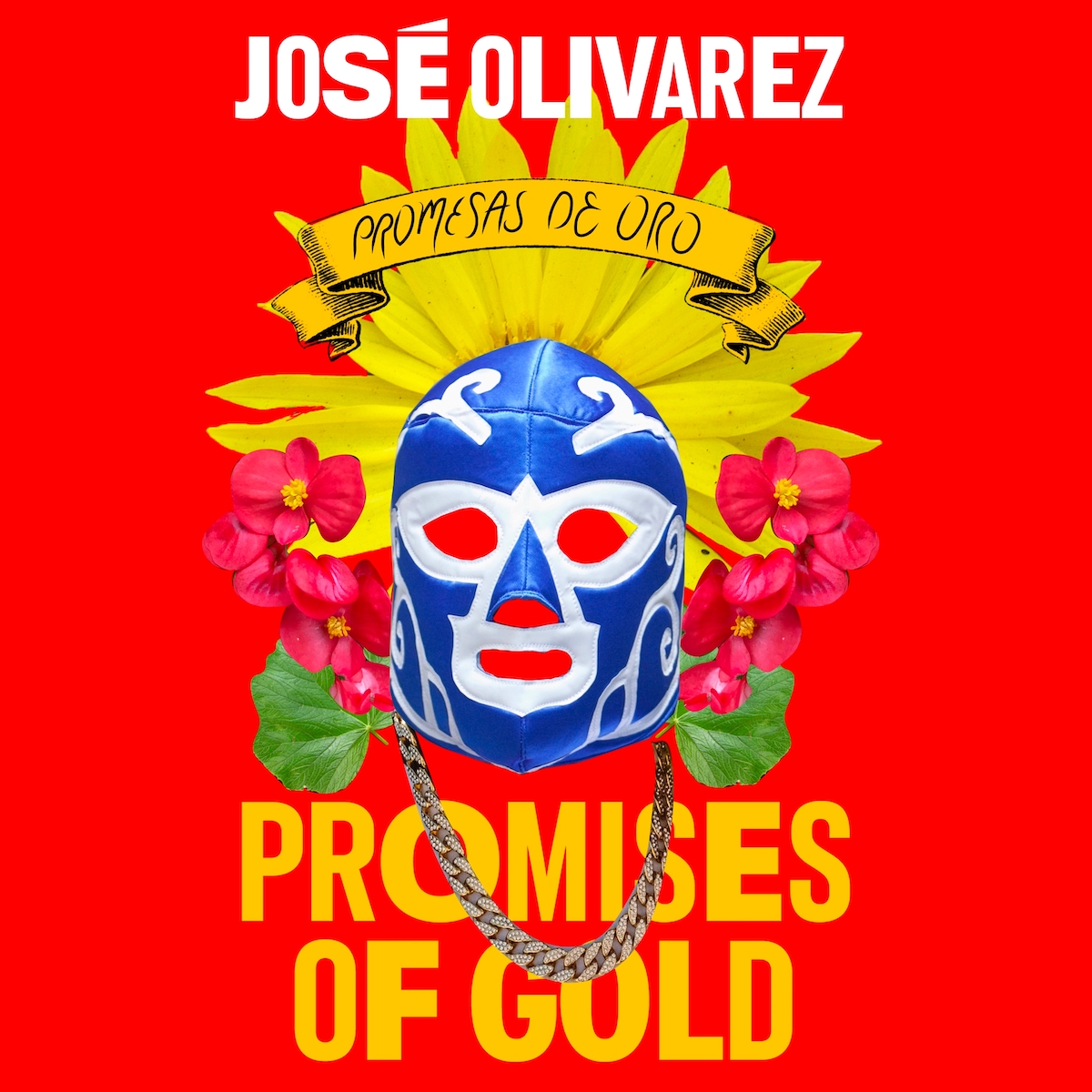

José Olivarez’s latest poetry collection, Promises of Gold, is “a book of love poems for the homies,” written amid a global pandemic that has left us raw and exposed to all the other forces that we constantly live through every day. Published this February, Olivarez celebrates love in all forms—familial, fraternal, and sometimes fleeting.

Originally from Calumet City, Olivarez is a poet, educator, and performer. His first poetry collection Citizen Illegal explored themes of immigrant identity, family, politics, and Chicago nostalgia. After its success, Olivarez released Promises of Gold while wrestling with the legacy of colonialism and capitalism and how to keep love alive.

