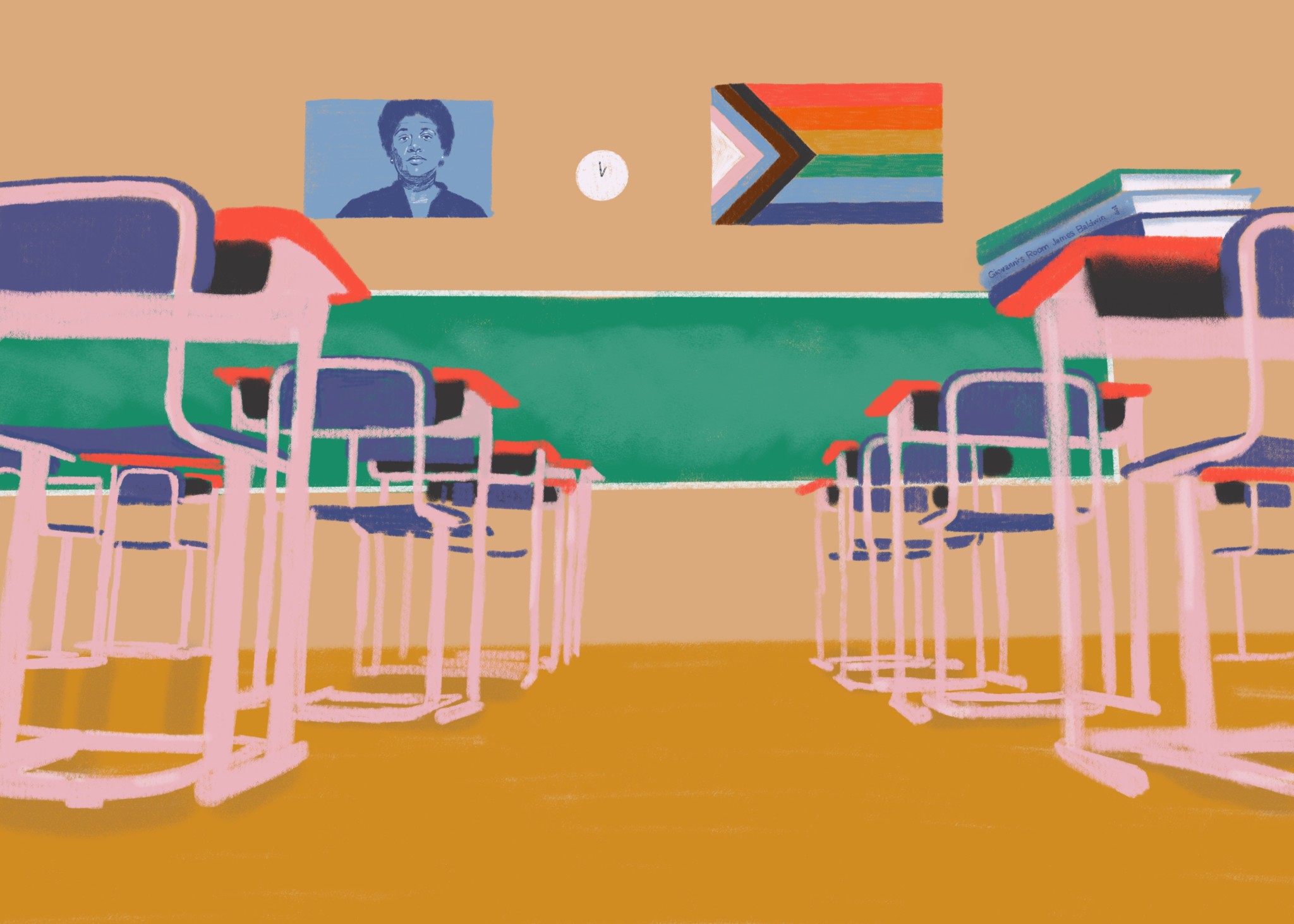

Last summer, Illinois passed the Inclusive Curriculum Law, making it the fifth state in the U.S. to require public schools to teach LGBTQ history. The bill, signed by Governor Pritzker on August 9, mandates that students learn the “roles and contributions of lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender people in the history of this country and this State” before they graduate eighth grade. The law will go into effect in the 2020–2021 school year.

