Fifteen years ago, when Mack Julion first came to Saint Sabina’s in Auburn Gresham, the church didn’t have a youth ministry. After working for a few years in the office of the church’s longtime pastor, Father Michael Pfleger, he managed to convince Pfleger to let him start one. Now, the church’s youth ministry has programs for parishioners from ages thirteen to thirty-five. In some ways, Julion is a perfect Saint Sabina’s success story: the church empowered him to empower others.

Julion looks and sounds younger than he is. In addition to his current work in the church’s high school ministry, he teaches at a Noble network charter school and writes spoken word poetry in his spare time. He believes that knowledge of Scripture is crucial for teenagers from underserved neighborhoods: it helps them build a moral foundation they might not get anywhere else.

“With teenagers, it’s always about peer pressure,” he says. “The Scripture just allows them to know that you’re not of this world. Just giving them that is very important.”

Young people are not well represented at Saint Sabina’s on Sunday mornings. The few who do come to services sit in the rear pews to the left of the altar, near Julion. But for Saint Sabina’s, this demographic is nothing short of precious. After sermons, Pfleger huddles with the young men in attendance, and sends each of them away with a hug. Through ministry, Saint Sabina’s hopes to bring young people into the church before they make bad decisions.

But though it may be empowering, youth ministry is also self-selecting. Not all young people who are involved with violence and crime can be turned around through preaching and evangelism. As a result, Saint Sabina’s has resorted to other, more publicized methods to engage South Side residents young and old—marches, demonstrations, monetary rewards for guns turned in and information about shootings. But Julion says that despite its good intentions, this work is often too little, too late.

“We hear that a child got shot and killed, we march,” he says. “That’s reactionary. There’s not much we can do beforehand other than provide the resources that we have.”

Saint Sabina’s and Pfleger especially are famous in Chicago not just because they have spent forty years fighting to improve quality of life in Auburn Gresham, but because many think they have succeeded. The church’s work in the neighborhood has been described by admirers ranging from the Sun-Times’ Carol Marin to President Barack Obama as “heroic,” “transformative,” and as the “lifeblood” of the community. But after decades spent working for change within the neighborhood, Saint Sabina’s has taken up larger, more complex battles. The church now focuses its local outreach and intervention on the same systemic issues that have made Chicago the object of national attention—gun violence, unemployment, and disinvestment. Many members of the church admit that these battles often seem impossible to win: although the church is a fundraising powerhouse, with dozens of programs, services, and ministries, it deals with inequality and abandonment that extend beyond Auburn Gresham. Moreover, the church exists in a state that has gutted funding for social services and a city that seems unwilling or unable to address the crises facing its black neighborhoods.

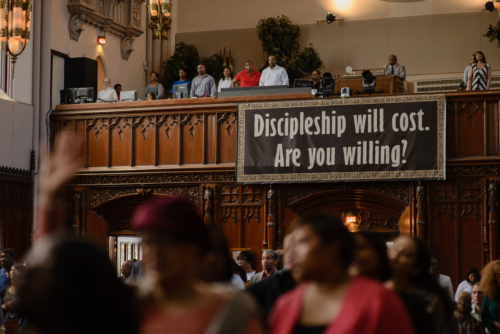

But Saint Sabina’s has only fought harder as the outlook has gotten worse, because what keeps Pfleger and the church’s leaders wading upstream isn’t just the belief that they’re doing the right thing. They also believe that no matter how bad things look, a higher power has ensured their victory from the start. Governments and charities might see social change as a matter of policy, but the church sees it as one of destiny; in other words, even if they can’t win, they have to keep fighting.

Saint Sabina’s was founded one hundred years ago this July, when Auburn Gresham was still a predominantly white neighborhood. Pfleger first came to the church in 1975, when white flight had brought its membership down to fewer than fifty people—today, an average Sunday at the church draws several hundred. For much of the 1980s and 1990s, the church worked to restore the 79th Street commercial corridor and revitalize its immediate surroundings. The congregation first drove drug dealers away from 79th Street, then forced local gas stations and stores to stop selling drug paraphernalia and warded off an influx of tobacco- and alcohol-themed billboards from the neighborhood. Later, parishioners fought to root out prostitution on 79th and in Auburn Gresham at large, buying time from prostitutes and using it to try to convince them to change their ways.

As the church has gradually restored its surroundings, it has expanded into a compound of stores, goods, offices, services, and living facilities. The cathedral stands on 78th Place and Racine, but there are buildings owned by or affiliated with the church in every direction, including a K–8 school, a senior living facility, and centers for employment, social aid, and neighborhood development. The church has lobbied to bring businesses to the neighborhood, including a BJ’s Market & Bakery, a Wal-Mart Neighborhood Market, an Osco drug store, and a combination Walgreen’s–Chase Bank that stands on the former site of a by-the-hour motel that prostitutes would frequent.

