George Knights is seventy-four years old, which is somewhat rare in the penitentiary, and everyone calls him Mr. Knights because he is our elder. Mr. Knights has served more than two life sentences for a violent crime he was convicted of in 1970. Because he was sentenced before the so-called truth-in-sentencing laws were enacted in the 1990s, Mr. Knights gets to see the parole board, but has consistently been denied parole.

He related to me how he never read a book on the outside, and how he had turned his time in the penitentiary into a mind-building place where he has rehabilitated himself. After he had been incarcerated for a few years, his wife told him she was afraid that, since he had changed so much, she might not recognize him anymore. He says he has changed—but for the better. Now he is nowhere near the same person he used to be. If he were released, his daughter, his grandkids, and his surviving family are the only ones he would have time for, and because of that, plus the years spent here and his age, he would have no problem staying out of prison.

Mr. Knights moves slowly, though his steps seem to be thought out. I’ve had the pleasure of observing him for several months and must say: the only thing he is a danger to is some cookies and a card table.

The United States currently spends over $150 billion a year incarcerating about 2 million Americans like Mr. Knights. Calls for criminal justice reform largely focus on releasing low-level drug offenders, who make up the minority of people held in jails and prisons. Much of the prison population consists of those with violent offenses. In Illinois, individuals with violent offenses do not have the opportunity to earn parole, since the state abolished discretionary parole in 1978.

Before truth-in-sentencing laws, someone with a sixty-year sentence could serve thirty with the chance of parole. But with these new laws, people with violent offenses have to serve most or all of those sixty years—essentially a life sentence. Additionally, mandatory minimum sentencing takes discretion out of the hands of judges, as do the sentencing enhancements. In one example, Illinois’s mandatory enhancement adds a minimum of fifteen years to sentences for murder committed with a firearm.

To achieve real criminal justice reform, we must look for solutions that truly rehabilitate people who were convicted of violent offenses to release them. The United States is the only country that incarcerates this many people for this long. Morally, at some point we must ask: is there not a human aspect to this? Can this money be better spent? Are these individuals not more than their crimes? So why do we continue to hold them contrary to the evidence?

Those deemed “violent offenders” in this article are individuals convicted and serving long term sentences for homicide, assault, robbery, kidnapping or rape (strictly for this op-Ed, this excludes the habitual offenders, serial killers, serial sex offenders, and mass murderers). These are all serious crimes, and those lawfully tried and convicted should be punished. But to what extent? How long is too long? If the ends don’t justify the means, then what is the point?

Justice, retribution, paying your debt, payback, or revenge, call it what you want, but if at the end of the day the point is to make society safer, as well as punish and fix the bad behavior, is that what we’re doing? Can we release the wolves safely at a certain point while making society safer for everyone? Let’s change the thought of being hard on crime to being smart on crime, being right on crime!

Long-term prisoners who have served fifteen or more consecutive years may never get out. These individuals often wind up with a de facto life sentence, essentially being sentenced to “a mandatory term-of-years sentence that cannot be reasonably served in one lifetime,” as defined by the Illinois Supreme Court. The life expectancy for an average male in the United States is seventy-five years, but the life expectancy of someone serving a lengthy prison term is significantly less. One study estimated life expectancy of imprisoned individuals at about fifty years, due to the high incidence of violence, poor healthcare, harsh conditions, poor diet, and lack of exercise in prisons. So, extraordinary long sentences simply cannot be completed within that life expectancy.

There are many different reasons for long sentences, one of the most significant being the 1994 Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act, passed by then-President Bill Clinton. The $30 billion crime bill pushed for “tough on crime” legislation, for “truth-in-sentencing,” “three strikes” laws, and “mandatory minimums.” The bill specifically allocated $10 billion for states that adopted these truth-in-sentencing laws, which mandate that people convicted of violent (and some non-violent) crimes must serve eighty-five to one hundred percent of their sentence.

A common argument behind the need for long prison sentences is that it will prevent those convicted from committing further crimes. But this hinges on the prejudice that paints all imprisoned people as career criminals, and it gives heed to the argument that they are inherently violent, as opposed to someone who engaged in violence at one point or another in their life. As John Pfaff wrote in his book Locked In, “{F}or almost all people who commit violent crimes, violence is not a defining trait but a transitory state that they age out of.”

Locking them up forever and a day negates the fact that a person’s impulsivity, hard-headedness and risk-taking behavior at the age of eighteen or twenty-one will be severely diminished by the age of thirty-five or forty, at which point there is no longer the need for such a long sentence.

