Growing up in Pilsen in the 1960s, Diana Solís wandered the streets with her mother, marveling at the Bohemian architecture and imagining the buildings were “something out of a fairy tale.” That sense of imagination and eye for detail would take Solís around the world, photographing and participating in social movements and everyday life.

But she remained firmly rooted in Pilsen, known back in the day as 18th Street. More recently, during the pandemic, Solís began taking early morning walks around Pilsen. She rediscovered her neighborhood—and her love for photography.

Solís was born in Monterrey, Mexico; her parents had moved back and forth across the border and worked picking cotton in Texas. After her father got a job as a machinist at the Rock Island Railroad in Chicago, her mother traveled from Mexico with Solís, still a baby, to join him. She and her seven siblings grew up in Pilsen in a home stuffed with “rickety shelves” of jazz records and books—“everything from magazines to Mexican poets [and] Irish poets.”

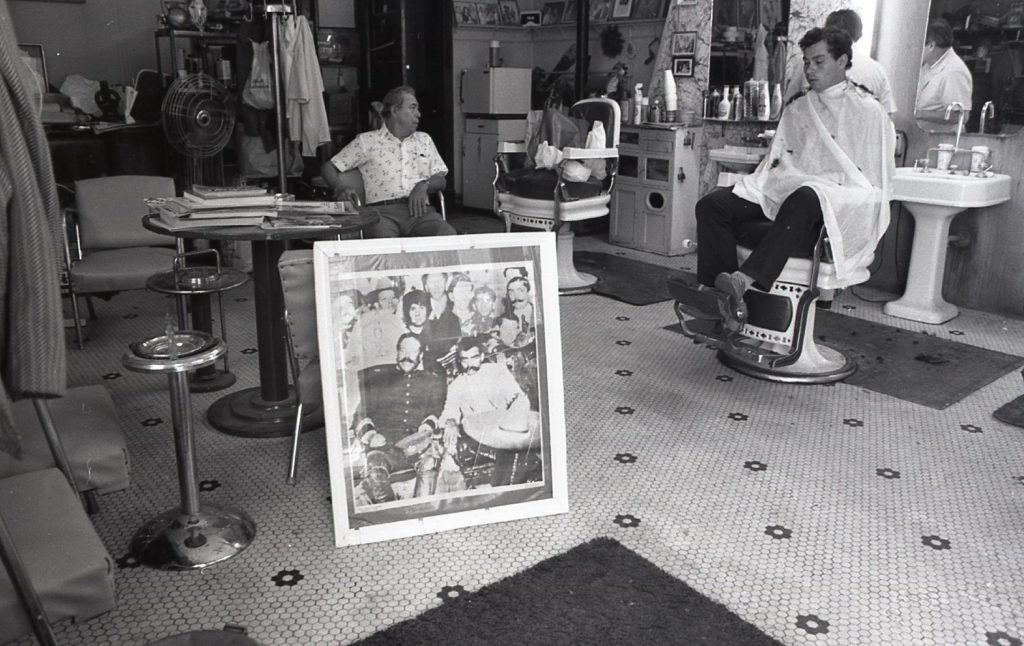

Solís got her BFA in photography at the University of Illinois at Chicago and delved into photojournalism, shooting in Pilsen and other neighborhoods for the Lerner Booster local newspapers, the West Side Times, and the Chicago Tribune. “Neighborhood stuff, you name it: supermercados, family struggles or store closings or unique places opening in the neighborhood.”

She also photographed the rising gay and lesbian movement (as it was known then), protests with ACT UP, and gay and lesbian pride parades in the city. “In the early ’80s, there were still bar raids,” she noted.

