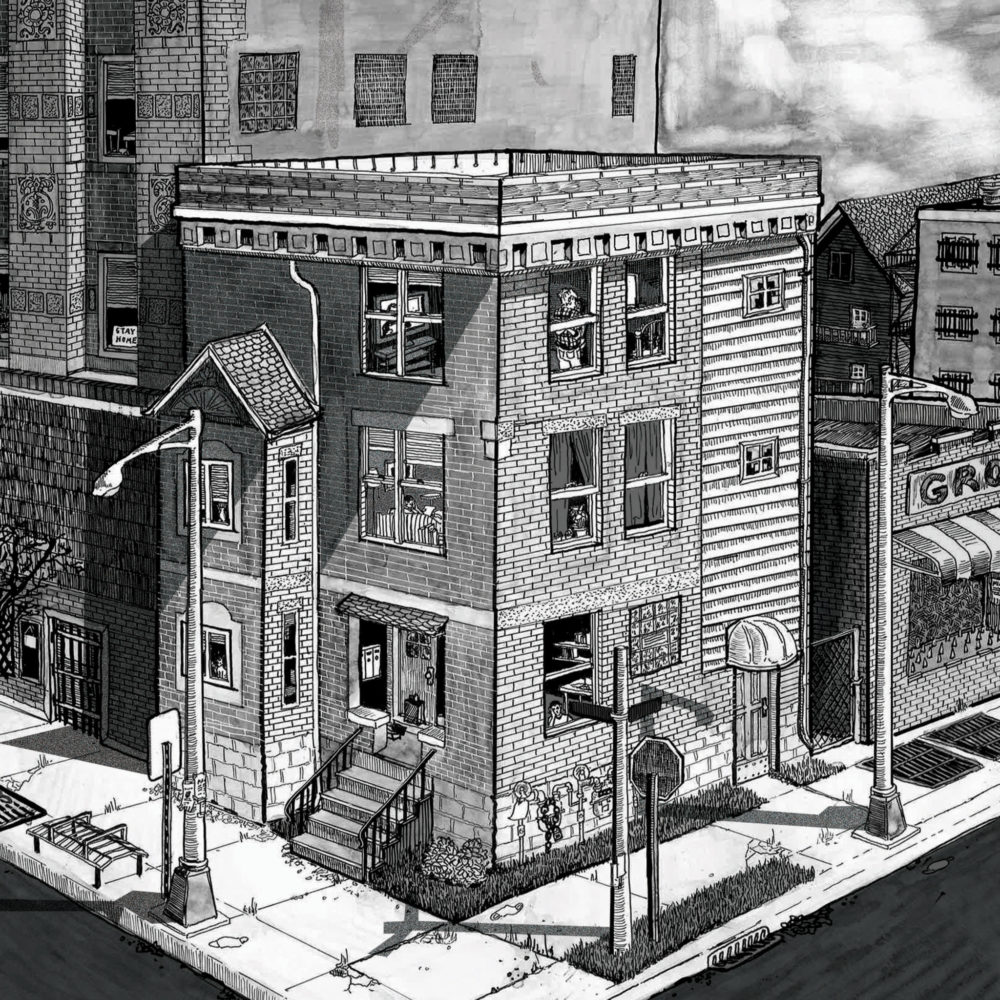

Every night in Illinois, street outreach workers patrol neighborhoods plagued by gun violence. They mediate conflicts, counsel those at risk, putting their bodies between potential shooters or try to convince young people to put down the guns. They’re first responders to a public safety crisis that conventional approaches haven’t solved.

What many don’t realize is that these frontline peacekeepers face extraordinary danger on the job. Recent research from our team at Northwestern University found that Chicago’s outreach workers are more likely to be shot or shot at than police officers and many suffer from the trauma of every duty of their jobs where they (and their participants) are exposed to violence, poverty, and systemic barriers.

Yet despite performing this essential public safety work, many workers struggle with a basic, fundamental need: stable housing.