The point of the criminal justice system is ostensibly to make society safer, so if we have succeeded in doing so by incapacitating the criminal behavior until a time in which the individual can rejoin society in a productive manner, then why wouldn’t we welcome them back?

Judges and prosecutors also often cite the need for “deterrence,” the idea that a threat of punishment will deter people from committing crime, to justify long prison sentences, especially in cases of severe or serious offenses. However, in 2016 an Illinois Appellate Court recognized that deterrence is no longer a recognized fully legitimate goal.

The more rational and practical deterrent is the probability of being caught. The certainty of an extremely long sentence if the person gets caught won’t matter, as it’s not considered when committing the crime.

“Recidivism,” the likelihood that someone who has been incarcerated will eventually return to prison for another conviction, has been widely studied. But “violent” offenders have the lowest recidivism rate.

In 2016, a two-decade study of recidivism rates among people who had served long sentences in California found that of those incarcerated for at least fifteen years consecutively, one percent were rearrested for new felonies after being released, and ten percent violated parole for technical reasons. Additionally, a 2014 article published by The Marshall Project noted a five-percent recidivism rate for long-term prisoners who were offered liberal arts classes.

The “tough on crime” approach needs to be changed to “smart on crime,” because what we’ve been doing doesn’t seem to be working. Who are we locking up, why, and for how long? If the recidivism rate of certain offenders is very low, then why would we continue to incarcerate them?