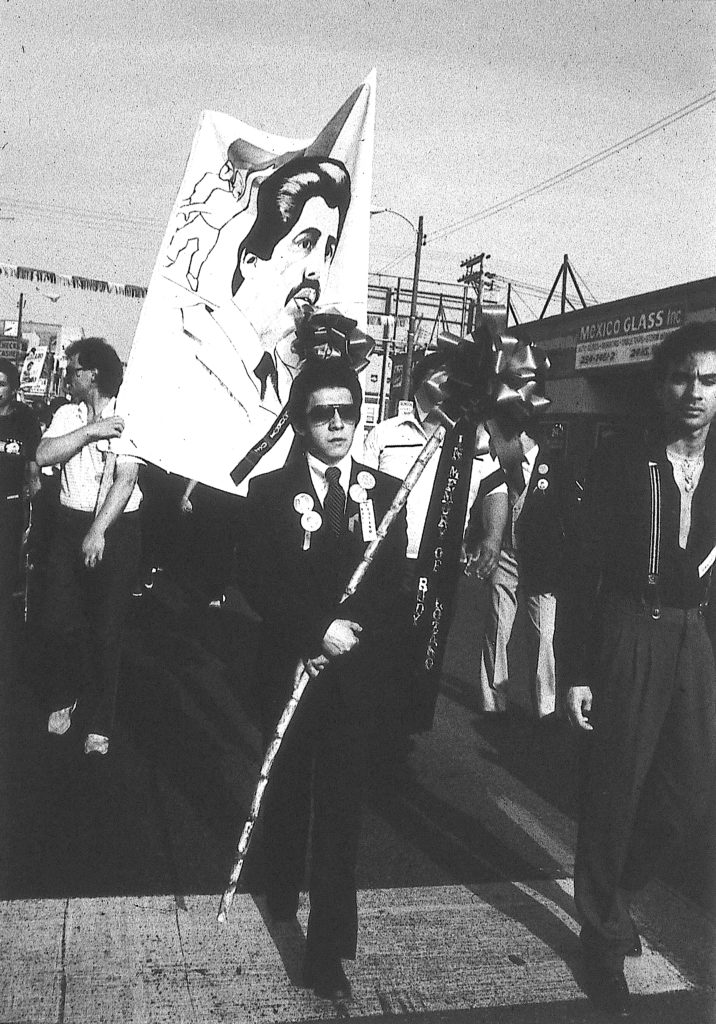

“This was an era where there were a lot of things happening—demonstrations, anti-war stuff in the late sixties, Casa Aztlan, the Chicano movement. I was working with grassroots organizations, becoming a youth organizer. And the artists who were doing murals were incredibly inspirational,” she said.

As a kid, Solís’s family would take annual trips to her hometown of Monterrey. She started going to Mexico City later to explore the museums and culture, and in 1983 she moved there. She did odd jobs to survive, working as a secretary and photographing cakes in a French bakery. A friend helped her get a job at the television station, Televisa, basically as a “paparazzo,” she said.

“My job was to photograph the movie stars. It wasn’t really what I wanted to do, but it was a job and I needed a job… After a year, I got fired because my way of photographing was much more documentary-style—very Rolling Stone. The editors hated it. They were like, ‘We have to have the woman in three changes of clothes, she has to look sexy.’ It was an incredibly sexist environment. I had to wear heels on the job and a skirt.”

She also co-founded a lesbian women’s café and feminist center in Mexico City called Cuarto Creciente.

In 1997, Solís lived in Paris and traveled around Europe. On first stepping out of the train in Paris, at age forty, she was so overcome by the majesty of the famous city that she cried.

By the turn of the millennium, she was back in Chicago and focused on painting and drawing, creating a prolific stream of surreal, whimsical and fantastical works. Her thousands of photographs and negatives were stored away, and she stopped thinking of herself as a photographer. But during the pandemic, that changed.

“In late 2019, I sort of timidly started getting back into it,” Solís explained. “And then in 2020, I started going out and walking in the morning. I had my camera phone, an older-model iPhone at the time, and I started to just take pictures of things that I hadn’t seen before—because we were just always on the go and moving so fast that I really didn’t pay attention to how the neighborhood I know has been changing.”

She dug out a DSLR camera a friend had given her, and learned how to use it—a whole different world from the analog photography she knew so well. She also got an updated iPhone. Though she had spent so much time in Pilsen, she was seeing it in a new way.

“What happened for me, what probably happened for other people, too, during the pandemic and the lockdown, was that you really got to see things that you haven’t seen in a long time,” she said. “I slowed down tremendously. And that slowing down enabled me to look at things and look at the community in a different way. I call it slow photography now.”

