Chicago law currently allows landlords to evict any month-to-month tenant they want for any reason they want, as long as they give the tenant thirty days’ notice. According to an analysis by the Lawyers’ Committee for Better Housing, every year from 2010 to 2017, one in every twenty-five Chicago renters faced eviction. Around sixty percent of such cases ended in an eviction order being entered. However, tenants are often forced out even in the cases that are dismissed, because they “voluntarily” agree to move out to avoid an eviction record, which can be as detrimental to a person’s ability to find quality housing as an eviction that is carried out.

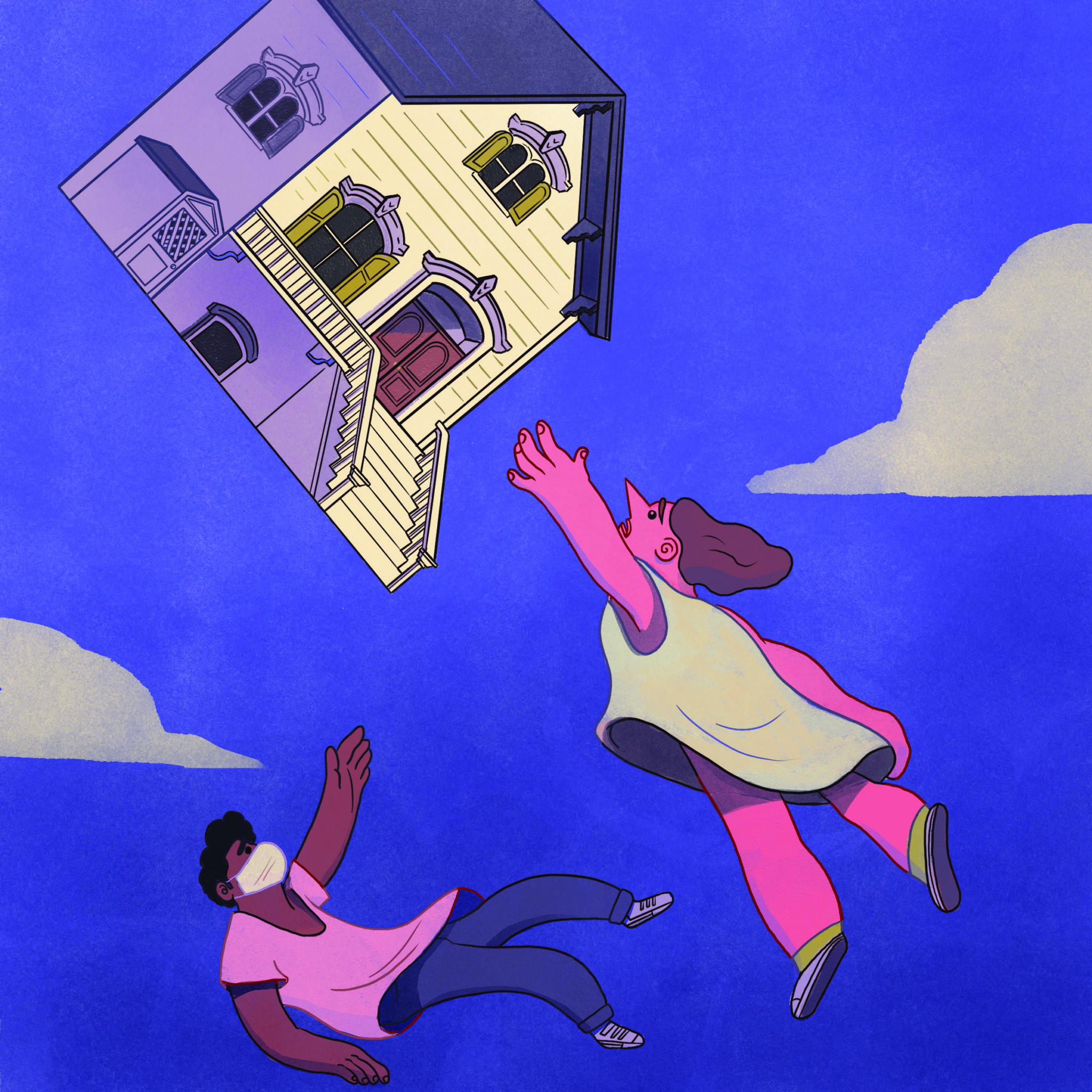

Eviction is a traumatizing and destabilizing experience, and these “no cause” evictions worsen poverty and inequality while often enriching profit-seeking landlords in gentrifying neighborhoods. While the Lawyers’ Committee found that eighty-two percent of eviction filings in Chicago from 2010-2017 made claims for back rent, the number of “no cause” evictions is not insignificant. Further, as a result of Chicago’s entrenched segregation and racial wealth and income gaps, people of color are disproportionately subject to eviction. Organizations like the Metropolitan Tenants Organization (MTO) have been advocating for changes to this system for decades.

According to John Bartlett, MTO’s executive director, requiring landlords to provide a reason in order to be able to evict tenants has been a goal for the Chicago tenant movement since 1981. MTO has its roots in a community convening created that year, which was formed to come up with solutions to address the city’s longstanding housing crisis. One such solution was to create an organization to advocate on behalf of renters citywide. The community also created a platform of three primary policy proposals: a just cause eviction ordinance, tenant bill of rights, and a fair rental ordinance aimed at limiting arbitrary rent increases.

Ultimately, Barlett said that the community’s demands were whittled down to the tenant bill of rights, and after a five-year legislative battle, City Council passed the landmark Residential Landlord Tenant Ordinance in 1986. The RLTO details the rights and responsibilities of landlords and tenants, including remedies for tenants like the ability to withhold rent when landlords refuse repairs. While this legislation was a significant achievement that has helped countless Chicago renters, MTO is still pushing for the passage of the full original platform. Since MTO’s founding, their tenant help hotline has consistently received calls from tenants asking for help after being served with thirty-day eviction notices for lawful conduct like asking their landlords for repairs. MTO has also seen many “mass evictions,” which Bartlett describes as building-wide evictions that occur when landlords want to convert property to higher market rents.

