When I visited La Catrina Café last Saturday night, my view of the commotion inside was at first restricted by the lines of condensation on a large window. I stepped closer to inspect the crowd: books held to their chests, they shuffled eagerly around a busy table. As they came and went, I caught a glimpse of one small figure, bent over slightly, signing a copy of his book. It was Japanese photographer Akito Tsuda. He looked up at and I noticed his smile, one that encompassed the entirety of his face. I entered the venue, and Latin music wrapped around me, ushering me inside to a gracious assembly of Pilsen locals.

The café was entirely emptied of furniture and instead filled with people who slowly circled the room with eyes leisurely sliding from photograph to photograph. Lines of children weaved between the adults, holding hands as they passed under the friendly conversations of their parents and grandparents. I could overhear exclamations of recognition as people saw their friends and families captured as works of art on the wall. “That’s me!” one woman said, pointing to a portrait of a young girl. “I remember that day!” The atmosphere was overwhelmingly one of nostalgia, as the Pilsen community gathered to celebrate not only the photography, but also the subject of the photography: themselves.

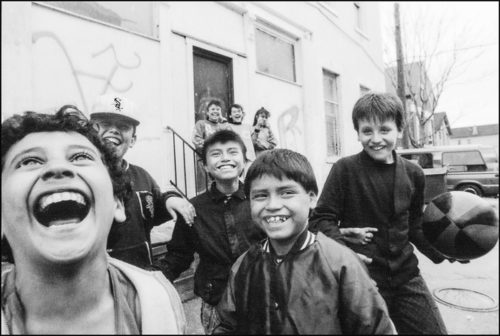

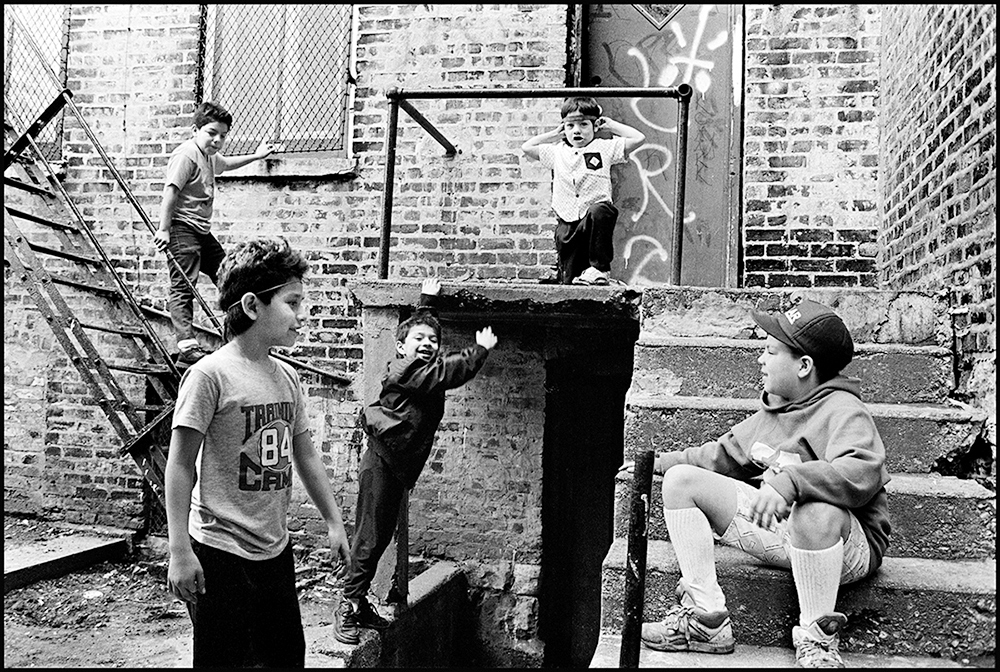

Born in Hamamatsu, Japan, Akito Tsuda came to Winnetka, Illinois in 1989 on a work visa. He then moved to Chicago in 1990 to study photography at Columbia College. He stumbled across Pilsen while working on a class project, and slowly forged an intercultural bond with the Latinx locals as he captured their daily lives in his documentary-style work. The subjects of his black and white photography ranged from cliques of Mexican-American children to lone vagrants. His collection contributed to the historical record of the height of Pilsen’s Latinx culture in the nineties.