Olivarez began writing Promises of Gold in 2019, with some of the book’s earlier poems published as early as 2013. The collection’s title and its chapter names call back to the shorthand of “Gold, God, and Glory” which spurred Spanish colonizers toward extraction, eradication, and enslavement in Mexico and Spain’s new imperial conquests.

In Promises of Gold, Olivarez stylistically draws on Spanish colonial imagery and the language of empire for the book’s structure, but he also uses them to echo the process of undoing colonial harm. “What is gold to us? What is holy to us? Where do we find glory?” Olivarez asks us in the forward of his latest collection.

Promises of Gold is a post-pandemic collection through and through—filled with class anxieties and righteous resentment toward the rich and powerful. In one of his poems,“It’s Only Day Whatever of the Quarantine & I’m Already Daydreaming About Robbing Rich People,” Olivarez fantasizes about punching Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos in the face and living long enough to punch him again.

“I think it resists empire by resisting the way that empire wants to make all books functional,” Olivarez said in an interview with the Weekly. “It’s not an anti-racist book…it doesn’t have a diversity, equity, inclusion type of purpose. It’s useful, maybe only for those of us that are interested in organizing.”

Many of Promises of Gold’s more economically-stressed poems stem from wanting to be more direct about class. “When I wrote Citizen Illegal, I thought class identity was a big part of those poems. And I found that…mostly the conversations that people were interested in having with me were about identity, belonging, and family,” Olivarez said.

In writing these poems, Olivarez wanted to capture the way class and financial insecurity have shaped his own life. There is a blunt anger spinning through the pages—from the promise of upward mobility, what the rich do to be paid first, and learning how to adjust to having money but always feeling the anxiety of money problems.

“I was talking with a friend the other day, and I was like, ‘there’s not a day that goes by that I don’t feel stressed out, looking at my bank account. It doesn’t matter how much money I have. I don’t know [if] that kind of insecurity will ever go away,” Olivarez said.

Laid throughout Promises of Gold is an attempt to understand how artists make art that resists empire, but they can also be absorbed within empire—critique, commentary, and all. “American Tragedy” puts this front and center:

“…it is easier to listen to an artist outside detention capable of

spinning the secret into a coin, we can share at a dinner party where everyone will sigh & look

contemplatively that’s their part in this american tragedy”

Following that, “Poem with a Little Less Aggression” characterizes audiences and the state as implicit in the violence and consumption of capitalism, even the artist who clarifies before his critique, “when i am invited/ to the halls of wealth…i take my seat/ i snap a flick/ i pose with all my teeth showing/ how harmless/ i am.”

“…i can’t help the poor if i’m one of them says the billionaire. i can’t help the poor if i’m one of

them says the banker signing off on my family’s foreclosure. it’s true, you know: there is no ethical

consumption under capitalism. some truths are useless.”

“Having been a little bit more celebrated by different poetry and cultural institutions, just seeing how those organizations and those institutions can champion a certain type of political stance, [but] at the same time, they can turn around and accept donations and money from the grossest people on the planet,” Olivarez added.

“Part of what I’m trying to do is just remain vigilant and maybe even suspicious of myself in some ways, trying to stay grounded in remembering that all of that stuff is transient. What matters is not necessarily that type of institutional support, but writing poems in community with people that are struggling against empire is a way that I would phrase it.”

In his author’s foreword and while talking to him, Olivarez often refers to his poems as attempts—to make beauty out of a situation or create space for imagining something different. “Some poems are failed attempts in a way. They can’t actually undo the harm they’re trying to undo. They can’t actually rescue the moment they’re attempting to illustrate or show or reveal.” There is a tension in making the ugly and complicated, beautiful, but Olivarez thinks of writing as attempts to hold the temporary nature of these moments and let them live longer.

“I write a lot about family and about possible lives of family members…and I write a lot about my family who has passed away. In some ways, the poems are most beautiful to me when they can hold those people,” Olivarez said. “It’s this imaginary space that I create in the poems, and at the end of the poem, those spaces disappear into the ether. To me, the beauty continues to exist even when they do fold up into the ether because it makes it so that I can continue the conversation just a little bit longer.”

In the poem, “An Almost Sonnet for My Mom’s Almost Life,” Olivarez crafts a life that could have been for his mother had she not had children.

“…she spends her twenties following Marco Antonio Solís show

to show. hands up in surrender. in praise to a different god

than the one she spends Sundays kneeling to now i love imagining

Her like this: her name Maria, Maria a name the men curse

To the heavens from Guadalajara to Oaxaca. the holy name of the mother

reborn a mother to none..”

