In 2023, the year renowned literary author Sandra Jackson-Opoku turned seventy, she gave herself a piece of advice: put up or shut up.

Realizing she had more days behind her than ahead only fueled her. “I’m still productive and working, though I have less time to do it,” she said. “So there’s a constant pressure from outside, and then this internal pressure to get things done, get things out, and make my mark while I’m still here.”

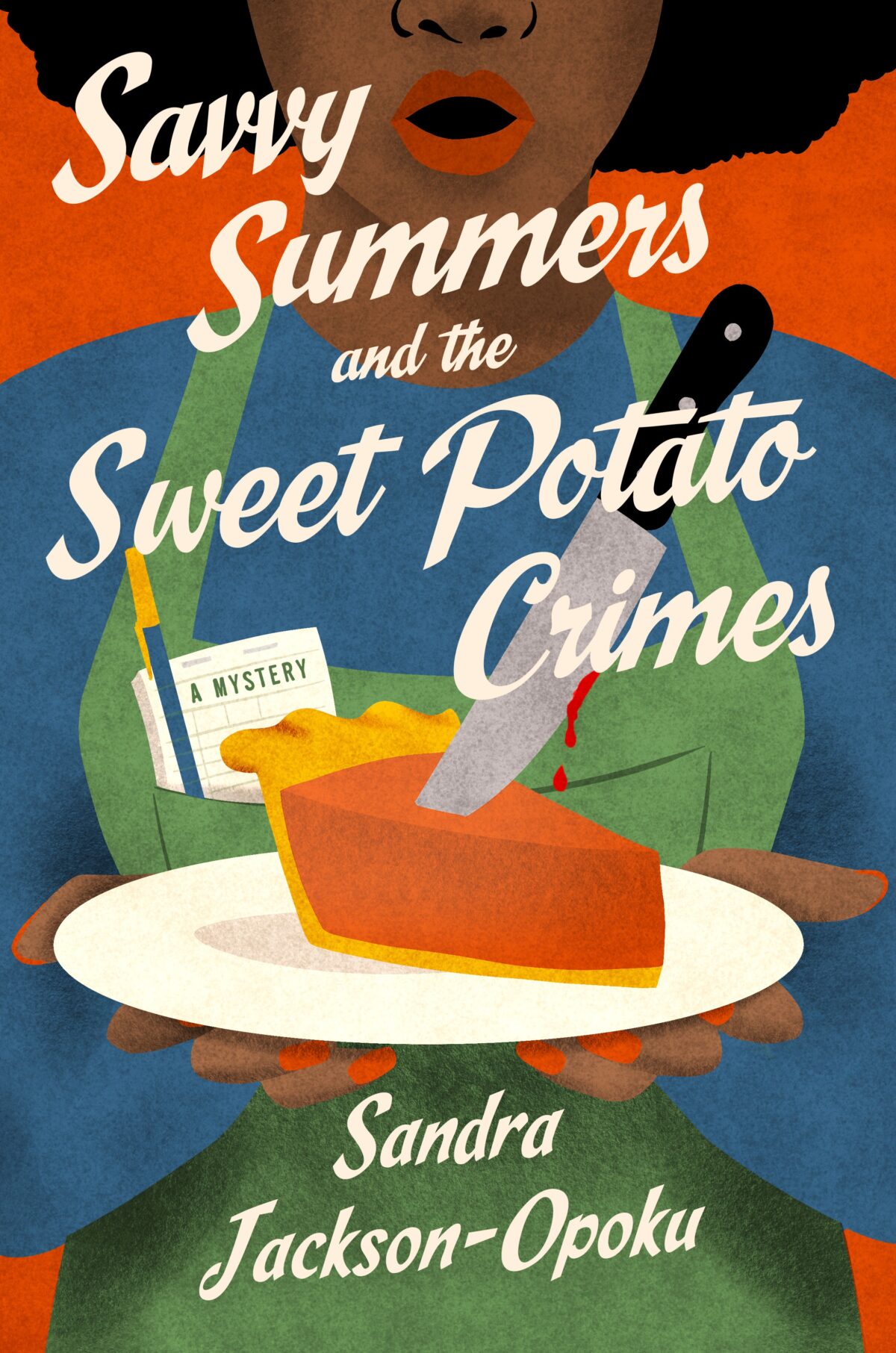

In July, a little over two decades after Jackson-Opoku’s last novel was published, Minotaur Books released her first cozy mystery, Savvy Summers and the Sweet Potato Crimes, to wide acclaim. Jackson-Opoku is as giddy with her new book’s success as she is proud of the hard work she put into changing her status from a formerly to currently published novelist. Moving from one stage to another wasn’t easy. She had to wade through ageism, genre biases, and industry expectations to get where she is today.

To be clear, Jackson-Opoku has never been one to twiddle her thumbs and wait for opportunity to find her. In 1997, her first book, The River Where Blood Is Born, was released by Random House. The novel won an American Library Association Black Caucus Literary Award. It also garnered the attention of Jada Pinkett Smith, who listed the book on her Black History Instagram lineup. A second book, Hot Johnny (and the Women Who Loved Him), came out in 2001 and was an Essence Magazine Bestseller in Hardcover Fiction.

During those years, Jackson-Opoku raised two children, freelanced, and devoted her time to longer fiction projects. But as her children came of age, she felt the need to stabilize her income and began to teach full time and write part time.

