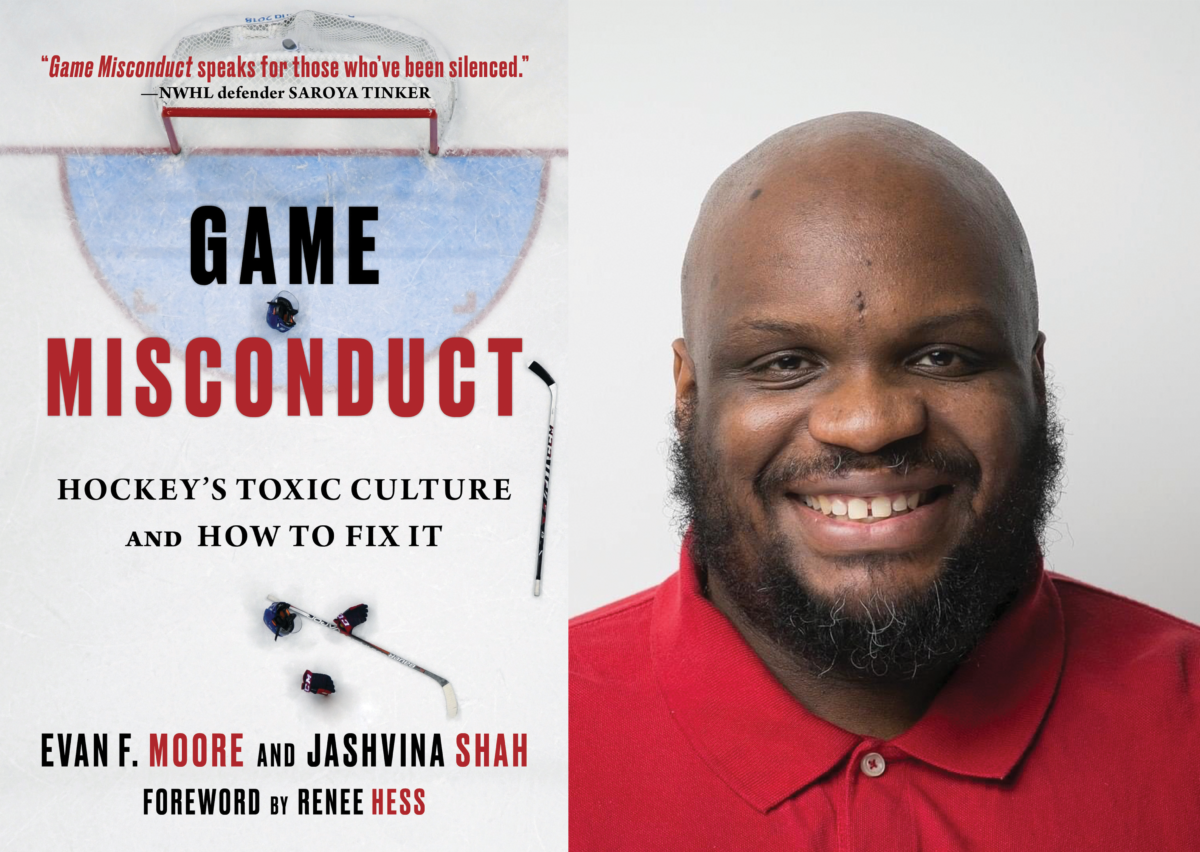

When South Sider Evan Moore first began playing hockey, he rarely encountered other Black players in the rink. Even though he loved the sport, he grew frustrated with social and political issues in hockey culture. Now, as a sports writer, Moore brings his firsthand experiences as a player into a new book, Game Misconduct: Hockey’s Toxic Culture and How to Fix It. Jashvina Shah, the book’s co-author, has had a similarly complicated love affair with the sport, caught at the intersection of hockey and its social issues.

As two of the most prominent critics taking on hockey’s deeply ingrained culture, Moore and Shah decided to band together to write about the sport and offer potential solutions for both hockey at every level.

Game Misconduct is a worthy read for anyone, hockey fan or not. The book lays out hockey’s issues in the broader context of sports solidarity with social justice movements. It is neatly divided into sections that confront racism, sexism, xenophobia, homophobia, transphobia, ableism and more.

While many of hockey’s issues do feel reflective of broader issues in American society, Moore and Shah skillfully elucidate the specificities of hockey as an example of a wealthy, white sport that desperately needs to shed much of its identity in order to grow.