Many activist organizations agree that a curriculum that incorporates LGBTQ people’s contributions to history is crucial to creating safer school environments for LGBTQ students. The Inclusive Curriculum Law was an initiative of the Illinois Safe Schools Alliance, Equality Illinois, and the Legacy Project. In a statement from Equality Illinois following its passage, Victor Salvo, Executive Director of the Legacy Project, called the bill “life-saving.”

An inclusive curriculum “creates a sense of belonging and acceptance that is baked into the DNA of a school,” Salvo told the Weekly. According to students, teachers, and advocacy organizations, student safety goes hand in hand with a diverse curriculum. In their 2017 National School Climate Survey, advocacy group GLSEN reported that LGBTQ students in schools with an LGBTQ-inclusive curriculum experienced lower levels of bullying, were less likely to miss school because they felt unsafe, and felt a greater sense of belonging in their school communities.

Although Illinois expanded its anti-bullying laws in 2014, requiring all school districts to develop policies to protect LGBTQ-identifying students from harassment, it is unclear whether students have actually seen any positive impacts from that policy. In January 2019, GLSEN reported that eighty percent of LGBTQ students in Illinois have heard homophobic remarks at school, while seventy-two percent have been harassed because of their sexual orientation or gender identity. Twenty-eight percent of students were disciplined by their schools for public displays of affection. The report attributed these numbers to a lack of school policies protecting LGBTQ students.

Sarah Baranoff, a drama teacher at Hancock High School, a selective enrollment public school on the Southwest Side, said she is unsurprised by these statistics. “I came out when I was fourteen. I’ve been stood on, I’ve had trash cans thrown at me. So having been through that, it doesn’t surprise me, because those kids are now parents.”

M, a recent graduate from a public school in the southwest suburbs who didn’t want to use her full name, came out during an oral history class in her senior year. When students in the class were asked how their senses of identity had changed over the course of the year, M decided to share her experience of balancing her queer and Muslim identities.“It takes a lot for you to come out of that shell and be really open about your queerness, especially being raised Muslim, or raised religious in general… There were sixty people in that class and none of them knew I was queer except for my group of five friends… That really caused a shift.”

M received numerous rape threats after she came out. Though she felt supported by the teacher of her oral history class, M didn’t consider talking to the school administration about the harassment she endured. “I’m a queer Muslim, I’m a woman… I don’t believe [the school administration] will change anything… Every time a minority speaks out against something that happens to them, it’s a he-said, she-said situation.”

Some school administrations may be more supportive of LGBTQ students than others. Baranoff said that the Hancock High School administration was quick to provide gender-neutral bathrooms, and recalled an incident in which administrators, teachers, and students rallied to the side of a student who was publicly shamed for being queer. Baranoff applauded her school’s administration for being “very forward-thinking in a way that other schools are not.”

Baranoff said that at her school, harassment against LGBTQ students often comes in the form of “micro-aggression style” comments, such as saying “that’s so gay” or misgendering trans students. She said many of her students face more mistreatment at home than they do at school. “I’ve had students whose parents have thrown them out, who have hauled them off to church to be prayed over, who have thrown out their possessions…I think a lot of the time, the parents are worse than the other students.”

Despite the threats she faced from her peers, M was able to find an affirming community at school. After growing up in a religious community that felt overwhelmingly straight, she surrounded herself with queer friends in high school. “We were all gay people of color, and it was just amazing… I was so grateful for them.”

Nathan Petithomme, the founder of Lindblom High School’s Gay-Straight Alliance (GSA), said that spaces for queer students of color are especially important on the South Side, where resources for LGBTQ youth can be sparse. He believes there is a perception that queer and trans youth don’t exist on the South Side. “People see being gay as a white thing. We don’t have people of color who are gay in the media as role models….People of color, especially Black people, have a harder time coming out as gay.”

The Lindblom GSA seeks to create a sense of community for queer students of color on the South Side. They hosted the South Side’s first GSA prom, and organized a mandatory workshop for teachers to discuss LGBTQ issues.