In 2018, MTO joined with thirty-six other housing advocacy organizations to create the “Chicago Housing Justice League,” which has come up with a set of policies and principles to create more equitable housing opportunities throughout the city. The Just Cause ordinance is a major part of the league’s advocacy, and they have been collaborating with members of the City Council’s Latino and Progressive Caucuses, who plan to introduce the ordinance this Spring, Block Club Chicago reported earlier this month.

In an interview with the Weekly, the ordinance’s chief sponsor 25th Ward Alderman Byron Sigcho-Lopez said, “Evictions are a traumatic action… We cannot allow developers and corporations to continue to write legislation and impose their will at the expense of the vast majority of people.” Instead, Sigcho-Lopez has been working with MTO and the rest of the Chicago Housing Justice League to craft a new Just Cause ordinance, with help from other members of the Progressive Caucus and 48th Ward Alderman Harry Osterman, who Mayor Lori Lightfoot appointed as the chair of City Council’s Committee on Housing and Real Estate last May. As the former director of the grassroots community group the Pilsen Alliance, Sigcho-Lopez is deeply familiar with Chicago’s long-standing dearth of affordable housing, especially for communities of color. After he was elected to City Council last year, Sigcho-Lopez restarted conversations around Just Cause, a proposal that had been dormant during the developer-friendly administration of former mayor Rahm Emanuel.

While the ordinance is still being finalized and is sure to face opposition from landlords, developers, and their attorneys, the main thrust of Just Cause is that the ordinance requires landlords to give an actual reason for eviction—like nonpayment of rent or breaking a lease term—and it expands the notice period, with longer required notice for larger rent increases. In more ambiguous situations, such as when a new building owner is converting a building to non-rental units, or when an old owner sells a building to a developer, the ordinance would require the owner to either give people time to relocate or pay a fee for relocation assistance. Once it is finalized, Sigcho-Lopez plans to introduce the ordinance as soon as possible and is hopeful that it will pass, especially given the fact that Lightfoot said in a speech to the City Club in February that she supports Just Cause and other tenant protections. However, the bill will surely still face significant opposition; a similar proposal from then-1st Ward Alderman “Proco” Joe Moreno was tabled in 2018 after outrage from Chicago landlords.