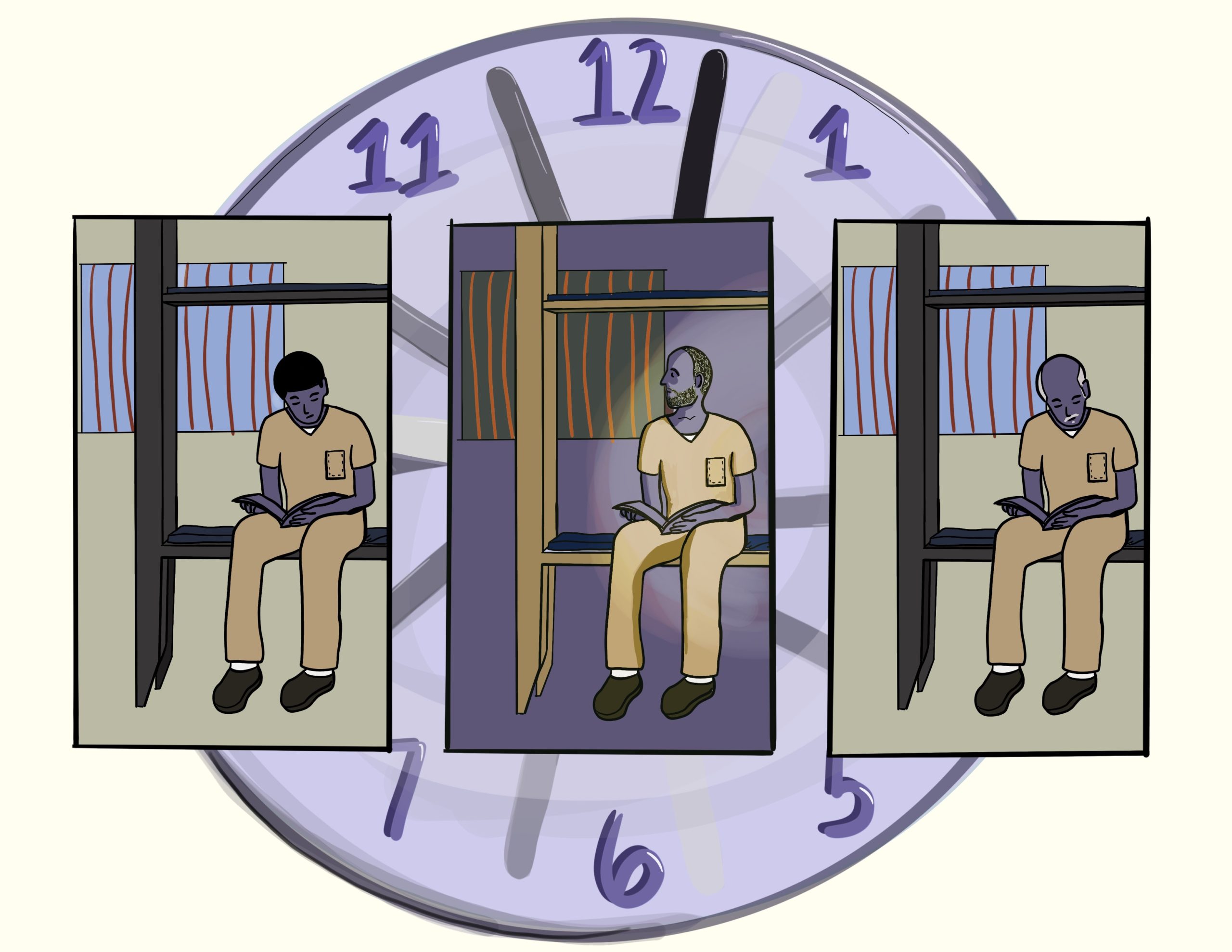

The pattern of declining violence and criminal behavior as individuals get older is called “aging out of crime.” By the time the offender reaches thirty-five or forty years old, they may have spent half of their life in prison. At that point in life, you’re no longer the same person you were when you were incarcerated at a young age. The rationale that the lengthy sentences are needed due to the individual essentially being defined by their crime, instead of acknowledging the fact that they committed their crime, is not justified, nor is society any safer, as is proven by the fact that years later these individuals have not succumbed to their violent environments of prison and instead have changed with age.

Evidence shows that most violent offenses peak between the ages of seventeen to twenty-four, and severely decline after thirty-one. Psychologist James Garbarino, a professor at Loyola University and author of several books, has argued that young adults who lack guidance and self-control grow into adults who, through their own reflection and self-rehabilitation, can become productive members of society.

The U.S. Supreme Court, in its landmark decision Miller vs. Alabama (2012), noted research that found the frontal lobe of young adults may not be fully developed until the age of twenty-five. This is the part of the brain that understands consequences and controls impulsivity and reasoning. As someone matures, their propensity for violence tends to decline. And for those who can grow while incarcerated, the fact that a harsh, violent, maddening, hateful place like prison has not made them even more dangerous after serving a long sentence is a testament to the fact that people are not their worst mistake.

Illinois, which incarcerated nearly 59,000 people in 2020, spends more than $20 million a year on just two of its three maximum-security prisons: Stateville, in Joliet; and Menard, in downstate Chester. About thirty-five to forty-five percent of people in Illinois prisons are doing time for violent crimes.

In Locked In: The True Causes of Mass Incarceration and How to Achieve Real Reform, Pfaff describes how a lot of these costs are put on the State by prosecutors. The County stops paying once an individual hits the state or federal penitentiary.

Now, why is this important toward the cost-benefit of letting out long term offenders? Here’s why: prosecutors get rewarded politically through prosecution, either through promotion or election. What prosecutor has run on a record of leniency or gets a promotion for being lenient? Due to over-prosecution, many more people are not only charged but sentenced to these long terms. Prosecutors have the authority to be lenient and not overcharge people or crimes, but what’s the incentive for being lenient, especially when prosecutors have virtually no limit to the amount of charges they can give? They in turn utilize this power to leverage a plea, even to the point where five people will be charged with a crime when only two committed it, but all go to prison.

This all relates to the cost of imprisoning people for a long time. Imagine the amount a state like Illinois would save releasing only half of its long-term offenders. Imagine what that money could go toward in a cash-strapped state like Illinois: schools, teachers’ pensions, or even crime-prevention programs.

State prisons are often called “correctional” in some form. How long after a person has been “corrected” should they continue to be incarcerated? The statistics clearly show that among individuals who have served at least fifteen consecutive years, reoffending considerably declines, and more so the older they get. Some, if not all, are not even physically capable of committing the same offense, let alone want to. The plan worked; they’re reformed, rehabilitated, “corrected.” Imprisoning them any longer is arbitrary and not doing anyone any “justice.”

Take a look at another country: Norway which abolished life sentences decades ago. The longest sentence for any crime is twenty-one years (though for extenuating circumstances, “preventative detention” can be ordered for extensions of five years at a time). Yet you don’t hear about Norway’s high crime rates due to criminals “not being deterred” or “fearing the consequences.” It appears that Norway has been ahead of the curve now for some time.

Even in the United States there are some states that, in the name of “justice reform” and to reduce their prison population, have successfully released some long-term prisoners. Mississippi, a notoriously conservative, “tough on crime” state, successfully released some of their violent offenders, who make up about forty percent of their prison population. Mississippi reduced the minimum time required by truth-in-sentencing laws from eighty-five percent of a sentence to half, based on behavior while imprisoned. Mississippi safely reduced its prison population by fourteen percent in just three years—without seeing a rise in crime.