But in September of last year Pfleger wrote an op-ed in the Tribune in which he argued that Auburn Gresham still faces the same problems it faced when he first moved to the neighborhood, and that, if anything, things have gotten worse since then.

“Three decades ago I saw this South Side community struggle with poor schools, high unemployment rates, violence, drugs, and the availability of few business opportunities,” he wrote. “What’s painful today as I walk down the same streets is that things seem to be getting worse. I see more boarded up homes and vacant lots. More people who have been in prison aren’t given any options or job opportunities…Poverty remains on the rise.” The summer of 2015, Pfleger wrote, was the most difficult Auburn Gresham had ever seen.

The “destitution” Pfleger wrote about has come about because of forces that are well beyond any church’s power to influence, much less overcome. All of the trends that parishioners say have dragged the neighborhood down have been decades in the making. Furthermore, the timeline for recovery isn’t really in the neighborhood’s control: in the early 2000s many South Side neighborhoods had begun to recover, but the 2008 housing crisis brought things back to square one. When I started attending services at Saint Sabina’s earlier this year, Ribs Unlimited, a black-owned restaurant that has been on 79th and Loomis for decades, had recently shut its doors. Hinton Heating, a black-owned business on 79th and Sangamon, was planning to close as well.

Saint Sabina’s has picked different battles over the years, but its methods have been constant: in past decades, parishioners held demonstrations against drug dealing and campaigned for new businesses to come to the neighborhood; today, they hold marches against gun violence and demand increased investment in education and job creation.

Ministers and parishioners alike will be quick to tell you that the church’s commitment to social action comes directly from Pfleger, who combines Catholic teaching with the philosophy of his idol, Martin Luther King, Jr. According to parishioners like Norma Bradley, who have attended the church since before Pfleger was pastor, Pfleger also taught the congregation to tithe. Members of Saint Sabina’s are all asked to tithe ten percent of their income in order to help the church raise $30,000 each week.

For decades, local and national media outlets have made such a myth out of the priest that an outsider might think he had done all the work himself. To be fair, he is a compelling figure: a white priest beloved by a black congregation, a Catholic who learned to preach from storefront Baptists and locked horns with the Archbishop. As early as 1989 he was the subject of a lengthy feature in the Reader whose subtitle was, “What’s a white boy like Mike Pfleger doing in a parish like this?” The author of that feature went on to write a book about Pfleger, Radical Disciple, which became the namesake of a glowing 2009 documentary. Earlier this year, Evan Osnos of The New Yorker wrote an 8,000-word profile of Pfleger; the article did not quote anyone else from Saint Sabina’s.

But Pfleger says he’s never set the agenda for the church’s work in the neighborhood—that, from the beginning, he merely helped the parishioners take a stand and make their voices heard. But even as the church and the scope of its social work have grown, the immense need for this work seems to have outpaced that growth.

“If we had churches that operated like [Saint Sabina’s],” says Julion, “then we’d see communities begin to change. From 78th to 87th, if we just went down Racine, there’s a ton of churches…if every church operated to help members of the community, this whole stretch would change.”

With over two hundred murders logged so far this year, 2016 is on track to be Chicago’s bloodiest year since the 1990s. Much like what Pfleger wrote about last summer, the consensus among parishioners is that this summer will be the hardest in recent memory.

The church’s efforts to fight this violence are all based on the idea that it can convince gang members to stop shooting by intervening in their conflicts or by showing them the extent of the damage they’re causing. The church employs full-time “peacemakers” who actively work to diffuse gang tensions, and holds a “Peace League” on Monday nights, offering young men a safe place to play basketball. A monument was built recently in the church’s courtyard bearing the photos of young people whose lives have been lost to gun violence. Entitled “Our Angels, You Are Not Forgotten,” the monument stares out at passersby on Racine.

These programs and demonstrations might not all seem “reactionary,” but none of them address the root causes that produce gang wars and gun violence in the first place. Pfleger knows his routine tirades against shootings and homicides are meaningless if society can’t provide gang members and drug dealers with jobs and opportunities.

This reality became apparent earlier this year after the death of Phillip Dupree, an ex-gang member who had recently started attending services at Saint Sabina’s when he and his grandmother were shot while driving, a half-mile away from the church. At Dupree’s funeral, Pfleger asked for any young men who wanted to turn their lives around to come up to the altar. Nearly one hundred and fifty men stepped forward. Saint Sabina’s might have enough resources to enroll these men in GED classes, but not enough to find them all jobs, or even to guarantee them all bus cards.