“It’s hard for me to write while I’m teaching because a lot of that energy goes into teaching…the interaction with students and worrying about them,” Jackson-Opoku said. “I continued to write,” publishing travel writing, essays, and short stories, “but it was hard for me to write in the long form,” so longer projects went unfinished.

In 2016, she retired from her university teaching job and returned her attention to projects she had “back-burnered.”

Jackson-Opoku co-edited Revise the Psalm: Work Celebrating the Writing of Gwendolyn Brooks, which was released in 2017 by Curbside Splendor. In 2022, Lifeline Theatre produced her play Hungry Ghost Festival. Jackson-Opoku also completed numerous shorter works and four novel-length drafts, participated in screenwriting mentorships, and won fellowships and coveted residencies. She had not, however, published a novel in over twenty years. That would change in 2025, with a bit of a plot twist.

She won the Minotaur Books/Malice Domestic Best First Traditional Mystery Novel competition in 2023. This achievement led to the publication and release two years later of Savvy Summers and the Sweet Potato Crimes.

The book is set in Woodlawn, where Savvy’s diners belt out lyrical Black witticisms and love on Savvy’s soul food and sweet potato pie. When an elderly man dies after eating a slice of Savvy’s pie, the pendulum of success swings for her restaurant, turning the beloved community eatery and gathering place into almost a ghost town. On top of that, an unscrupulous developer targets Savvy’s property and restaurant for acquisition and gentrification. Faced with these seemingly insurmountable challenges, Savvy could give up, take the paltry funds offered by the developer, and move on. Instead, she becomes an amateur sleuth, rooting out the real killer and shedding light on the developer’s evil doings. Savvy wins in the end, retaining her position as trusted community stalwart and beloved soul food restaurateur.