Perhaps the fact that Moore and Shah dedicated so much time and energy to eviscerating hockey culture reveals, as Shah writes, that the sport really should be for everyone. They criticize hockey because they love it, and because they feel that this sport has a potential future to offer so much more than its present. Game Misconduct is a call to arms for anyone who loves hockey, and especially those that have felt hurt, left out, or ignored by the sport.

Evan Moore sat down with the Weekly to discuss Game Misconduct, as well as his relationship with the sport that he not only loves, but would also love to see change.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

I’d love to hear about the beginnings of your relationship with hockey. What is it about hockey that is so compelling to you as a sport?

It’s really fun and dangerous. And there’s a lot of work put in to just even learn how to skate, how to not hurt yourself. I feel like there is science to it, or even poetry. When I saw it as a kid, I saw a really fun and engaging sport. I mean, it caught the eye of a Black kid who grew up on the South Side of Chicago. And it caught the eye of my co-author, a South Asian woman from New Jersey. So we’re both from two different backgrounds, where we would be most likely into other sports based on where we grew up. But somehow, some way, we fell in love with hockey.

How did your and your co-author Jashvina Shah’s identities and experiences with hockey inform one another’s perspectives while you wrote the book together?

That’s a great question, because I was a victim of racism and she was the victim of sexual assault. We both learned a lot from each other. I’m a man who generally believes that he’s as progressive as it comes. But as much as I’m progressive, I think I have some blind spots. I learned a lot from reading her, and she learned a lot from reading what I wrote. For almost a year and a half, most of my text messages and DMs are from her.

What are some of the overarching issues in the hockey world?

Racism, classism, homophobia, sexism, and ableism, to start off.

Do you see any commonalities between those issues in the sport?

Marginalized people in one way, shape, or form are always on the outs. In the book we lay out a case on why that is. We turned in our manuscript in January of this year, and so much has happened in hockey since. A lot of things happened after the book came out. The Blackhawks [sex abuse] scandal, and the Danvers, Massachusetts [high school hazing scandal], and the thing with the girl goaltender [in Pennsylvania] when the crowd was chanting stuff about her. So, these people try to get mad at us and say, “Oh, nothing’s wrong, the sport’s not toxic.” But meanwhile, they’re doing toxic shit.

Could you describe the tradition of ‘billeting’ in hockey? What is it? And how does it impact young players?

In hockey, if you’re really good, you leave home pretty early, and stay with a billet family. A lot of them are in Canada, or in northern states, where there’s hockey towns. Basically you stay with a billet family and play in all these different leagues, which will help you be seen by colleges and also the NHL. And with that, we have all these young kids leaving home way too early and thrown into situations in places and spaces where they may not have the social gravitas to react to it.

With the coaches, it’s way too much power. In the book, we talked to a player who played in one of the junior leagues. And he was smoking weed with his teammates. This was a Black player, and he was the only player kicked off the team. In that sport, the stakeholders, whether it’s coaches, administrators, or other folks, have way too much power over someone’s career.

Why is hockey so expensive?

A lot of first generation Europeans came to the States from places where ice sports were prevalent. And as those generations left the city for the suburbs, those rinks went with. The majority of the rinks in the Chicago area are where there’s wealth, and most of the population is white. We know certain groups may not have the resources or the capital to continue on with this sport. That’s what keeps the sport looking like what it is.

Toxic masculinity seems to underscore a lot of the problems that you identify with hockey culture. Do you see such a cis male-dominated sport ever being on the vanguard of changing that culture of toxic masculinity?

Hockey has long dragged its feet on race and social justice issues. That’s because of their mostly white fan base. Even though all this stuff keeps happening over the years, and these folks always say, “Oh, there’s no place for this in our sport,” it’s ongoing. And it’s been there for a long time. You know, why don’t you lean into figuring out what’s really going on? Because the NHL has had diversity efforts since 1994, but yet these incidents happen all the time.

The Blackhawks scandal has really shone a light for the broader public on some of the ugly truths about hockey culture that you cover in your book. What was your reaction to the scandal when it broke?

I wasn’t shocked. For me, reading the report and seeing that interview [with Kyle Beach], the first thing I said to myself was, if they’re covering for a video coach and providing services for a video coach—what length will they go for players?