In this almost-alternate reality, she chases musician shows and takes care of only herself. The poem remarks she would protest if she heard this, but it keeps wondering what her life would be like with a life all her own. In writing, Olivarez fills in the gaps of silence between himself and aspects of his mother that he simply cannot know.

“One of the big revelations for me is, my parents growing up would talk to me about

the sacrifices they made for me and my siblings, which made me think that they always carried some amount of sadness, or longing for the life that they left,” Olivarez said. “But my mom always made sure to tell me, ‘I’m not sad about the choices that I’ve made. This is my life. And this is the life that I wanted, and I chose it.’ In that same poem, there’s this point where she pushes back in [and] says that her life would be boring without family and without God, which is how my mum would really…that’s like what she says.”

Throughout the collection, Olivarez navigates loneliness, wistfulness, and heartbreak in ways both tangible and new. “Poetry Is Not Therapy,” as he titles one poem, yet its first line answers, “but that doesn’t mean i didn’t try it.”

But Promises of Gold is filled with tongue-in-cheek humor, much of which comes from how Olivarez writes. Olivarez starts by imagining his three younger brothers and writing a poem they would like. “It’s important to me that they don’t feel excluded from the poems, that if they want to read them, they can,” he said.

While emotional and heavy, the book shines at its most when it’s wavering between silly and sincere, earnest and amusing. In public readings, audiences are between laughter and still silence. “I think humor adds a very particular texture to poetry that is useful. It can help give it some spark and fire and animate them in a way,” he said.

In Promises of Gold, the lyrical comes to life in the everyday—whether the reader is laughing alone with the book or listening to his spoken word in a crowd. His favorite poem from the collection is “Eating Taco Bell with Mexicans,” whereupon introducing his future wife to his brother and promising to take her to a secret Mexican food spot, they take her to Taco Bell. The collection occasionally features his brother’s quippy text messages about becoming “MIDDLE CLASS in this mf” and how the sky and poetry are dope.

Promises of Gold went to print simultaneously with its Spanish translation by David Ruano González, a Mexican poet and translator in Mexico City. González’s translator’s note is found at the beginning of the book.

If an act of translation is always an act of betrayal, as the common saying goes, González adds that “translation is a decision too.” His commentary in the collection explains some of his decisions and how he negotiates meaning, rhythm, and wordplay between Olivarez work and his own. Gonzalez navigates between being as true as possible to Olivarez’s intentions and to the Spanish language. As he puts it, the second half of Promises of Gold is “the experiences of a Mexican from Chicago turned into the Spanish of a Mexicano who lives in Mexico.”

For Olivarez, reading his poetry in his first language makes them feel new again. “Even though I know in English what happened, seeing how the poems unfold in Spanish still surprises me and makes me emotional and makes me feel like I’m outside my poems in a way that I don’t know,” Olivarez said. “Spanish was my first language, and it’s the language that my family uses to talk to each other, so to see some of those memories, which I’ve only processed in English, borne out in the language that they sometimes happened, it made them feel a little bit raw.”

The “Mexican Heaven” poems, which feature so prominently in Citizen Illegal, are here again. In Citizen Illegal, the poems are a running thread which call back to each other and all anachronistically depict heaven and its familiar faces. There are no white people in heaven. Jesus is your reincarnated cousin from the block and God is “one of those religious Mexicans” with whom the others avoid drinking or smoking around. Sometimes, people are welcomed at the gates, and sometimes, Mexicans must sneak in or work in the kitchens to achieve their own version of the American dream.”

Citizen Illegal makes no attempt to promise the American dream. But in Promises of Gold, these Mexican heaven poems take on a darker tone. Scattered three times throughout the collection, each poem rejects heaven and all it has to offer. For its people, heaven has lost its luster.

The Mexicans say “no thank you to heaven,” because a paradise would require someone to clean it. Its inhabitants find its fancy parties boring, text each other that it is time to leave, and ditch paradise for a better spot in between heaven and hell. In the second “Mexican Heaven” poem, Olivarez writes:

“forget heaven & its promises of gold—

everything we make on this planet

has one purpose. every poem, every act

of photosynthesis, every protest. if heaven

is real, then its gates are closed to us. maybe

heaven is just a museum of all the life

we have extincted…”

Later in the poem, he adds:

“…in death, we arrive

at god’s house—only to find god torturing dolls.

we wanted to be made in god’s image—we imagined

gold & not the melting that gold requires.”

In his own words, Promises of Gold “attempts to make beautiful the complicated, but does not ignore the complicated. It embraces the world.”

Reema Saleh is a journalist and graduate student at the University of Chicago studying public policy. She last wrote about the changing of the guard in City Council.