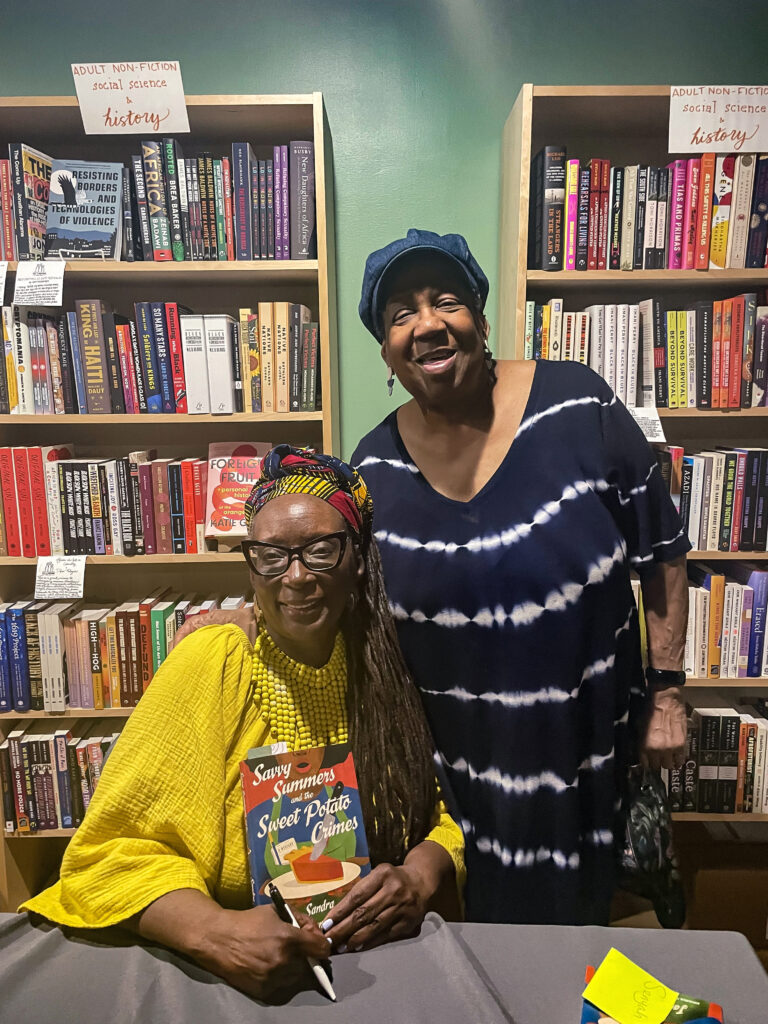

In just a few months since its launch, Savvy Summers has been eagerly embraced. On August 6, more than forty people showed up to celebrate Jackson-Opoku and her new book at Call and Response Books in Kenwood. In addition to the bookstore, the book launch was co-hosted by Jackson-Opoku’s longtime writing group, For Love of Writing, including members Lydia Barnes, April Gary, Janice Tuck Lively, Heather Roberts, and Tina Jenkins Bell, author of this article. Since then, she said requests for appearances to discuss the book have filled her calendar. She’s elated about her book’s reception among readers and in the publishing industry, describing the positive reviews and book club selections as “an embarrassment of riches.”

While basking in the early successes of her first cozy, Jackson-Opoku is working on a second installation of the Savvy Summers series, Savvy Summers and the Po’boy Perils. Achievements are often hard won, but despite the variety of challenges and the uncomfortable perception of lapsing time, Jackson-Opoku said, she had “to make things work.”

Jackson-Opoku is an author whose literary and historical stories cross borders, oceans, and shores to unravel and reveal the stories of Black people living in the African diaspora. Her focus remained on her work, never aging, until she heard an agent bragging about the youth of a new client.

“That gave me pause because it made me realize this could be a factor in the industry—whether it’s agents…publishers…editors…looking at you and counting up the productive years that they think you have left and possibly making professional decisions based on that,” she said. “So while I have never been a person who was ashamed of my age…I’ve started to be a little reticent.”

Chicago author Maud Lavin, who is close in age to Jackson-Opoku, shares her concern about the industry’s obsession with authors’ book-producing years and public appeal. “You can’t help but internalize some of this stuff. Like I want to do something new, but I’m not exactly thirty-two or living in New York…Screw that. It’s just another trap,” Lavin said. “I love how [Jackson-Opoku]’s dealing with aging. It’s like, ‘What the hell; I’m going to do what I want to do.’”

For decades, the publishing industry has considered literary fiction, with its depth of theme, character, and moral complexities, as “highbrow” and treated genre fiction as “lowbrow” for its formulaic structure, predictability, relatability, and high reader appeal.

Jackson-Opoku, whose first two books were literary novels, grew up reading mysteries and has always loved the genre. Still, she worried about writing them.