In the absence of systemic change, the church’s anti-violence work can feel like a case of one step forward, two steps back—one of the church’s peacemakers was shot last year while in what Pfleger described as “somebody’s so-called territory.” But the church’s fight against the economic conditions that produce this violence is even more of an uphill battle than its fight against the violence itself.

The statistics on unemployment, for example, are staggering: a Chicago Reporter analysis of 2013 census numbers showed that twenty-five percent of African Americans in Chicago were unemployed. Among young people, the problem is particularly dire: earlier this year a report from the University of Illinois at Chicago found that forty-seven percent of young black men in Chicago were unemployed; the jobless rate for residents of Auburn Gresham aged twenty to twenty-four was 61.3 percent.

In the midst of these numbers stands Lisa Ramsey, the director of the church’s Employment Resource Center (ERC). Ramsey has been attending Saint Sabina’s for twenty years; she started working for the church full-time after a career at Kraft Foods. When we spoke in the church’s basement, she stopped a few times during our conversation to talk to a teenage girl who is staying with her for a week while she doesn’t have a place to sleep.

The ERC was founded in 1998 with the initial goal of ensuring that the new jobs that were being brought to the neighborhood went to people who actually lived there. Today it offers a list of services so long that Ramsey cannot list them all in one breath. Mainly, though, ERC staffers offer employment counseling to about five thousand people per year, less than five percent of whom are members of Saint Sabina’s.

At every stage of the counseling process, the ERC has to contend with the inequity and neglect that have shaped communities like Auburn Gresham. The ERC works in the opposite of a vacuum: it can’t provide counseling or services without understanding the forces that have influenced a person’s entire life. And in Ramsey’s view, unemployment causes as much spiritual hardship as it does economic hardship: just as Pfleger and the peacemakers try to fight gun violence by appealing to gang members’ souls, the ERC has to try not only to connect residents with job opportunities, but also to help them turn their lives around.

“When those people walk in the door, you have to understand that they feel like crap,” she says. “A lot of these young men, all they want is someone to tell them that they see them. Just acknowledge that they’re an individual and they’re a human being and they have value.”

But as funding goes down and unemployment rates go up, such deep engagement becomes harder: the ERC’s funding was cut this past year, which brought its full-time staff down from twelve members to six. It has had to shift from individual counseling sessions to group sessions of up to thirty people.

“You can always have someone sitting in an office, but the need is so wide, so broad, and our young people, they don’t have skills,” says Ramsey. “If you come on the South and West Sides and look at the schools, there’s a huge disparity in the learning, and the ability to learn…the need seems to be increasing, not decreasing.”

When discouraged by these numbers, some church leaders take a cue from Pfleger’s legendary dedication to serving his community. Ramsey, for example, says he’s the only boss she’s ever had who works harder than she does. But parishioners and ministers say that what ultimately keeps them fighting isn’t admiration for Pfleger, but faith—“the substance of things hoped for, the evidence of things not seen.” It’s this faith that drives Saint Sabina’s to fight in exactly the places where it seems the church is least able to make a dent.

“You can’t get tired,” Ramsey says, “because somebody is sleeping in the car tonight, somebody is contemplating suicide because they can’t feed their child, somebody is ducking because they don’t want to get shot…most times I feel like I’m not doing enough.”

As Deacon Richardson tells it, Saint Sabina’s is unique in its ability to look past the ever-changing numbers on poverty and violence, instead choosing to focus on what he calls the “bigger picture.” The church keeps up what looks like an impossible fight because its ministers and employees share an essentially Christian belief: in the end, good wins—or as Pfleger wrote on Facebook the morning of Easter Sunday, “THE FIGHT IS FIXED!”

Saying that faith is essential to a church’s work might seem far too obvious, but it’s worth considering whether Saint Sabina’s could do everything that it does if its leaders didn’t believe in the certainty of their victory. Pfleger, for his part, says that if he weren’t a Christian he would have walked away long ago, and he doesn’t see how it could be different for anyone else. He points to the faith of Martin Luther King, Jr., who also believed in a victory that he never lived to see.

“I believe the arc of justice is bent toward us,” he told me one morning, having just returned the previous day from a trip to the White House. “Light overcomes darkness. That’s my faith. So I’m a prisoner of hope because of that. But it’s not about whether I see it.” A poster in the lower level of the church shows a much younger Pfleger holding a Bible and flanked by angels. The poster reads, “BUILDING AN END TIME CHURCH FOR A NEW MILLENNIUM.”

