The tree set in the middle of the eta stage is a riot of color. Its trunk, painted with streaks of neon, is strewn with vines and stamped with a variety of West African adinkra icons. Hanging from a branch is a lone, glittering red ornament—the apple in this retelling of the biblical origin story, and a nod to Christmas and the tradition of nativity plays, to which In De’ Beginnin’ pays slight homage with the timing of its current run. The prominent and idiosyncratic set piece, however, is the first clue that this retelling of the origin story will be anything but by The Book.

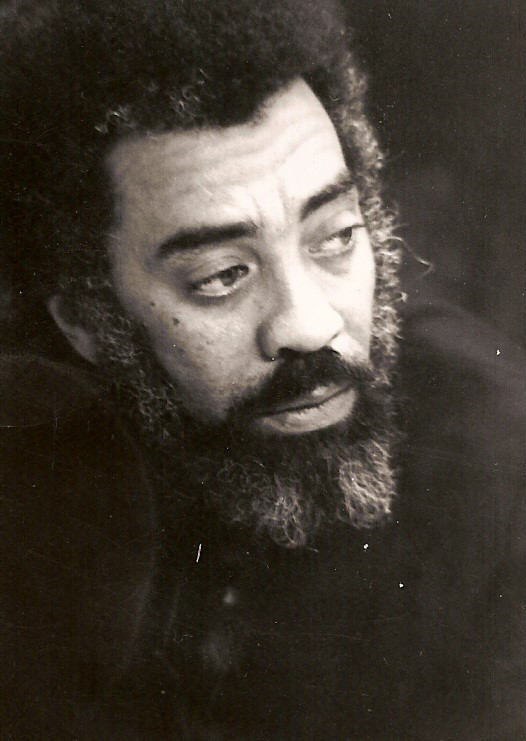

Written by the late Oscar Brown Jr., In De’ Beginnin’ is, simply put, a Genesis story. It tells the tale of biblical creation and the events that led to the banishment of Adam and Eve from the Garden of Eden. But it’s also much more than a simple Biblical reenactment. Director Kemati Porter and Musical Director Maggie Brown told the Weekly about its deeply particular modes of storytelling—the entire musical is told through a particular dialect with dropped consonants and slang, dialogue is spoken in rhyming verse, and the songs, written by Oscar Brown Jr., his son, Oscar Brown III, and Calvin “Coco” Brunson, carry the same smooth jazz tones that they honed in clubs on the South Side.

All of these elements came together as soon as Brunson took his place behind a modest keyboard stand on stage left. As the first notes rang out, the seven-member cast jubilantly sashayed onstage, a choral outburst marked by brightly colored costumes and strikingly contrasting nude bodysuits which made it immediately clear who played the roles of Adam and Eve. Pastor Tamara Bennett, clad in a rainbow bell-sleeved dress, and Colin Jones, playing the part of the Rev, worked the audience in these first moments of the play, pulling together a heady show of energetic narration and eliciting call-and-response participation. “Amen!” the audience would yell back as Bennett sang. This communal-yet-intimate atmosphere was sustained through most of the first half of the play, mainly by Jones, who would interject scenes with his narrative passages and an insistent preacher’s aura summoned through sheer force of voice and glistening sweat on his forehead. It felt a lot like going to church: fellow audience members would often break out into laughter or smile widely and wildly at the scenes onstage. Within the eta theater, as In De’ Beginnin’ played, it seemed like a strange sense of community was being constructed.

This sense of intimacy, of family even, is unsurprising, considering the roots of the play. Brown, the musical director of the show and the daughter of Oscar Brown Jr., recalls when In De’ Beginnin’ was first staged at The Body Politic Theater in Lincoln Park during the late 1970s. “It was a family affair originally, where my older sister played the Lawd, my younger sister played Eve, and my dad was the Rev, and my brother was in the band, and my cousin was the Devil, and my stepmother was the Serpent. So it was straight family. It really was,” Brown said.

The family affair continued even after the play was re-staged by The Chicago Theater Company, with Africa Brown, the younger sister of Maggie, then reprising the role of Eve. Through all its previous runs, In De’ Beginnin’ has always been at some level about family, communities, and the intimacies that these circles contain. It was no surprise, then, and the perfect convergence, that this latest re-staging of the show would be taken up by eta, itself an organization more like a family than any bureaucratic institution.

Porter and Brown both said the initial process of getting In De’ Beginnin’ to the eta stage was a collaborative process more than anything else. Early in the year, Brown had put out a call to various theaters, dance companies, and creative organizations, looking for those interested in staging works of Oscar Brown Jr. Already heavily involved in a process to commemorate and celebrate her father’s legacy for what would have been his ninetieth birthday, Brown hoped that 2016 would be “the year of Oscar Brown Jr.,” with music festivals, readings, panel discussions, and more in mind. Porter, on behalf of eta, responded to that initial call, finally selecting In De’ Beginnin’ as a family-friendly musical production for their holiday season. It was an apt coming together of the work of a Chicago legend, also hailed for his grassroots-level advocacy and engagement, and a theater that has been similarly committed.

