On Saturday, October 28th, WHPK DJs took to the University of Chicago quad and spun all day to publicize their #SaveWHPK protest campaign. The Weekly streamed part of the event over Facebook Live.

On a Tuesday in late September, Tuyaa Montgomery, a twenty-year-old University of Chicago student, walked into the second-floor studio of WHPK, the college radio station based out of the campus’s Reynolds Club student center at 57th Street and University Avenue. She’d come to organize the heavy metal CD collection, frequently left in disarray on one of the highest shelves in the studio. She climbed a ladder, pulled down the CDs, spread them out on the floor, and started to sort. There, on one of the CDs, she saw something that horrified her: not the usual gruesome imagery of a metal CD, but what she was almost sure was a bed bug.

“My heart dropped,” she later said. “I was like, oh god. Here it comes again.”

That Tuesday was only the station’s second day of broadcasting this fall: WHPK had returned after a summer of intermittent dead air, a persistent bedbug problem, and constant political conflict. Many DJs have left, broadcasting hours have been shortened, and nothing will ever be quite the same. In future histories of WHPK, this summer will have its own tragic chapter.

At night during the week, on the rock format, most of the DJs are UofC students. But during the day and on weekend nights, most of the DJs are not students or faculty—they are, in the parlance of the station, “community DJs.” Programming on the station varies. There’s talk and soul, jazz and hip-hop. The level of expertise of the DJs also varies; new student DJs will cut their teeth in the early hours of the morning, while later that day a DJ who’s been around the station since 1980 will spin soul for loyal fans from the same few turntables and worn-down console.

The influence of the station is storied; DJ J.P. Chill’s show, which started in 1986, is commonly said to have brought hip-hop to Chicago. James Earl Bonez, who inherited Chill’s hip-hop throne and timeslot (Friday at 10:30pm to Saturday at 3am) in the early 2000s, says that Chicagoans above a certain age all first encountered hip-hop through that show. Kanye West and Common are among that generation; the two once traded verses in the station’s studio. Common even shouts out the station on his album Resurrection.

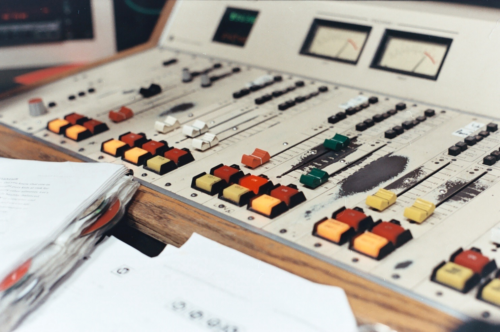

Things haven’t always been perfect at WHPK. Gary Tyson, a soul DJ who’s been around the station since 1980 (off and on in the early years, and then consistently since ’98), remembers a few incidents: “DJs have been passed out on air and the record’s still playing…there’s been graffiti, you know, on the station wall. There’s been records that have been stolen,” he said. The equipment presents its own problems: one of the CD players scratches CDs, and knobs are missing from the old analog soundboard. But despite technical difficulties and internal conflict, the station has persisted, always as a notably positive point of contact between the UofC and its surrounding community, both inside and outside the studio.

Then, in March of 2016, the real trouble began. First, the UofC announced that all non-student, non-faculty DJs would have to undergo background checks. This decision, they claimed, wasn’t sparked by any specific incident and is unrelated to any other changes at the station.

“As a matter of policy, UChicago regular staff employees undergo routine criminal background and registered sex offender checks at the time of hire,” reads the statement. “Such checks can help inform decisions about an applicant’s suitability for a position, though having a criminal conviction does not automatically preclude employment. In keeping with this practice, the University is requiring the same of volunteers whose work with RSOs [Registered Student Organizations] includes extensive interaction with students or work in University facilities.”

“F.U.,” is how longtime DJ Mario Smith recalls his reaction to the news. Smith has hosted a talk radio show since 2001, hosting Public Enemy MC Chuck D, Talib Kweli, and the late Dr. Margaret Burroughs, among others. When not on air, he’s box office manager and occasional emcee at The Promontory: “To keep my voice sharp so I don’t sound crazy,” he says.

“You have known someone for fifteen years. You let them live in your house for fifteen years and then one day inexplicably out of the blue you say I need to know a little bit more about you. But you’ve known me for fifteen years!”

“When they first said they wanted to do a background check and everything, it bothered a lot of people,” says Bonez, the hip-hop DJ, who also works with the State Department of Children and Family Services. “But it didn’t bother me. I do background checks all the time. I understand you want to know who’s coming in and out, you want to know who’s in your building. That’s not an outrageous expectation.”

The last day before the consent form for the background check was due, Smith reluctantly turned it in. “It was, ‘Sign a background check and continue to have my voice out there or don’t sign the background check and see what they do.’ Well, I signed it.”

Then, on August 4, Smith received notice that bedbugs had been found in the studio, that the station would go off the air, and that he would have to get his house inspected before he could return. This wasn’t the first time bedbugs had been a problem for the station. As far back as 2014, stray bugs had been occasionally spotted. One metal DJ, Anneken, claims that he brought bedbugs home from the studio to his apartment three times. In late June, another metal DJ, Andrew Billingsley, spotted two bugs crawling out of the console during his show. In early August, another bug was spotted, and the studio was shut down for inspection.

No infestation was found, and it was therefore concluded that a DJ must have brought in the bugs. The university announced that each DJ would have to have their home inspected before they could return to the studio.

When Smith heard the news, he regretted bending the knee to the university’s first request for background checks. “I wish I wouldn’t have now,” he said, “because who knew that they would come up with these invisible bedbugs with lasers on their heads to try to scare the hell out of us.” He announced his resignation.