Pfleger is three years shy of seventy, the recommended retirement age for priests in the Catholic Church. It’s not certain that he will retire once he gets there—after all, priests are also supposed to change parishes after six years. But if it really is faith that drives Saint Sabina’s, and not Pfleger’s charisma or clout, then the church has nothing to worry about. Pfleger himself designates younger ministers like Julion as the church’s next generation of leaders. He believes this next generation shares his certainty that good will win, and will keep that certainty despite any and all evidence to the contrary.

At the height of his sermons, however, one might think that the deliverance he describes is right around the corner. The futility that the church’s ministers and social workers face on a daily basis seems to drop away. Standing in the Gothic church, surrounded by fake plants and woodcarvings, Pfleger returns again and again to a promise that always makes the congregation stand and shout: the Lord will provide, and he will provide soon.

“Put up your hands and say, peace in Auburn Gresham!” he roared on a recent Sunday. “Peace in Englewood! Peace in Lawndale! Peace! Peace! Peace!”

I lived in St. Sabina’s, back in the 50’s, went to grade school there, came back in H.S. { Br. Rice }, to attend the Sunday evening dancing & fighting sessions. Later, i worked with S.C.L.C. & sncc. I was able to meet & shake hands with Dr. MLK, in a Baptist Church, on 71st. { a Peak Experience in my life } I have the Greatest Admiration for those, who have stayed & continue to fight the ” Good Fight ” in good old St. Sabina’s. More Power to YOU !

I still believe in miracles!

We read about Father Pfleger now, but we knew him then — when he was a new Christian starting out on the Westside. He was just “Mike” working as part of a team of folks who didn’t need a Ph.D. to love the Lord and love a third grader. That love: allowed me to drink a whole can of pop when I always had to split a can at home – if we had a can at home – with my four siblings; taught me the words and rhythm to the Black National Anthem; took me to the Wisconsin Dells – the first and only time until my twenties that I could leave the big city; developed confidence in me and, with it, this crazy notion that I could compete in predominately white schools; and showed my single and afraid mother that she was not alone.

I reintroduced myself to Father Pfleger a few years ago and I only had to say my family name when he blurted out “I remember your brothers Sam and Donald”. After forty years? I cried most of the way back home — a 552 mile drive.

Yes, Father Pfleger acts “crazy and loud” at times, but he didn’t out-crazy or out-loud the love that called him to serve his entire life and that he continues to give — and give not without great risk. Keep doing what you’re doing Father Mike. You, as you always have, and your team are making a real difference in somebody’s life. In God’s Name.

Very interesting article. I belong to a Catholic church in Philadelphia and my pastor is similar to Dr. Pfleger.

I have been attending service at St.Sabina’s for five months.

The mass is lovely, congregation devoted, and Fr.Pfleger inspirational. There is Love in the in the Air…Let’s hope he right “The fight is fixed!”

Elayne. The service may be great and inspirational and that’s fine, and Lord knows we all need more of that in the world today, but here’s the thing. But that’s simply a temporary relief from what’s really wrong. People have to come together as a community and take their neighborhoods and their lives back in order for any real change can take place. The first thing you need is a clear CODE OF CONDUCT. What type of behavior do we allow in our community? What is the standard? What value system do we live our lives by? What business are we handling or not handling and what is the result thereof? These are the questions that need real answers. And there’s another thing that people don’t understand. No one is going to ever invest in you if you don’t invest in yourself. Help comes from helping yourself. Not everyone wants help, not everyone wants to be saved or rescued. Most of these knuckleheads don’t wanna hear shit from nobody. They ain’t listening to nobody. And we can’t waste time and energy with people who don’t wanna do anything, that’s nonsense. Everybody black I know is doing their thing and living life, some of them are living it up, something serious. People need to take personal responsibility for their own lives and stop expecting someone else or society to take care of them and make sure they’re okay. No, it’s your responsibility to make sure your okay. It’s your responsibility to have a job, it’s your responsibility to make sure you have an education, it’s your responsibility to have marketable skill sets, it’s your responsibility to have your own money to pay your way around town, that’s your responsibility as an adult to do whatcha need to do in life. Ain’t nobody responsible for taking care of grown-ass people, people need to get off this entitlement shit. The world don’t owe you shit, get off ya ass and get it your cha GOD DAMN SELF.

