaliate against Drew’s campaign and abortion stigmas, they create a new billboard that reads “Abortion is self-care.” Since the community is split on whether abortion should be a legal right or not, it is not surprising that describing abortion as self-care conjures mixed reactions of support, indifference, and hostility. “Self-care,” in this case, is not alluding to the commercialized self-care practices like face masks, brunches, or extravagant vacations, but rather something that has the potential to heal deep intergenerational wounds in many Black families and communities. Hence, to fuel their activism, Dr. Gray, Brown, and Williamson accompany the message of their billboard with the hashtag #TrustBlackWomen which becomes a trending movement on social media within the world of the play.

Through their activism, The Billboard facilitates a conversation about reproductive justice being more than just about reproductive rights. These two terms are sometimes mistakenly understood to be synonymous, but the conversations and reasoning that the three lead women present to the audience illuminate a critical difference between the two.

Whereas reproductive rights refers to having the right to choose to have an abortion, and places the access to these decisions in a legal framework, reproductive justice broadens the concept to include economic, social, and health factors. For example, while marginalized groups have the right to healthcare, they may not have continued access to comprehensive sex education and public programs that help feed mothers, children, and infants. So, while the right to abortion—and reproductive healthcare in general— are a notable foundation, advocates working for reproductive justice know there is more that goes into decision-making and genuine autonomy.

Dr. Gray, Brown, and Williamson grapple with this reality when they confront the public’s reaction to their message of abortion as a self-care practice. They realize that many people believe their concerns are unwarranted because women already have abortion rights. Their response is depicted in discussion amongst themselves about how Engelwood is an example of a community that lacks the resources, programs, and economic support for people to exercise their reproductive rights. For this reason, Williamson and Dr. Gray work hard to keep the Black Women’s Health Initiative open.

The protagonists do not find solace in politicians or policies through their battle. Instead, they find refuge in their community and each other. Dr. Gray, for example, has a sister circle that listens to her and provides emotional support as she shares her grievances with their efforts to change the narrative around abortion. Even though the sister circle only lent an ear, their time, and words of encouragement and support, it meant Dr. Gray knew she was not alone and gave her the energy to keep going.

The Billboard also reminds us that much of the societal problems we face today are intergenerational. Brown shares her experience and reason for having an abortion during her teenage years. Dr. Gray, Dawn, and Lewis’s ages range from the mid-40s to mid-60s. They each share their perspectives of and experiences with navigating abortion in this community, which they feel often lays the world’s problems at the feet of Black women.

Moreover, The Billboard subtly reminds us that all women should be heard. This reminder comes through Williamson, who is on the board of the clinic and is lesbian. In a scene between Dr. Gray and Williamson, Dr. Gray mistakenly implies that Williamson does not understand the weight she feels on her shoulders as a woman fighting for abortion rights and reproductive justice. Williamson responds by affirming that whether or not she and her wife fall pregnant, she knows what it feels like to be disrespected, ignored, abused, and tired. Her sexuality does not make her immune to the pain of having her rights threatened and other societal issues that marginalized women face. All four women contribute to the fight to change the narrative around abortion, women’s autonomy, and reproductive justice. The play makes the argument that no single generation carries the torch, and no age is left behind or left unscathed by societal injustices and prejudices.

Additionally, neither of the women give the same reason for having an abortion. Their reasons range greatly and illustrate their complexities. For example, Kayla shares her story of falling pregnant at seventeen with her high school boyfriend. She was not ready to become a parent and did not want to wait to go to college. Lewis had an abortion for health reasons. More specifically, the doctors told her there was a high chance that giving birth could be life-threatening. Dr. Gray had an abortion because she knew she and her partner were not ready for a child. Each reason for abortion is valued and respected equally.

Despite deftly navigating questions and themes surrounding reproductive justice, the play does not land on any definitive, finite answers. There is no single institution to blame for Englewood’s sordid economic situation in the play, and there is no single reason for having an abortion. There is no single generation to designate as the “social reformers” and no specific generation to blame for the lack of reproductive rights and reproductive justice. There is no single institution to blame for inequality in reproductive justice, and there is no obvious solution to this problem.

Consequently, the audience is left with a harsh but potentially liberating truth that we know much less than we think. How do we find out more?

My takeaway was that the key to gaining more information is being open enough to listen to as many perspectives as possible—something the lead women of the play repeatedly do. To ask is to admit that you do not know. To acknowledge that you do not know is to cut through the fear of allowing yourself to be vulnerable. This vulnerability creates the opportunity to build bridges across different communities and mindsets.

The Billboard reminds us that vulnerability can be our greatest strength when taking steps toward resolving our societal issues.

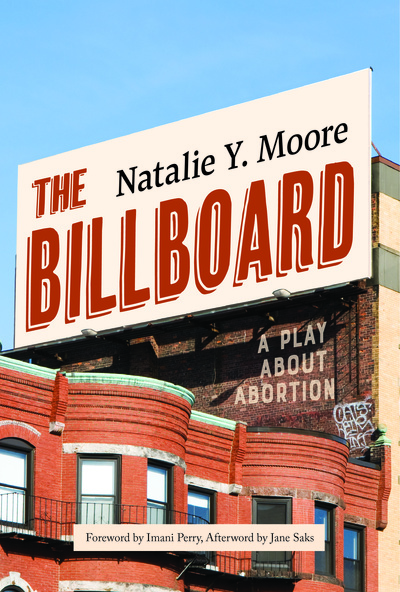

Natalie Moore, The Billboard. $16 (paperback). Haymarket Books, 2022. 100 pages.

Tebatso Duba is a lifelong learner who enjoys exploring and telling stories of people, events, and projects from an optimistic philosophical lens. They last wrote about the Haji Healing Salon.