In addition to Mr. Knights, I also spoke with others who are serving long sentences in Illinois. I asked Freddie Bibiano, who was incarcerated for more than a quarter-century, why society should believe he has paid his debt (he has since been released).

He gave me a concerned, stern look and nodded his head, clearly understanding the greater meaning and ramifications the question held for, if for nothing else, his own peace of mind.

As he looked up, he said, “All the pain and suffering I’ve caused everyone involved, it changes you. I’m not anywhere near the person I was in that moment. I’m humbled and really appreciative of life and my family. Not ever wanting to put myself, my family or anyone else in society through any of this is my reason.”

I also spoke to Sean Bowens, who had served more than eighteen years at the time. Mr. Bowens is small in stature but big in heart. “I understand what it is to be productive. I no longer want the type of lifestyle that led me here,” Bowens said. “I’m not the same person I was. I see life differently, with higher expectations of myself and life in general. I’m optimistic of my future and incorporating the skills I’ve learned from this time into my freedom when it comes.”

These men have all served decades in an extremely harsh system, yet are optimistic of their future given the chance. These are human beings who have persevered through some unfortunate circumstances without even knowing if there would be the reality of one day getting out. But this further proves the human aspect of the need to release these individuals.

The last person I spoke to had been an employee of corrections for over twenty-three years, having held positions as an officer, in clinical services, and even as a warden. This is a person who has had the chance to observe and deal with long-term prisoners in many capacities for over two decades. While they wished to remain anonymous, the corrections employee said that in their opinion, the long-term violent offenders were the easiest to work with most of the time. They added that if such offenders took advantage of opportunities while they were incarcerated, they could be successful if released. The employee also said there was merit in the argument for their release.

So, can it be done? I’m not advocating to simply open the prison doors and let anyone and everyone out. No matter how or when an offender gets out of prison, there are always requirements of that release: usually some type of parole or probation, consisting of employment, drug testing, house arrest or curfew, and refraining from any criminal activity. So, even when someone is eventually released, it’s not without restrictions. This also isn’t to simply say everyone should be released. Obviously, there should/would be some requirements before that could happen, like so many years in, age, a certain conduct, etc. But the conversation needs to move to action!

I understand victims’ rights advocates would argue against this. They have a valid point and position. However, even if these individuals spent multiple lifetimes in prison, it would never change the past. The crimes they committed were horrible, and they were wrong. But if an individual has truly changed, borne the brunt of responsibility for their actions and is no longer a threat to society, at what point does their sentence become simple retribution?

American prisons are extremely brutal. “Every year spent incarcerated is equivalent to two on the outside,” by many expert opinions. Lack of healthcare, incidents of violence, and verbal abuse can cause or exacerbate pre-existing mental health issues. This is not easy time: fifteen or more years of living in a box, being told what to do and when to do it, losing family, never seeing children, and enduring strip searches, monitored phone calls, letters, food you might not feed a dog, and sometimes conditions that lack basic human necessities. It isn’t a free ride: it’s hard time.

At a certain point, as a society we must be humane and smart on crime. We must realize that you don’t teach someone to act humanely by treating them inhumanely. To hold an individual accountable for the rest of their lives for a horrible moment is, to an extent, counterproductive. At a certain point, you must move past the crime and look at the person.

You can never change the past, but you can change the future, improve future outcomes and right the wrongs. Other nations’ criminal justice models show that we could do this safely. Research has shown that these people are ready to be released. Financially, it would save millions (if not billions) of dollars, and directing that money to crime prevention rather than retribution would make us safer.

It’s for all these reasons that I believe we can safely release people convicted of violent offenses who have served long terms. These aren’t offenders: they are people—people who made really bad decisions many years before, some as long as forty or more years ago. These aren’t the same people that they once were, and they aren’t only that bad choice. These are grown, respectable, responsible, remorseful individuals, who are and can be productive members of society. They are not even capable of committing the same offenses they were convicted of. Some of them are authors, journalists, college graduates, fathers, grandfathers, sons, and brothers.

These individuals have so much more to offer this world, to their families, communities, and to themselves. It’s time to find a pathway to release them. Anyone interested in working for fair systems of review and fair pathways home for people in Illinois with long sentences can contact Parole Illinois at paroleillinois@gmail.com.

Phillip Hartsfield is a social activist who earned his bachelor’s degree in the history of justice with a sociological and psychological perspective, and is currently earning his master’s degree in criminal justice. He last wrote about how new parole laws leave out many.