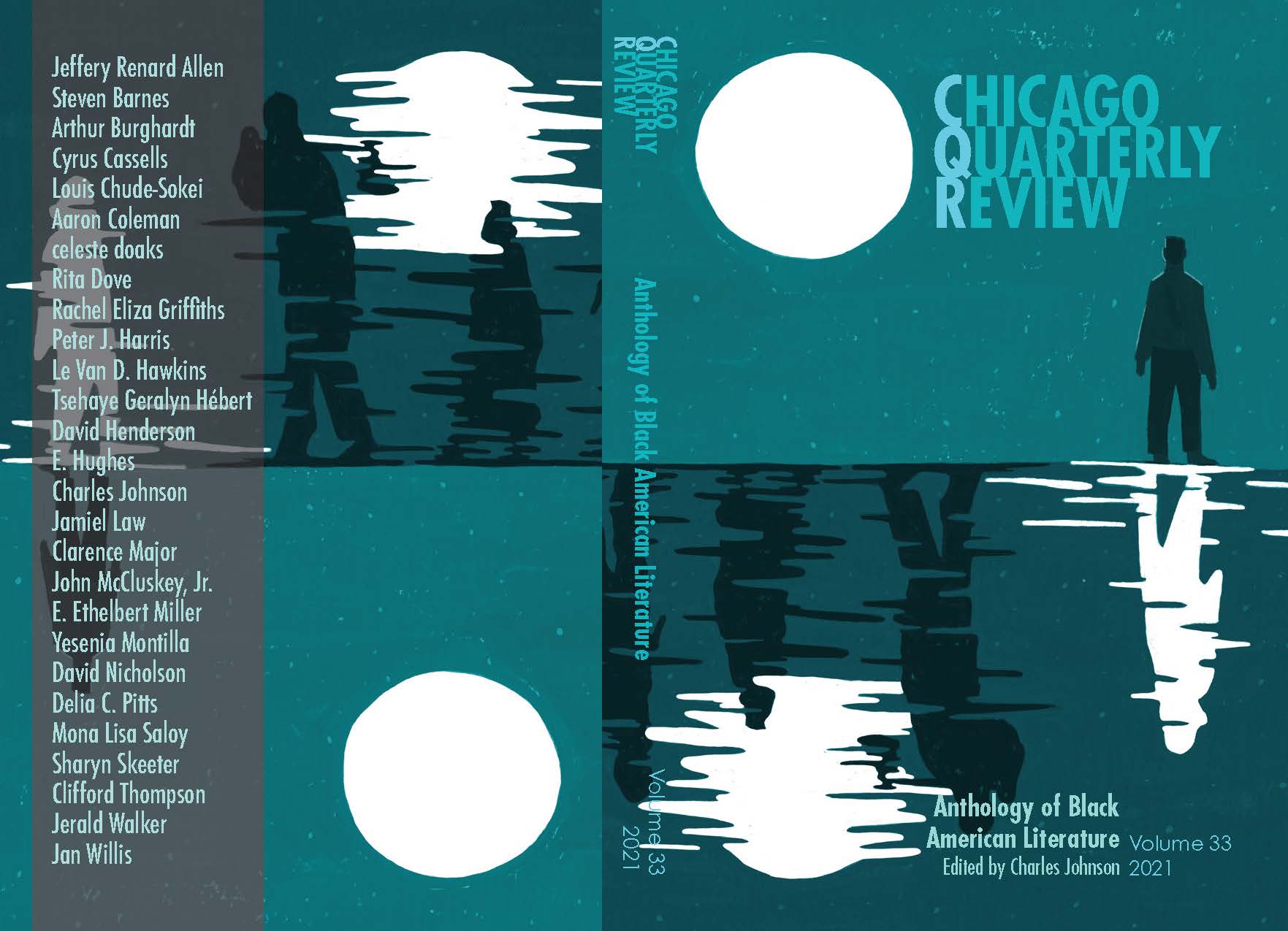

Being Black is not a monolithic existence. You can’t know one of us and know all of us. You can’t truly know the Black experience—or any other than your own—without living it, being immersed in it from innards to outwards. Yet in reading the Chicago Quarterly Review’s new Anthology of Black American Literature, where gifted writers, poets, and artists shed their truths, anyone of open heart and mind can empathize with the joys, struggles, accomplishments, and recursiveness of being Black in America.

Though the table of contents is divided by genre—fiction, nonfiction, poetry, and art—the work within is interspersed so that you don’t know what you’re getting until you get there. Though the purpose of the anthology is to “capture the great diversity of thought, feeling and life of Black America,” according to CQR managing editor Gary Houston, I read from one story, poem, or essay to the next, glad that I could not predict the essence of the piece but also thankful for the cultural and human connections.

In his introduction to the collection, National Book Award-winning novelist, philosopher, and guest editor Charles Johnson discusses the work in the anthology as it relates to six cultural themes: the collective Black past; historical reimagining of that past; group trauma; the existential pain some struggle within their Blackness; cultural appropriation; and intersection of worlds, cultures, people, and circumstances. Johnson was right to do so, considering the recent isolation, death tolls, and life compromises of the pandemic, the gun violence happening in neighborhoods populated by people of color, the poor, and the hopeless, and the political upheavals that have divided family, friends, and neighbors.

I found the work in the Anthology of Black American Literature to be like studying an impressionist art form, where understanding and perspective can be individual as well as collective. From my own prism, I developed my own categories based on the wide realm of emotions and vulnerability.

