When it comes to legal rulings, incremental change doesn’t warrant big headlines. You can’t say “Building Still Standing,” and you can’t say “Files Not Destroyed.” But what’s often lost in an individual ruling is what could have been—as in, the building is still standing after a wrecking crew was stalled at the last minute. Such is the case in the latest court ruling over police misconduct records in Chicago.

What are potentially hundreds of thousands of files detailing all levels of misconduct by the Chicago Police Department have been saved from destruction. Labor arbitrator George Roumell ruled on April 29 that the files, which date back to 1967, should be preserved at least as long as the Department of Justice’s civil rights investigation into the police department is ongoing. This investigation could take several years.

The files have been the subject of legal drama since 1985, two years after the expiration of the first contract between the city and the Fraternal Order of Police Lodge 7, the union that represents the rank-and file–some 83 percent of sworn CPD officers. And despite Roumell’s recent ruling, the battle for these files is not over.

The central issue involves a stubborn clause in the FOP’s contract with the city of Chicago: Section 8.4, which states, in so many words, that the Chicago Police Department has to destroy all misconduct records found to be “not sustained” that are five to seven years old (the exact length depends on the type of misconduct). For reference, the Independent Police Review Authority (IPRA), which investigates most allegations of police misconduct, finds cases to be “not sustained” about 96 percent of the time, according to a Tribune analysis; CPD’s Office of Professional Standards (OPS), which IPRA replaced in 2007 during a police brutality scandal, ruled “not sustained” 90 percent of the time, a Human Rights Watch report found.

After an appellate court ruled in March 2014 that police misconduct files are public documents, and thus available via the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA), two things happened. First, the Invisible Institute’s Jamie Kalven, the Tribune, and the Sun-Times all filed separate but similar extensive FOIA requests for misconduct documents dating back to 1967. Then, the FOP and the Police Benevolent and Protective Association (PBPA), the union that represents CPD’s sergeants, lieutenants, and captains, both sued in Cook County Circuit Court. The unions hoped to block access to those files on the grounds of Section 8.4. Judge Peter Flynn granted both of the unions injunctions that temporarily blocked the public’s access to many of those documents, and ordered the parties into arbitration. Arbitration is a legal process separate from the courts in which both parties (in this case, the unions and the city) agree voluntarily to accept the decision of a third party. The arbitrations that Flynn ordered would decide the ultimate future of the documents.

Strikingly, before the arbitrators in both the FOP and PBPA cases went on to find in favor of preserving the documents in some way, they both initially delivered decisions favoring the unions. On November 4 of last year, longtime Chicago labor negotiator Jules Crystal issued an award in favor of the PBPA, writing that the CPD failed to uphold the contract when it did not purge old digital misconduct records (notably, though, he interpreted his case as not at all relevant to misconduct files on physical paper). And on January 13, Michigan State University law professor George Roumell, Jr. found that the language in the FOP’s Section 8.4 was too binding. He ordered the city to come up with a list of files it thought specifically should be kept under the law, and wrote that the rest of the files, physical or digital, had to be destroyed.

According to court records obtained by the Chicago Defender, it was only after the city filed to vacate that ruling that Crystal reversed his decision this February, writing that he could not “ignore the fact that the posture of this case is different from what it was when the matter was arbitrated in 2015.” He argued, essentially, that the social and political climate in Chicago had changed enough to warrant a reversal of his earlier ruling. Crystal directed the city and the PBPA to write a replacement for Section 8.4 “that is not inconsistent with court rulings, judicial pronouncements, and/or legislative enactments.” All three PBPA contracts expire at the end of this June.

Further developments also influenced Roumell’s April 29 decision in favor of the city. On Friday, he too issued a complete reversal of his January interim award. The federal prosecutor leading the DOJ’s investigation into the CPD sent letters to a law firm hired by the city requesting that all police misconduct records be preserved. The letter specifically mentioned those records contested in arbitration. This letter, Roumell wrote, directly influenced his decision, as did Crystal’s February reversal. He claims it was against the interests of all parties involved for him to ignore the DOJ’s preservation requests and its ongoing investigation, since that would likely trigger future litigation from the DOJ. His decision was issued a full two weeks after the original due date set by Judge Flynn, which is not mentioned in the decision itself at all. Roumell didn’t return a request for comment.

The Previous Contracts

Previously, the CPD and the two unions have attempted to work this out between themselves. The FOP claims it first became aware of the department’s practice of hanging onto all of its police misconduct records in 2011, when the union’s grievance counsel, Richard Aguilar, filed complaints with the city for not destroying records more than seven years old.