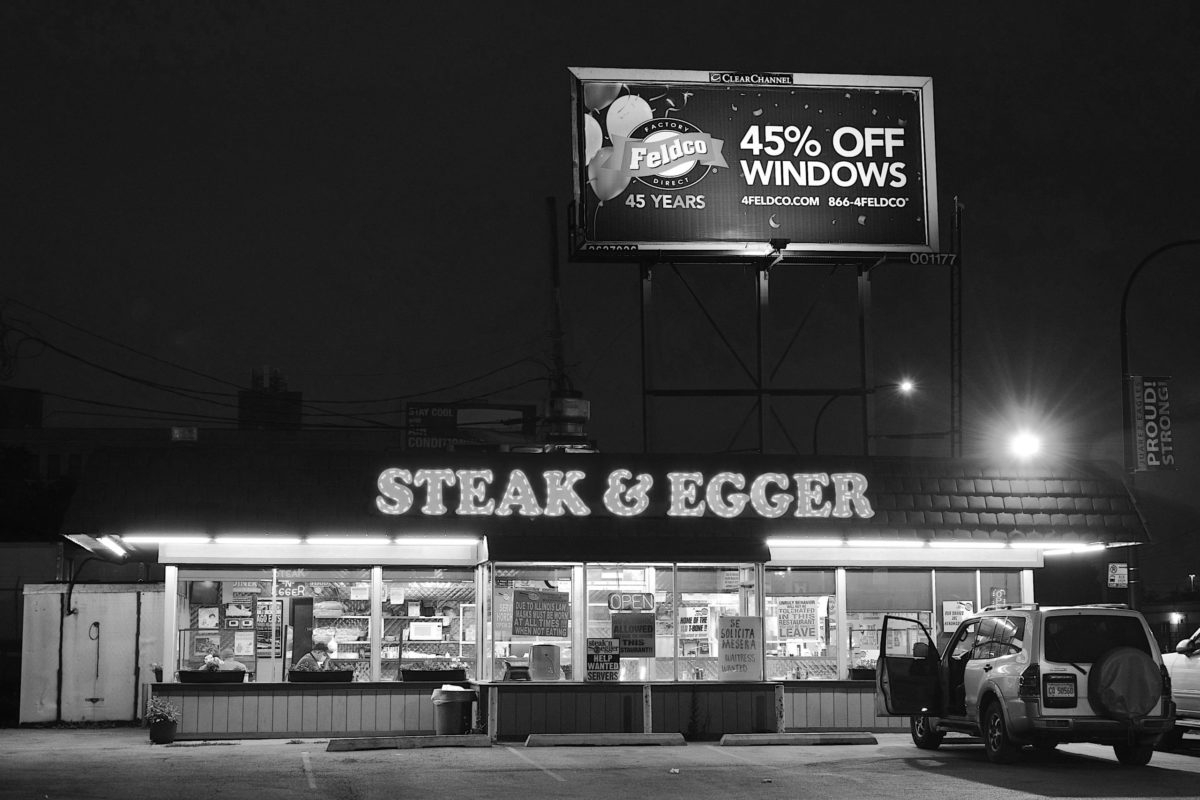

Many of the changes were sad and disturbing. “I saw heavy, heavy gentrification. The process was very clear. When I grew up here you would just have to go to the corner store for your tortillas or whatever. Obviously, there was a bar on every corner, literally like maybe five bars to a street. Those mom-and-pop stores are gone now. A lot of places disappeared, and others are in the process of disappearing. The panaderías, there’s only one left. So I started documenting and photographing these places.

“And eventually I ended up moving from places and buildings to actual people, starting with my neighbors,” she said.

She launched “a little online series” that she called “This is Pilsen during the Pandemic” on Instagram. “I started following a lot of young photographers, Latino photographers, Latinx photographers, from the community,” Solís noted. “I’ve become friends with a lot of them. And I’ve been so enthralled with them and what they’re doing.”

In September, Solís is releasing a book of photography, Luz: Seeing the Space Between Us, featuring some of this work. She fundraised successfully for the book’s publication, and is holding a launch event on September 24 at the National Museum of Mexican Art.

The book is filled with portraits of people and places: the Teloloapan muffler shop, the shuttered Panadería del Refugio, the Steak N Egger diner, Angel’s Tires, teacher Rosalio Mancera, punk musician Martin Sorrondeguy, poet Gregorio Gomez, artist Delilah Salgado, and many more.

The collection “reflects the resilience and complexity of my home community,” Solís said.

The title references the relationships and interactions behind the photographs. “What is it that’s between us, between the photographer and the subject? What happens in that moment? Or what happens when you are communicating with somebody? Oftentimes we don’t see these things, because we’re just not paying attention to them. But there’s so much going on in that supposedly empty space. How do you cross those boundaries?”

Solís is also working with Nicole Marroquín, a professor at the School of the Art Institute, to organize and make accessible some 9,000 negatives from her work in Mexico, Peru, Paris, Spain, Chicago and elsewhere.

Marroquín “helped rescue my archives five years ago from a friend’s basement, where they were stored for over twenty years,” Solís said. “Most have never been seen.”

Solís plans to continue working in digital photography, even though it “doesn’t hold a candle to using film and silver gelatin prints.”

“But at this stage of my life, I’m not going to immerse myself in chemistry anymore. I have a lot of allergies, I battled a lot of cancer,” so working with chemicals in a dark room “is not the healthiest thing for me to do,” she said.

Solís continues to teach photography, including master classes and a program with local women.

“It reminded me of what I did a long time ago, in 1979 when I worked at Mujeres Latinas en Acción,” the Latina social service and empowerment organization. “I was teaching the exact same thing, but with film cameras. We had built the darkroom in the kitchen and the women would come in, take the class in the morning, then develop their film in the evening.”

Now Solís is also in the early stages of a new project documenting the concept of chosen family in Latinx and LGBTQ+ communities, featuring some of the same artists and photographers who have inspired her.

As in the early days, Solís’s work and life are intertwined as she lives and documents the artistic and social movements, and everyday rhythms, of communities in Pilsen and beyond.

“We live the things we do in our artwork and photography,” she said. “You’re just so immersed. Chicago gave me a path to do this kind of work, and that allowed me to go anywhere and do this. It’s been quite a ride. And now it’s like I’m coming full circle.”

Kari Lydersen leads the Social Justice-Investigative specialization in the graduate journalism program at Northwestern University and works as a journalist and author covering energy, politics, and more. She last wrote about bridging Chicago’s food gap during COVID-19.