When I began to read “Doctor King’s Queens,” an excerpt from the recently completed novel My Gingerbread Shakespeare, by Cyrus Cassells, I was quickly drawn into the conversational and sometimes conspiratorial narrative of Duncan Thaddeus Metcalfe, the great love of fictional Harlem Renaissance poet Maceo Hartnell Mitchell and a celebrity in his own right, known to the press and his fans as the “Black Gable.” A baritone singer and an actor, Duncan has been asked to sing, per the request of Maceo’s sister, at the funeral of slain civil rights activist Dr. Frederick Douglas Kinnison. Before affirming his participation, Duncan decides to do a little reconnaissance. In Doc Kinnison, Duncan discovers a kindred spirit, a gay man with a colorful past and like himself, one of the many gay men recruited by Bayard Rustin to join Dr. Martin Luther King in the fight for civil rights.

“We were all of us battle-ready privates in Bayard’s fast-growing army; in his giant Hell no! to unjust Jim Crow,” writes Cassells. Reading Duncan’s tales was like “dishing tea” with a friend while also stirring in the unspoken contributions of gay Black men to the civil rights movement. Duncan’s “tongue and cheek” narrative vacillates between lighthearted and serious tones, particularly when his young lover and freedom fighter is murdered while teaching Mississippi Delta kids how to read.

The short story “that’s why darkies were born,” by David Nicholson, also won my attention. In it, Nicholson tackles that African proverb that says, “Until the lions have their own historians, the history of the hunt will always glorify the hunter.” Nicholson allows the lions of classics like Huckleberry Finn and Gone with the Wind to speak their truths. James reframes the story of Huck Finn by admonishing Huck or misrepresenting the actual way James (Jim) spoke or the real reason they’ve joined forces. In Nicholson’s reimagining, James was a free, educated man from a family of means until he left home to travel, but before he could reach his destination, his manumission papers were absconded by the law and ruled fraudulent by a judge who allows James to be sold into an institution of slavery his family had not experienced for two generations.

“I was seized, chained, and thrown rudely into the frame hut that served as a jail,” writes Nicholson, in Jim’s voice. “In the morning, Judge Thatcher ruled my letter no proof I was free, the law recognizing only manumission papers filed with the court and certified by the legislature. I protested, cajoled, threatened even, in the end, offered bribes. It was no use. I was declared property and sold in short order. Once James, a free man, I was now N***** Jim, diminished in name and status.”

Afterwards, Jim concocts a way to reclaim his freedom by throwing in with a shiftless young man who has a raft and pole and knows his way around a river. In “that’s why darkies are born,” among other prose and poems in the collection, the writers allow formerly subdued voices to rise to the surface and tell their own stories.

Two poems, “Of Walking In,” by Aaron Coleman, and “Brother Eric Garner,” by David Henderson, speak to the concept of shared trauma, acting as gateways to hard but necessary conversations and posing various ways to look at common social ailments, from the challenge of simply walking while male and Black to the murders of unarmed Black men by the police.

With “Of Walking In,” Coleman tackles the common dilemma faced by Black men who need to present the façade of living with dignity and freedom in America, even if it is an act:

Shout-singing their favorite pop hip hop songs

In order to perform a riddle and posture

Of freedom.

Later he writes:

But I know I felt the black weightlessness

In the practice of letting go

Of public fear and private shame

In public space. Untaken, but noticed.

Henderson’s “Brother Eric Garner” shatters the fallacy that portrays Garner a criminal. To be clear, yes, Eric Garner sold single cigarettes to people “who lacked the funds to invest in a 13-dollar pack of smokes.” But, on the day of his death, he wasn’t doing anything unlawful. In fact, according to Henderson, he was on his way to pick up groceries for his family and stopped to help the police break up a fight before they turned on him. At the end of the poem, Henderson wonders if Garner would have lived had he fought the men in blue who unwarrantedly attacked him. This left me thinking fight or flight, with the wrong officer, while retaining your life is a toss-up.

A common conservative complaint about Black Lives Matter and other social justice activism is that Black people are always complaining about the police when they are killing each other, even though the U.S. Department of Justice found the rates of white-on-white and Black-on-Black homicides similar, at around eighty and ninety percent. Even so, the fear, anger, sadness, and frustration of dealing with neighborhood violence hits you in the gut when you read “Off the Wall” by Tsehaye Geralyn Hérbert.

In this short work, Josie, a mother and teacher who wears sensible shoes, takes on the apathy of a community content to build memorials for kids who have been shot down or killed in their prime. Tired of memorials that do nothing but expand, Josie purchases several cans of spray paint from an auto shop and at her own peril, sprays over a memorial of slash marks (one for each murder) amidst a growing crowd of dissenters and supporters. Josie questions the purpose of creating one memorial after another when another child is posed to die. “I am sick and tired of the killing,” writes Herbert. “These are our kids.”

Each piece in the Anthology of Black American Literature takes you on a journey that can be terrifying, disturbing, beautiful, tender, moving, or enlightening. The writing is impressionistic in that two people may read the same prose and have different insights or perspectives, but each reader will walk away lifted in knowledge or empathy. The anthology is a long-time investment. My own copy is already dog-eared and populated with protruding post-it notes and marginal annotations. I will return to these essays, stories, and poems often for my own edification and that of my students because the Black experience as chronicled in the Anthology shows our humanity in all its beautiful imperfections, struggles, and triumphs.

Charles Johnson, guest editor, Chicago Quarterly Review, Vol. 33: An Anthology of Black American Literature, Chicago Quarterly Review, $24/2 issues, 254 pages.

Tina Jenkins Bell is a freelance journalist. She has written for Shareable.net, Alaska Magazine, Chicago Tribune, San Francisco Free Press, Crain’s Chicago Business, CNet, the Villager, and a host of other publications. She routinely blogs for Chicago Writers Association, For Love of Writing (FLOW), and AuthorPublish. This is her first piece for the Weekly.