How would you respond to people in the fan base or in the organizing structure of the NHL who say that these issues are political, and sports offer an escape from issues such as these?

Sports is politics. They coincide, they exist together. Why is your favorite rink named after a corporation? There’s people out there who want to stick their head in the sand when they say, “Stick to sports.” There’s so much hypocrisy out there. At this point, someone who thinks that way is being willfully ignorant. They’re making a conscious choice to ignore centuries of history. And that’s on them.

You saw that locally, with the Blackhawks and what was laid out. And you still have people out there who have a hard time understanding the power dynamic, where a hockey player was told by a coach, “Go along with this experience or you’re not going to play hockey.” Knowing hockey culture, where these players’ only goal in life is to make it to the NHL and make it to professional hockey. When you have that singular focus, unfortunately, you may be susceptible to going along with things that are otherwise awful.

What do you think comes next for the NHL?

I mean, they’ve already made provisions not to change. So we’ve got to keep pressure on them, and keep pressure on their corporate sponsors. Even though we got the desired outcome, the league allowed them to run their own investigation. That should have been taken out of their hands and given to an independent group.

If you could speak to the Danvers school administration, parents, and that hockey team, what would you want them to hear?

I feel like these behaviors are learned. So they saw it or heard it somewhere, whether it was at home or at the rink or in school. And it goes into what we see in terms of sexual assault, or racism and homophobia — all this stuff is learned behavior. It’s hard because of how young they are, and how resolute in what they were saying and doing. And it’s like, is this just how somebody is? Or is there still time for them to change their behaviors? And I will say to administrators and parents, this is on you. Step up, and tell your kid to cut the shit. If you don’t, you’re training the next generation of people who probably were at the Capitol on January 6th.

Your young daughter plays hockey. What does she love about hockey, and what do you love about seeing her play this sport?

I didn’t necessarily try to push her into the sport. But I got wind of a girl’s hockey class that was hosted at the Blackhawks rink. And she loves it. There are times where I’m in the house, shooting the puck or whatever, and she’ll be like, “Dad, why are you doing this without me? What the hell?” And now it transitioned to: “Are we playing hockey today? I love hockey, let’s go play hockey!”

As she progresses in the sport, obviously I think about some of the stuff that we describe in the book. I moved up the timetable for me and her mom to speak to her about race, because she’s one of the few melanated kids out there. So I’ve had a conversation with her: “If someone says something to you or makes you feel uncomfortable, you grab me or grab your mom or talk to a coach.” Because in the book I discuss how I was called a racist word by a teammate and I handled it internally, away from coaches and everything else, because at that age I already knew that I was going to be on my own with this. But I don’t want her to internalize that experience, you know? I bought her a Barbie doll set where one is a white player and one is a Black player. She turned six a few weeks ago, and she already is aware of who she is. I have a video of her opening up the dolls. She ran to me and gave me the hardest hug I think she’s ever given me. And she says, “This girl plays hockey like me.”

What groups and individuals are you seeing work to counteract specific issues in the hockey world?

Oh, you got Black Girl Hockey Club with R. Renee Hess, the founder and executive director. She actually wrote the foreword for our book. And that group started because she heard of a bunch of Black women and other allies who wanted to go to hockey games, and they felt like, “Hey, we ought to get a group together and go together. There’s strength in numbers if we do that.” They transitioned from that to raising money and providing scholarships for young Black girls to play the sport. You have different groups all over, but since this is the South Side Weekly, I’ll keep it local: Hockey On Your Block, Inner-City Education, and Chicago North Stars, which is an all-women’s team that plays in the men’s league. All these different people have different entryways into the sport, and they see the way things are broken. So they feel like, “We have to do things our way.”

Do you feel optimistic about the future of hockey?

I’m more optimistic than I thought. I look at it like, we’re not going anywhere. I remember when I first wrote about being a Black hockey fan, and I heard from so many people. Black folks that were like, “I feel seen. Thank you for writing about our experience.” So, as more people get into it, and feel comfortable, the face of the game will change.

Game Misconduct: Hockey’s Toxic Culture and How to Fix It, by Evan Moore and Jashvina Shah. 256 Pages. Triumph Books, 2021. $28 hardcover.

Sage Behr is an actor, writer, and barista, originally from Iowa City. She last reviewed Gabriel Bump’s novel Everywhere You Don’t Belong.