Tyson did the same; he sent his resignation the day after he received the email about bedbug inspections. “I just felt that that was the straw that broke the camel’s back for me.”

Even Bonez was frustrated with the situation.

“I’m like, that’s kind of strange, to want to come to my home to see if I have bedbugs,” he said. “But then on top of that, you want me to pay for the inspection when you don’t pay me in the first place!”

But Bonez stuck with the station. “I complied with the background checks, I complied with the inspection of my home for bedbugs. You know, even though people were like you’re crazy, I would never. Naw. I want the show. I want to be part of WHPK.”

Initially, the inspection cost fifty dollars through the university-approved company Smithereen Pest Management. In an attempt to stem the outward flow of longtime DJs, WHPK station manager Zach Yost negotiated with the university to use funds from WHPK’s spring concert to pay for DJ home inspections.

“I’m sure it’s been hellish for [Yost] to be caught up in this,” said Bonez. Yost, a third-year undergraduate at the UofC, became station manager in May. So far, it hasn’t been easy; he’s the wartime president of WHPK, faced with endless diplomacy. He’s the main liaison with the administrative representatives from the Center for Leadership and Involvement (CLI), the UofC department that oversees student organizations like WHPK. He’s tasked with ensuring the station complies with the FCC’s broadcasting requirements so that the 88.5 bandwidth doesn’t go up for sale. And, most of all, he’s tasked with communicating with all the DJs: he’s had the unenviable duty of writing every unpopular announcement email. After Yost was quoted in a DNAinfo article, he was told by the university that because of his stipend for the position, he was officially an employee and would have to consult with the UofC communications office before talking to members of the press.

Andrew Fialkowski is the most senior administrator at WHPK who doesn’t get a stipend. Now a fourth-year undergraduate and the station’s music director, he started DJing in his first year and has filled various roles ever since. By his estimate, this makes him one of the two longest-standing student DJs. But his three years are peanuts compared to a DJ like Tyson, and, as he observes, this is a peculiar feature of the station: as a student organization, the leadership is always comprised of UofC students who come and go, their short reigns leaving the station unstable, while many community DJs have worked at the station for decades.

Fialkowski was gone this summer, in California interning for a public radio station, but he’d heard tell of all the recent trials. On August 24 , he said, Yost sat down with Sarah Cunningham, the head of the Center for Leadership and Involvement. Yost was presented with a list of changes for the station. These changes included some much needed upgrades: a new coat of paint, new furniture and carpeting, and a brand new key card lock system, which would allow DJs to access the studio and music library more easily.

But one new policy in particular stuck out from the rest: when the doors of Reynolds Club are closed, at night and during breaks, WHPK wouldn’t have access to its studio, where DJs have been broadcasting twenty-four hours a day since 1982.

Of the decision, the university stated: “CLI did not reduce WHPK’s hours and they are not being forced to cut programming. On the contrary, the DJs have been informed that WHPK is aggressively working on solutions that include remote broadcasting capabilities and a possible satellite location. CLI is working in partnership with WHPK to work out the remote broadcasting logistics.”

The university proposed some workarounds; DJs could broadcast off their laptops from home, or maybe the station could find a place to set up a satellite location where DJs could broadcast when the studio was inaccessible.

Fialkowski describes that proposal as the most “kind of sci-fi, goofy part of the story.” Some DJs, he says, don’t have laptops, high-speed internet, the technological know-how, or the time to put up with the switch. Bonez was similarly skeptical: “I’m like, this is the radio station that half the time couldn’t keep the phones working,” he said.

A radio station that “half the time couldn’t keep the phones working” could stand to get some upgrades.

“You go to those places [like Northwestern] and you see their radio stations, it’s all digital, all high-tech. You go to WHPK, it’s like the first soundboard,” said Bonez. But what makes WHPK special, Bonez says, has historically been the lack of oversight that went along with a level of neglect. “As long as you don’t tell me what to play, I’ll use your board,” he described it.

In the past, Bonez was always frustrated when the UofC did get around to putting a fresh coat of paint on the studio walls. “I’d be so pissed off,” he says, “because I would just be like, yeah I know you just look at it when you come in, but do you know how many people have signed this wall? Like, great artists?”

“I don’t know if the university understands what it provides,” he says. “Maybe it does, maybe it doesn’t care, I’m not sure, I’m not at the administrative level to hear those meetings, we just get emails of what’s been decided from Mount Olympus.”

On September 24, four days after Montgomery found the lone bedbug that put the station temporarily off air once again, WHPK returned to the airwaves on a limited schedule. As it stands, the station broadcasts from seven in the morning to midnight on weekdays, eight to midnight Saturday, and nine to midnight Sunday. Student DJs on the rock format, which used to run throughout the night, have mostly been given shorter shifts in the morning.

“WHPK is dead,” says Smith. “However the station is gong to sound when it comes back on, it isn’t going to sound like what it was when I was there.” The same goes for Tyson. Bonez, though, is still around, although his show, which used to go until 3am, now ends at midnight.

Great read! A unfortunate example of the callousness of bureaucracy.

So sad that U of C doesn’t get the historic significance of what talent the have with long-time DJs. It’s like permitting Jimmie Hendrix to practice in your dilapidated garage for 30 years before calling city inspectors due to code violations. REALLY??!!

I think after 30 years you’d probably want Jimmie out of your garage. Especially if it started becoming infested. I think your analogy is an accurate one in that sense: there are people who would love to have an aging Jimmie Hendrix hanging around for 30+ years (or in this case some of his followers)… but not many, and certainly not if your garage is in a University.

WHPK was great, and it’s best to remember it that way.

You mention JP Chill who had a hip hop show starting back in the mid 80s but the link given is not him. JP is actually a Caucasian gentleman. Please do more research and correct the link if you can find him.