This reality points to a profound intersection of crises.

It is well established that returning residents and their communities face significant public health challenges. Reentry programs are designed to ease this transition, with stable housing being a critical component, particularly during the vulnerable first year after release, when it serves as the foundation for accessing employment, services, and rebuilding community ties. As detailed in a recent op-ed, returning residents and individuals with justice system involvement face multiple barriers to employment and stable housing. And the stark reality is that 80 percent of people at high risk for gun violence have an arrest or conviction record, creating a deadly cycle of instability that ripples through entire communities.

This isn’t just a housing crisis. It’s a public safety crisis.

The connection between housing instability and violence is clear. A recent survey of street outreach workers in Boston, Chicago, and New York found that 68 percent reported their income was insufficient to meet household needs. About a quarter couldn’t pay their mortgage or rent in the previous six months. Many are working second jobs (an additional twenty-two hours per week on average) while trying to prevent the next shooting. They are groggy from long hours and traumatized from the constant exposure to gun violence—and many are couch surfing, trying to find a place to live, so they can get back to their vocation of trying to save lives.

The same study revealed that most outreach workers are parents or caretakers with a median of two children. When these essential workers lack stable housing, entire families are impacted. Children may have to move schools as their parents search for housing, and communities lose the stabilizing presence of those most committed to peace.

But it’s not just the outreach workers who are struggling. Our research also found that the participants they serve face significant housing instability as well. Among community violence intervention (CVI) participants in Chicago, 25 percent reported their current housing situation was unstable or very unstable. Most telling, 60 percent of those who had served time in correctional institutions reported experiencing housing instability at some point in their lives.

Despite this need, the majority (71.5 percent) reported living in someone else’s home—with family members, partners, or non-relatives—rather than having a stable place of their own. For younger participants ages eighteen to twenty-four, the situation is particularly dire, with 17 percent reporting they’ve stayed in at least three different places in just six months. These young people, who are trying to change their lives with the help of outreach workers, find themselves bouncing between temporary living situations while trying to avoid the violence that surrounds them.

read more about the people interrupting gun violence here

Jobs. Block Clubs. Investment: How Chicagoans Are Interrupting Violence at its Roots

The Home for Good program would invest $103 million to create a coordinated system between the Illinois Housing Development Authority and the Illinois Criminal Justice Information Authority to both support community violence intervention workers and help people with criminal records find and maintain stable housing. Through a combination of developing affordable housing units, providing rental assistance, offering wraparound support services, and establishing a training institute, this program addresses both immediate needs and long-term structural issues.

Critics might question the cost, especially during budget constraints and the tsunami of federal cuts. But for every dollar invested in Home for Good, more than $6 would be injected back into the Illinois economy. This program would save taxpayers an estimated $650 million over three years through reduced incarceration and increased economic activity.

Beyond economics, there’s a human urgency to this program. We ask street outreach workers to be first responders to violence in our most troubled neighborhoods. We expect them to interrupt cycles of retaliation, often working multiple days and nights without rest, holidays, and weekends. And research shows their work is having an impact. Violence intervention programs have seen participants’ arrest rates drop by over 70 percent. Yet we’ve failed to ensure they have the fundamental stability of housing.

The Home for Good program represents a shift in our approach to public safety—one that values prevention over punishment and recognizes housing stability as essential infrastructure. It acknowledges that the people doing the difficult work of violence prevention deserve the basic security of a roof over their heads.

By supporting outreach workers and those they serve with stable housing, we build resilience into our communities. We break the cycle of incarceration, homelessness, and violence that costs taxpayers billions while devastating neighborhoods.

Housing isn’t just about shelter—it’s about safety for all Illinoisans.

Soledad Adrianzén McGrath is the Executive Director of The Center for Neighborhood Engaged Research & Science (CORNERS) at Northwestern University. Andrew Papachristos is a Professor of Sociology at Northwestern and the Faculty Director of CORNERS.