Tsuda’s current stay in Pilsen is even more impactful, taking place during this time of gentrification and cultural erasure. To promote the release of his second book of photography, which celebrates the vibrancy of the Latinx community, Tsuda again chose Pilsen’s La Catrina Café for the opening of an exhibition of his work.

As the music subsided, Ilene Palacios, a co-manager of Cultura in Pilsen, addressed the crowd before Tsuda’s speech. She spoke about her organization, which is a community and arts space currently residing in La Catrina Café and hosting exhibits and workshops for Latinx artists.

Tsuda truly “had a yearning to come back” to Pilsen, Palacios told me. One year ago, he began independently sharing his photographs on Facebook. Due to an overwhelmingly positive reception, he then published them in a second edition of his book, entitled Pilsen Days. Palacios knew she wanted Cultura to host his opening exhibition and book release, along with the help of Columbia College, Tsuda’s alma mater. Tsuda’s photography is not just a part of the lives of Pilsen locals, it is the life of Pilsen. It captures the Latinx community that created for itself a thriving cultural space in the heart of the West Side. Cultura works to make this kind of work more accessible, and garner a sense of connection between the neighborhood of Pilsen and the art that grows out of it.

Following Palacios, Tsuda climbed onto the small stage while yells of his name came from members of the crowd, old friends and classmates who had come to support his work. He lifted the microphone shyly to his lips and simply chuckled at his lack of words, overcome by such a warm welcome back. “Thank you so much…” he said, letting his clipped sentences trail off as he lost his voice to his emotions. One man began yelling, “Bravo!” and the crowd broke out into a second round of applause that seemed to imbue him with some strength to speak.

Tsuda began talking, quietly, of the story of his life. Undeniably uncomfortable being the center of attention, he said, “You may think I’m good at talking to people, but I am very bad.” He explained that he first came to Chicago in the nineties to pursue a photography degree at Columbia College, yet spoke little to no English and knew no one. During his second year, he began a project that brought him to Pilsen. “I don’t know what to do,” he recalled. “I just started having a camera. I didn’t know it was called Pilsen. I just started working.”

He began pointing to a handful of his photographs, even identifying in them one of his good friends, Peter. He drew the focus toward the community that he grew to love more than himself, emphasizing the role that the people in the room played in his art and its success. When he worked in Pilsen, he said, “Everyone accepted me. People still accept me. They didn’t care. Peter used to call me chino chino!”

Tsuda shared how he was dependent upon the support of the community to push himself further in his work. At first, he said, he wanted just to satisfy his own ego—competing with his classmates and lacking a clear purpose. Then, he discovered Pilsen: “This is proof that I could work.”

Pilsen reminded him of his childhood, as he observed the strong familial bonds that served as the foundation of the neighborhood at large. He pointed to a picture in the back of the room. It was of a family of four, squeezed together on a couch, beneath their laundry hanging on a wire. Tsuda indeed found a family of his own in Pilsen, one built upon unconditional acceptance. And this family is what he photographed. “I have a responsibility to take a picture,” he said, ending his speech with the driving force behind his passion. He found a purpose not just in Pilsen, but also through the people that inhabited it.

As Tsuda wrapped up his talk, someone yelled boisterously: “Welcome back, welcome back!” Others followed with whistles, shouts, and a great amount of applause as he stepped down from the stage. Immediately, a mass of old friends and locals swarmed him as they shared their stories and gave him an endless string of handshakes and embraces.

And as I was jostled slowly to the edge of the room by the growing ring of people around him, I caught again a gap in the commotion and spotted Tsuda with his arms around old friends. Yet this time, his broad smile appeared not just to overwhelm his face, but imbue his entire narrow frame with a glow of gratitude that could only come from finally, after twenty-five years, returning home.

Akito Tsuda, Pilsen Days. $50. 184 pages. culturainpilsen.com

Support community journalism by donating to South Side Weekly

Real lives, real neighborhood.