In a letter responding to the FOP’s grievances, CPD’s current director of human resources Commander Donald J. O’Neill expressed his surprise at the claims of the grievances. At the time, O’Neill was a lawyer with the department’s Management and Labor Affairs Section.

“As the union well knows, this practice is the result of several Federal Court orders issued in litigation dating back to the early 1990s involving matters of police misconduct,” he wrote, going on to cite three separate court cases the FOP had been involved with that dealt intimately with Section 8.4.

It’s impossible not to note that the FOP’s grievances came at a time when the movement to make misconduct files public was gaining momentum. As O’Neill noted, it’s difficult to believe that the FOP was unaware of the department’s practice of keeping misconduct files, regardless of what Section 8.4 reads.

There has been a Section 8.4 in every version of the FOP and PBPA contracts since the police department was unionized. In an email, G. Flint Taylor, a civil rights attorney and one of the founding members of the People’s Law Office (PLO), wrote that nearly all of the city’s contracts with the police unions have been negotiated in secret and approved by City Council without debate. Even Crystal and Roumell didn’t know much about the initial negotiation process; as Crystal wrote in his initial decision in favor of the PBPA, “While the…language in Section 8.4 may have been the result of hard fought negotiations and/or a [simple] compromise, the end result is language that is clear and unambiguous.”

Darka Papushkewych, the city’s chief labor negotiator at the time when the very first FOP contract was signed, did not reply to a request for comment. Papushkewych is now general counsel at the Metropolitan Pier and Exposition Authority, which owns and manages Navy Pier and McCormick Place.

G. Flint Taylor and the People’s Law Office

In the case of Monroe v. Pape, the 1961 U.S. Supreme Court ruled in part—after hearing testimony about how thirteen Chicago police officers ransacked the home of a black family with six children, made them stand naked in a room, and arrested the father, holding him for two days on false charges before freeing him—that municipalities were not people. Therefore, the city of Chicago could not be held liable for the actions of its employees—the police—under a provision of the Civil Rights Act of 1875. In 1978, however, the Supreme Court overruled Monroe in the case of Monell v. Department of Social Services of New York, which found that municipalities could be “people” and could be sued for deprivation of rights.

Beginning in the late 1980s, the PLO, an activist Noble Square law firm perhaps best known for representing the family of Fred Hampton, took advantage of Monell. By filing civil rights cases against the city, the PLO was able to make extremely broad discovery requests of the city and the police department. These requests covered both complaint register (CR) files, which detail complaints against police officers, and “repeater lists,” lists of officers known to the department to have a habit of noteworthy misconduct.

The city and department rarely gave up these files willingly, according to Taylor, but beginning in 1991, a series of court orders in federal cases the PLO brought against the city ensured that these files were being produced. More importantly, these court orders preserved the files from being destroyed under Section 8.4 by referring to the portion of the contract that prohibits destruction of records dealing with current litigation.

In a 2002 letter to the CPD, Jeffrey Given, then the city’s Chief Assistant Corporation Counsel in charge of litigation surrounding police misconduct, explained how the PLO successfully stymied the city’s attempts to comply with Section 8.4 by taking advantage of Monell. “Typically, [the PLO takes] an expansive view of this claim and essentially contend[s] that all disciplinary files are relevant,” Given wrote. In a 1991 PLO case called Fallon v. Dillon, federal judge Milton Shadur ordered that all misconduct files be preserved moving forward. Since then, CPD has indeed preserved all the files, though they have not been accessible to the public.

“Surprisingly, at least to me, given the city’s conduct in a lot of cases, they followed those orders,” said Taylor. Indeed, in his fourteen-year-old letter, Given writes that “the scope of the requests makes it virtually impossible not to retain every CR that has existed since the time of Fallon.”

Taylor, who is seventy years old, takes a long view of his battles against the police establishment. “Now it’s 2016,” he said in a phone interview, “and we started in the 1980s, so you could pretty much say we’ve been fighting for thirty years a running battle with the city and the unions for production of these files, for preservation of these files, and for transparency with regards to these files.”

Jamie Kalven and the Stateway Civil Rights Project

In 2001, a decade after the People’s Law Office made significant inroads with the retention of police misconduct files, writer and activist Jamie Kalven and Craig Futterman, a University of Chicago law professor, started the Stateway Civil Rights Project. The project was a collaboration between residents of the Bronzeville Stateway Gardens public housing development, where Kalven was living at the time, and Futterman’s students at his Civil Rights and Police Accountability Project, housed at the UofC’s Mandel Legal Clinic.