Sigcho-Lopez’s work on affordable housing has become even more urgent given the current pandemic and the statewide shelter-in-place order; social distancing is impossible when you don’t have shelter, and nationally, millions of people have lost their jobs and source of income in the past month. He also suggested a delay in property tax assessments to provide relief to homeowners, and proactive rental assistance to ensure that no one is saddled with extreme debt or forced from their homes during this crisis. However, in order to enact such measures, Governor J.B. Pritzker would have to lift the current statewide ban on rent control, which he has the power to do in an emergency, according to a legal memo commissioned by the Kenwood-Oakland Community Organization. However, Pritzker has asserted that he does not have the legal authority to lift the ban on rent control; his office has not replied to a request for clarification. In the absence of such a “rent freeze,” 47th Ward Alderman Matt Martin last week proposed an ordinance that would give renters a twelve month grace period to pay rent if they lost income due to the coronavirus crisis. It has seventeen cosponsors.

Even before the current economic and public health crises arose, organizations like the Lift the Ban Coalition have been pushing state legislators to repeal the Rent Control Preemption Act, which was pushed through the General Assembly by the ultra-conservative American Legislative Exchange Council in 1997 before residents could even debate the benefits and drawbacks of such a policy, the Reader reported in 2017. Sigcho-Lopez emphasized that the Just Cause ordinance would be most effective if rent control is also enacted—otherwise landlords could just hike up rent for whoever they don’t want in the building anymore, and then evict them for nonpayment.

Tenant protections like rent control and Just Cause are essential because they limit arbitrary increases in rent so that people are not displaced and neighborhoods are able to sustain a diverse range of incomes. As J.W. Mason, an economics professor at the John Jay College of Criminal Justice in New York City, testified in front of the Jersey City, New Jersey City Council in November, there are moral reasons why long-term tenants have a legitimate interest in being able to stay in their homes—but there are also several economic justifications, such as the fact that high tenant turnover leads to less stable communities, which discourages neighborhood investment.

Most opponents of rent control ignore the fact that the two rent control bills proposed last legislative session did not apply to new properties or improvements made to existing buildings, so landlords would still be able to make profits for their additions to and management of the existing housing supply—rent control merely captures the windfall profits that automatically accrue due to the scarcity of housing or increased investment in a particular neighborhood. In addition, rent control could also help to mitigate the current trend where the private housing market largely builds new units for upper income buyers and luxury renters (with a few notable exceptions in Chicago).

As retired Harvard University law professor Duncan Kennedy testified in support of proposed rent control bills in Massachusetts, “Giant rent increases with no equivalent improvement in housing conditions, along with displacement, represent a gigantic forced transfer of wealth from middle and low income tenants to landlords and developers.” That money would be much better spent ensuring that housing is not such a scarce resource, because it is a human right. Beyond the Just Cause ordinance, Sigcho-Lopez emphasized additional tenant protections such as the right to counsel in eviction proceedings, which reports from the Lawyers’ Committee and the Reader have shown to decrease the likelihood of eviction. There is also an urgent need to increase the supply of affordable housing, which governments can do through social housing—housing built and owned by municipalities (with funding from the federal government) that is leased at affordable rates and universally available to city residents.

While Chicago has needed major housing policy reform for years, the coronavirus crisis is making it even more apparent that Just Cause is one of many policies that will be necessary to increase and preserve Chicago’s affordable housing supply. As a January report from the Harvard Joint Center for Housing Studies concluded, “only the federal government has the scope and resources to provide housing assistance at a scale appropriate to need across the country.” Increased federal support for state and local governments is not very likely, but there are still many measures that state and local policymakers could take to make sure that no one is displaced as a result of the current public health and economic crises. Ultimately, like the RLTO, Just Cause could be a crucial step that could help thousands of Chicago renters.

Bobby Vanecko is a contributor to the Weekly. He is a second-year law student at Loyola University Chicago interested in criminal law, and interns at First Defense Legal Aid and the Westside Justice Center. He last wrote for the Weekly advocating for free, carbon-free, and police-free public transportation in the city.