In this same vein, the process of calling, auditioning, and working with actors for the show was focused on nurturing and training rather than any cutthroat competitiveness. Porter reiterated, “Our mission is a training mission—to train artists. [The play] was a great opportunity for some artists to understand and explore that philosophy because we don’t know about it. So we were all jumping into the water together not knowing what the hell we were getting into but it was going to be a good something. That I was sure about.”

The process of training and rehearsals was still fraught with challenges, however, partly because of the requirement of actors to both sing and act, as well as the dialogue—a killer combination of rhyming verse and what Brown describes as a “Negro dialect.” “It takes time to learn that. To unlearn what you know and learn something new, to drop consonants,” Porter said, to which Brown adds, “Cause you been trained to be proper. Now we’re saying ‘No. Let it go.’”

The dialect is immediately striking, but Brown also points out that the verse is written in iambic pentameter, and, even more noticeably, rhyming quatrains. “I mean, who did that apart from Shakespeare?” she laughed. The spoken word in In De’ Beginnin’, with its cadences and specific intonations, is already difficult—add to it the humor that it’s supposed to evoke, and it seems a near miracle that the actors are performing the dialogue in any smooth way. Brown chuckled, “[My father] was a funny cat, and sometimes the youth of actors, they don’t even realize what they’re saying. They don’t even realize the wittiness of what or how they can say that. But they grow into it. And I look forward to every passing show, and I think they’re going to sink teeth a little further and embody these words.”

It’s a hope well-placed, with some truly standout performances, especially in the second half of the show. Fania Bourn’s Eve, who saunters on after being conjured from Adam’s rib by the Lawd, has a stage presence that immediately captures the attention of an audience, and clearly of Adam. The fool-like Adam, played by Khyel Sherman Roberson, is entranced, and trails after Eve, speechless and hapless. Even while she croons “I’m with you,” slowly leading him offstage, it is clear that she is in charge, a dynamic that plays out later in a hilarious feat of physical fight comedy between the two. As Eve defeats Adam, Bourn’s reprisal of this battle of the sexes tune sees her belting center stage, fists raised and punching, a call to arms for herself and a moment that showcases her stunning voice. Despite her simultaneous punching, Bourn easily hits the higher registers in the song, her voice resounding around the theater, a welcome echo.

Musically, In De’ Beginnin’ is a tour de force, especially with Calvin Brunson behind the keyboard. Brown emphasized that live music was crucial for the show, saying that recorded tracks were an option initially, “but this show would suffer greatly. It’s not meant for a recorded track. It’s meant for someone who can play along, and the music kind of introduces scenes and gives punctuation to different moods of the show.”

This natural rhythm is wonderfully conducted through Brunson’s playing. During the show, he appears to the audience as nothing but a shadowed figure behind a keyboard on stage left. But as the songs begin, the figure sways, jerks, and moves to the tunes, Brunson himself responding to the musical moods he creates. As one of the original creators of the music, his involvement was a no-brainer for Brown and Porter. The former recounts how a teenage Brunson used to play music with her brother and her father until they were old enough to get into clubs and play there. “He’d been playing with my father and collaborating on a lot of songs and actual whole plays like this one and Journey Through Forever,” she pointed out, citing a long family history and familiarity with the work.

As the play navigates its way through the second half, more sinister themes surface, and Kai A. Ealy’s turn as the Devil/Serpent takes on an outstandingly decadent villainous quality. His solo, in which the refrain “Your destruction, your damnation, and your death” reverberates in the once church-like atmosphere of the theater, is unnervingly entertaining. It’s an impressive performance that sees Ealy embody the slithering physicality of the Serpent character—eyes bulging, gait smooth and purposeful, and voice digitally mangled to take on a slightly ear-piercing register. As the play progresses and we see the inevitable temptation of Eve, the implication of Adam, and their banishment from the Garden, the words and music of Oscar Brown Jr. continue to guide the narrative journey, before ending in a final song with the parting words, “Now you know you’ll die.” It’s a chilling last statement, a final memento mori wrapped in a joyful tune, and a reminder of mortality that leaves audiences just slightly shaken in their entertained state.

Yet the ending also encapsulates so much of what Oscar Brown Jr.’s work does—provide humor, words, song, and healing to situations and states often too difficult or painful to discern. Brown talked about the powerful social and civic work that her father did in the 1950’s and 1960’s, explaining that he started touring and performing in schools like Dunbar Vocational High School and DuSable High School and then put his attention to working with gangs like the Blackstone Rangers. “He endeared himself.” Brown said. “Certain people got a glimpse at how you could really use your art to come to your own rescue. Economically, spiritually, morally.”

In De’ Beginnin’ highlights this legacy of humor in direness, of lyricism in somber times, and most of all, of art as a method of healing for the community. Porter stressed this last feature in discussing Oscar Brown Jr.’s work: “He was very much an artist of the community. We can take care of ourselves, and art is one way of doing that. And I think that’s just the consummate … artist. That’s the consummate artist, who understands that the gift that they have is the gift that can heal.”