“I’ll be honest in that I was a little apprehensive about what people would think about the fact I’ve written and published a work of ‘genre’ fiction, because whatever reputation I have is as a literary writer,” she said. “I also feel like a story is a story. Whatever package you put it in, you can get across a message in many different forms. I feel like I’m following in a tradition of literary novelists who move back and forth very easily and gracefully between genres—people like Rita Mae Brown [and] Rudolfo Anaya.”

Jackson-Opoku also mentioned Valerie Wilson Wesley, whom she met years ago, and Native American author Sherman Alexie as accomplished writers who crossed from literary to genre fiction, including mysteries. Wesley and Alexie carved a path for other writers, wanting to let the story dictate the genre: “It’s kind of creative permission to experiment,” Jackson-Opoku said.

Tracy Clark, a Chicago-based author of eight mystery novels, finds the genre division inauthentic. “I try not to put a label on it…I’m okay with genre fiction. People denigrate the term, thinking it’s a lower quality of writing. It’s not,” she said. “The division between literary and genre is a marketing thing. It’s just them trying to figure out where to put you on the bookshelf. Writers shouldn’t have to worry about that; they should concern themselves with character and story. That’s it…That’s our job.”

“Sandra is hard to pigeonhole. She can write anything. If she wants to write literary, she can write literary. If she wants to write a poem, she can write a poem. If she wants to write cozy mysteries, like she’s doing with this series, that’s fine, too. But you have to sort of allow yourself this freedom to write whatever speaks to you,” Clark added.

Jackson-Opoku considered writing Savvy’s story in different ways before settling on a cozy mystery. At first, she thought it might be a nonfiction depiction of her female relatives’ Great Migration journeys or a memoir.

“But that started to be very research heavy, and I didn’t know if I was prepared to do that kind of excavation into family history,” Jackson-Opoku said. “There’s a lot of the people born in Mississippi that I don’t know, and relatives didn’t always want to talk about it. Some of those memories were painful or pragmatic—we’ve got to deal with what’s in front of us.”

Though she was unsure about the form, she moved forward, recognizing she had a character, a situation, “the whole idea of food,” and a setting.

Cozy mysteries are easily digestible and typically feature amateur (usually white) sleuths solving off-page murders in quaint settings in English or New England towns. But Jackson-Opoku grew up on Chicago’s West Side and has lived most of her adult life as a South Sider, in Hyde Park and Woodlawn. Wanting to write a “cozy” with familiar characters and settings, she treated hers in the true tradition of Black women in the kitchen, cooking “to taste” and adding a little bit of this and a twist of that as needed, never measuring or referring to a cookbook.

“Sandra’s book instantly made me feel like, ‘This feels like home. These are people I know. People I recognize,’” Clark said.

Despite the challenges of ageism, publishing biases, and cozy industry expectations, Jackson-Opoku joined the ranks of other BIPOC cozy mystery authors, such as Mia Mansala, Valerie Burns, Esme Addison, Vivian Chien, Gigi Pandian, Abby Vandiver, and the late Barbara Neely. She’s done things her way and is happier for it.

“It’s life-affirming and survival-affirming that Sandra did this, [and] did it really well,” Lavin said.

“When I retired from full-time teaching, I just kind of told myself, this is your time,” Jackson-Opoku said. “This is the time to try everything, or as many things as you’ve wanted to try. I’ve always wanted to write for film and television, I’ve always wanted to write a play, and I’ve always wanted to write a mystery novel. So whether I succeed or fall on my face in any of those endeavors, it’s not for lack of trying.”

Tina Jenkins Bell is a freelance journalist, published fiction writer, playwright, and literary activist. Her stories “Kaiko” and “The Avalon Haint” were respectively published in The Overturning (Hypertext) and Red Line: Chicago Horror Stories (From Beyond Press) anthologies. Her play Death of a Marriage is a part of Definition Theatre’s Amplify New Plays program. Bell last wrote for the Weekly in June 2023 when she reported on artist Kee Merriweather’s works’s depiction of a future without environmental racism.