St Sabina and Father Mike have done an excellent job of cleaning up the area and making it a decent and respectable place to live. The neighborhood is fairly middle class and the neighborhood has experienced vast improvements from what it once was. But there is still a lot more work to do. They’ve reduced violence significantly but nonetheless there is still a lot of unemployment and poverty in Auburn Gresham. The Employment Resource Center can only get so many people jobs. Cause the need to so great and it’s a need that’s growing everyday. Getting rid of the cigarette and liquor ads along with the drug paraphernalia and dope traffic has gone a long way with turning the neighborhood around. They’ve brought some mainstream businesses to the neighborhood and got a lot of folks back on their feet. But as the recession hit and people fell upon hard times, things have gotten rough. But I stilk commend them for the awesome work they’ve done in Auburn Gresham and in Chicago as a whole. I totally love and respect Father Mike. He’s a thorough dude. A man after my own heart. Most of the churches in Chicago ain’t doing nothing and cant effect no change worth talking about. They cannot. If they could Chicago wouldn’t be helter skelter like it is now. But big ups to Father Mike and St Sabina. Keep up the good work Family.

I’m puzzled here..Cause when I look at the Pillars of Auburn Gresham and other videos on YouTube like the Havens of Auburn Gresham, it seems like St Sabina has really turned that neighborhood around for the better. But even in the video The Pillars of Auburn Gresham, Father Mike is honest and truthful about where the neighborhood was when he first got there and where it is now. Parts of Auburn Gresham are still bad and many struggles remain. But it looks like Father Mike and St Sabina has done an awesome job. I think Father Mike and St Sabina should bring in some financiers who know how to make money grow so that St Sabina is always flush with cash regardless of what happens. That will go a long way in solving the poverty and unemployment problems and revitalize not only Auburn Gresham, but most of Chicago, especially black Chicago.

Unemployment causes as much spiritual hardship as it does economic hardship. In fact, the spiritual hardship is actually worse the economic hardship. I remember times that I was out of work for like 6 months straight and that was the worst and most torturous time of my life and the countless times I got fired from jobs, I felt so low about myself. Losing a job or being unable to find one is a lot more painful than being broke. It leaves you not only financially broke but feeling broken, feeling like a loser and feeling useless that your life has no purpose. It’s a deep dark depression in your spirit. It can make you wanna die but I ain’t never wanted to kill myself, hell no. But none of that is a reason to kill yourself or someone else cause things in life happen to everyone, we all have low points in life. Under no circumstances will I go them routes. You just got to be proactive with your life and do whatever it takes to get your life together. With a strong spiritual foundation and a solid work ethic you rise above any adversity and achieve success in life.

People got to want better for themselves. About jobs, believe it or not, you can create your own job. Barbering, Hair dressing, cook food, bake cookies and sell it, mow lawns, plant a garden and grow food and sell that shit on Facebook. Better yet. You can even run your mobile detail car wash business. I’ve known tons of black men who’ve done this. I used to patronize brothers like this all the time. I support black owned businesses and black people in their economic growth and development but I will not support bullshit. But the point is this. You can create your own job, ain’t no excuse for being a criminal. So fuck a root cause of violence, what’s the root of someone being an asshole? Poverty don’t make nobody kill. People kill for one reason only: HATE. People kill cause they’re just bad minded and hate filled. That’s it.

Here’s the truth about all of this. Faith Without Works is Dead. That’s the problem with the black church, mosque, synongogue, and Israelite Camp. They got a lot of Faith, but no action behind it. I’ve seen a lot of FAITH WITHOUT WORKS and FAITH WITHOUT WORKS IS DEAD. You got to take action where your at in order to see any change in your lives. The people in these inner city neighborhoods haven’t taken necessary action to change this, because if they had, things would have changed long ago. Had everyone of these parents and extended family members, sat down at night and helped these kids with homework and made education top priority above everything, regardless of anything going on, these young men and young women today would be performing at their best. That is a Fact. Another thing. You can blame White Supremacy and Racism for a number of things around socioeconomic inequality, because that’s a real issue, but here’s my thing. White Supremacy doesn’t control whether black children do their homework, take out the trash, wash dishes, clean their room, mown the lawn, or sweep up the front stoop. Nor does it control whether we as adults pick up a piece of trash and throw in the garbage and make our neighborhoods decent, clean, and dignified places to live. White Supremacy doesn’t control if your kids stay in school, excel academically, wait until they’re married to have kids, be in the house when the street lights are on, and behave themselves properly in society. No. These are all things in our lives that we control 100%. And I can 100% guarantee for a fact that when we take 100% ownership of these duties and act on them, we get positive results all around. The ultimate solution to the problem of crime, violence, and other social ills plaguing our neighborhoods is for each and everyone of us to take action on all of the things that are within our power to do, that we actually have control over. No matter insignificant or mundane it may seem do it. That’s how we change things.