“Before GSA, there was definitely bullying, like using the f-slur, or using ‘gay’ in a derogatory way,” Petithomme said. “And I will say, after GSA’s formation a lot of that language died down. Teachers started to talk more about LGBT identities in their classrooms, and they started asking students what their preferred pronouns were.” Still, Petithomme suspects that there might be more GSAs in schools on the North Side than there are on the South Side.

Now a sophomore at Loyola University, Petithomme, who has contributed op-eds to the Weekly, is majoring in education because he believes that schools play a “big role in shaping social attitudes.” When it comes to the Inclusive Curriculum Law, Petithomme said that thorough implementation will be crucial. “The law can be made, but there are laws about Black history, and we only get taught a certain type of Black history…I want to make sure that the curriculum isn’t whitewashed, and that it includes the contributions of people of color to the [LGBTQ] movement.”

Indeed, in 1991, Illinois passed a state law to ensure that all public schools teach a unit on African American history. In 2013, twenty-two years after the law’s passage, community activists pressured CPS to fully comply with the law, citing complaints that Black history was only occasionally being taught during Black History Month. Later that year, CPS committed to implementing a curriculum which would go beyond the traditional subjects of slavery and the Civil Rights Movement. Despite this commitment, in 2016, teachers and activists still asserted that CPS had fallen short, claiming that Black history curriculums were being overlooked in favor of preparing students for standardized tests.

Implementing an LGBTQ history curriculum has also been a slow process in California, which was the first state to pass a law like the Inclusive Curriculum Law. Even though the law was passed in 2011, the state didn’t approve its first LGBTQ-inclusive textbooks until 2017, in part due to pushback from parents and conservative organizations. In 2018, the Bay Area Reporter predicted that it would take years for the textbooks to actually reach every classroom. “We have seen a lot of schools dragging their feet,” Dominic Le Fort, executive director of a California-based nonprofit called Queer Education, told the Reporter.

How widely the curriculum changes will be implemented across the state is left largely in the hands of local schools and individual teachers. The Inclusive Curriculum Law does not include specific mandates regarding which histories must be taught, or how many LGBTQ figures must be included in a school’s curricula. Technically, a school can comply with the law by including just one positive mention of an LGBTQ person in their lessons.

But Victor Salvo, executive director of the Legacy Project, is hopeful about the implementation of the Inclusive Curriculum Law. Salvo considers even minor changes to curriculum a “triumph,” particularly in downstate school districts where discussing queer issues might be particularly taboo. He said California’s FAIR Act was unique in that California was the first state to pass such a bill, and they faced well-funded, well-organized opposition at the time. Unlike the Inclusive Curriculum Law, the FAIR Act required the printing of new textbooks, which made it easy for conservative organizations to oppose the bill based solely on the financial strain it placed on the state. The Inclusive Curriculum Law was explicitly written to require no new funding, so districts are not required to buy new textbooks.

Together, the Legacy Project, the Illinois Safe School Alliance, and Equality Illinois are working to ensure that the Inclusive Curriculum Law is implemented smoothly. The Illinois Safe School Alliance is creating professional development programs for teachers, while the Legacy Project is collecting materials that teachers will be able to reference as they develop curricula for the 2020-2021 school year. Because all of the materials will be available online, Salvo predicts that costs to school districts will be negligible. The sampling of lesson plans on the Legacy Project’s website includes lessons about a diverse range of LGBTQ historical figures, including Alan Turing, James Baldwin, Frida Kahlo, Audre Lorde, and Jane Addams. According to Salvo, many of these figures are already part of the curricula, but there is often no mention of their LGBTQ identities.

Hancock High School teacher Sarah Baranoff agrees that student safety is inseparable from an inclusive curriculum. She said that her job is to ensure that her students get a good education, which can only happen if they are safe. Representation matters, she adds. “The more diversity of stories we have out there, the better for all students,” Baranoff said. “What we need to be teaching them is that every voice matters, and that their story is powerful, and that they are capable of having their voice heard and respected.”

Anna Attie is a student at the University of Chicago studying English Literature and Human Rights. She is a first time contributor to the Weekly.