The fifth federal civil rights suit filed by the Stateway project was filed on behalf of Diane Bond, a Stateway Gardens resident who along with other residents had been attacked multiple times by a group of white CPD officers, who had claimed to be searching for drugs. Futterman, Kalven, and their students made PLO-style extensive discovery requests in the case, which was designed to reveal background information on how the back-end of how CPD deals with misconduct. Then Kalven, acting as a journalist, filed to intervene in the case on behalf of the public, requesting that the obtained misconduct files be made public.

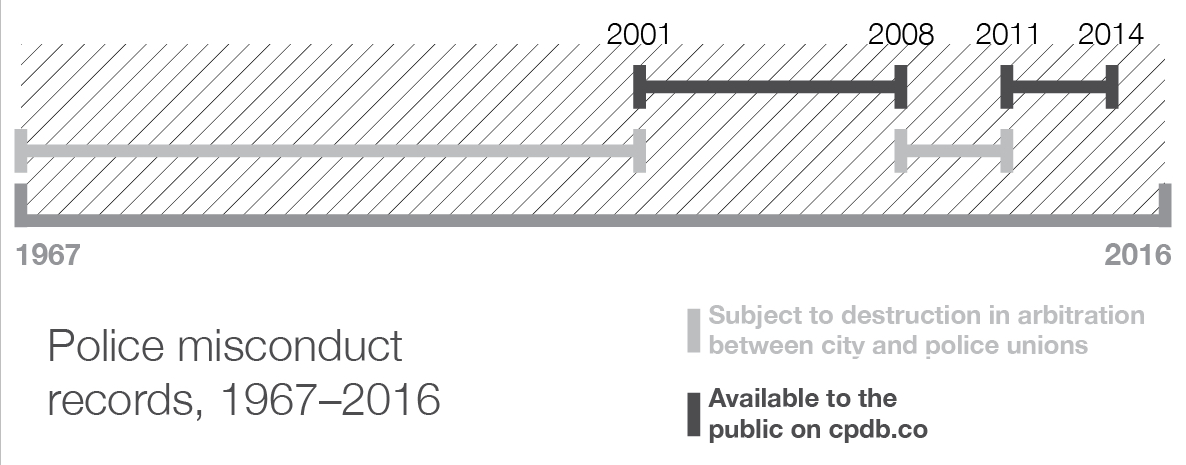

Surprisingly, Judge Joan Lefkow allowed the intervention and approved the request, but the city obtained a stay, or a pause in legal proceedings. After two years of legal back-and-forth, Lefkow’s decision was overruled, but that ruling left the option to file Freedom of Information Act requests to attempt to obtain the misconduct files, which Kalven did. After the city declined to fight the requests in July 2014, Kalven’s team at the Invisible Institute received the data from the discovery requests made in the Bond case. They also received data requested in Moore v. Smith, in which the PLO represented the mother of an eleven-year-old who was beaten and falsely arrested. These discovery requests yielded some 56,000 complaints against over 8,000 Chicago police officers between 2001-2008 and 2011-2014 (data for 2009 and 2010 was not available in either case). With help from some students of Futterman’s, the Institute built a website to house the available misconduct data called the Citizens Police Data Project, viewable at cpdb.co.

What’s ahead

These arbitration awards are not the end of the battle over these documents. Both Crystal and Roumell’s decisions simply keep the records from being destroyed. And though the awards are legally binding, they are also subject to appeal, and both Kalven and Futterman hedged when discussing their merits with the Sun-Times, calling them “sort of a reprieve,” and a “timeout,” respectively.

Both Kalven and Futterman believe that only state legislation can truly resolve the matter, but while there are multiple bills that deal explicitly with the preservation of police misconduct records, none have received their public support. Additionally, University of Illinois at Chicago political science professor Dick Simpson opined that these bills have little chance of being passed in the near future. “Because we are coming to the end of the legislative session with many bills pending,” he said, “including critical budget legislation and many others, it is unlikely, but still possible, that controversial legislation like the police legislation will pass despite the desirability of having laws to protect misconduct records.”

Simpson also sees more obstacles on the horizon stemming from the arbitration awards. Crystal’s decision explicitly instructs the PBPA and the city to reconstruct Section 8.4. The city’s current contract with the FOP expires next June, and if public attention and opinion about the CPD maintains its current scrutiny, it’s difficult to believe the city will get away with signing another contract that includes Section 8.4 as it stands now.

Changing the contracts won’t be easy, however. “The mayor would have to be willing to face a potential strike to change the rules of the existing contracts,” said Simpson. “It is a fight the mayor and the city government should undertake to end both police abuse and corruption, but [which they are] unlikely to pursue when the unions push back.”

A request for comment to FOP president Dean Angelo went unreturned.

This report was produced in collaboration with City Bureau, a Chicago-based journalism lab.