Inspired by C.S. Lewis’ The Screwtape Letters, the Staples Letters are a series of essays in the Weekly written in the form of letters from a veteran teacher, Staples, giving advice to a young teacher, Ms. T. All events in the Staples Letters are drawn directly from real-life experiences in Chicago schools, and names and identifying details have been removed in the interest of privacy. Though fictional in form, the letters are used to address a variety of issues in education, from quotidian classroom considerations to national policy.

You’ve never been to my family’s cabin in Wisconsin, have you? It’s lovely as can be, right on the water. And the nicest part of any trip is watching the sunset over the line of trees in the distance. The sky runs red, reflecting orange and yellow rays through the still water. Each night my mother tries in vain to capture the scene on her phone.

“It’s just…missing something,” she complains, holding her mediocre Instagram photo up to the glorious sunset.

I’ve spent similarly frustrating afternoons at my desk at school, forced to quantify that which resists quantification. I often feel it is my true job to merely produce these phony reams of evidence and documentation, to sharpen my skills not as an educator but as a bureaucrat.

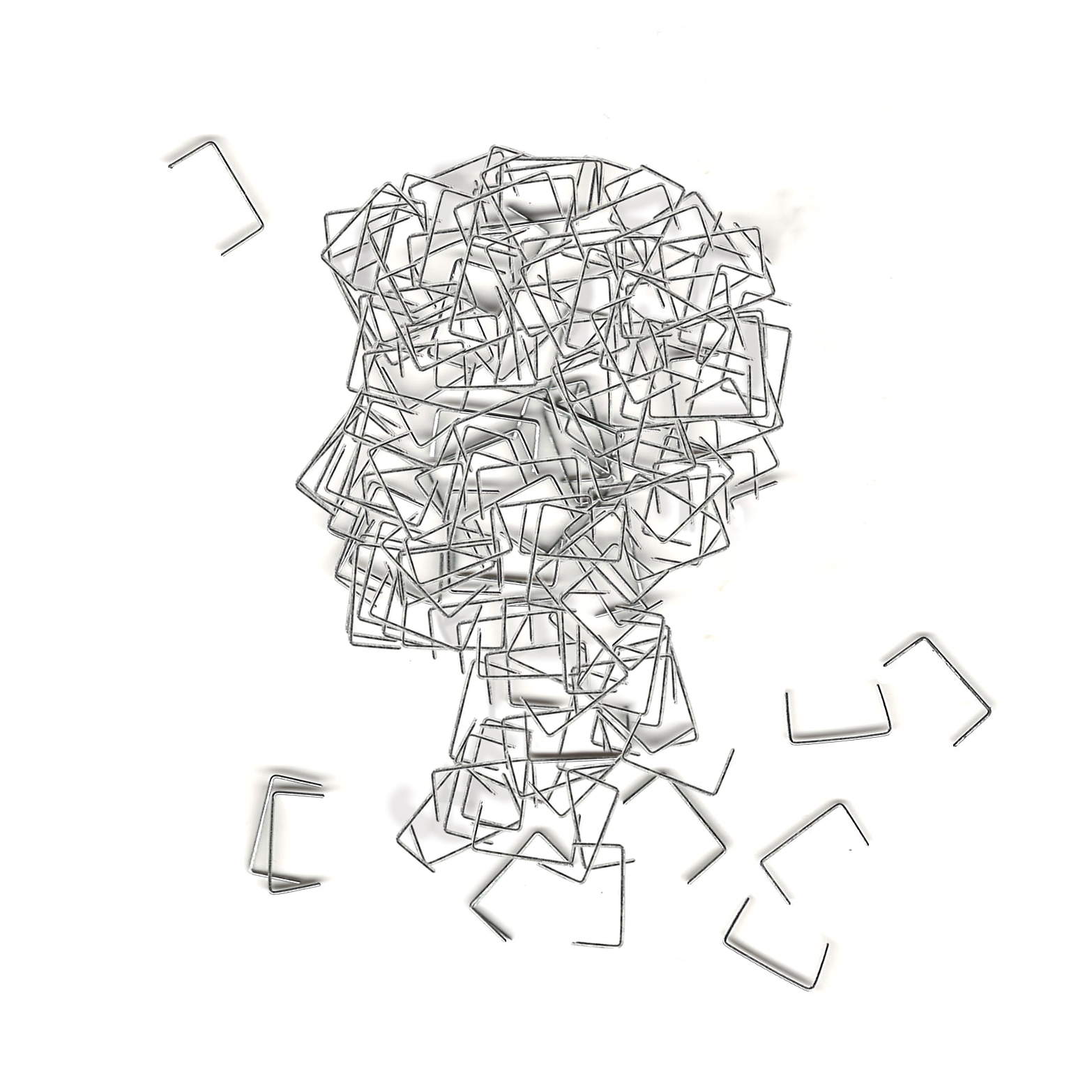

This is part of the business model that has been forced on schools: the massive waste of time and resources dedicated to administration, testing, measuring, and control. For the students, of course, this means all manners of standardized testing, an obsession with rubrics, and all the other policies that conspire to make classrooms such an unpleasant place. For teachers at my school, it takes the form of weekly lesson plans, “modules,” curriculum maps, academic concern forms, and a whole host of other minutiae. Every week, it seems, there is some new piece of data we must create and upload to this or that folder, some new form that needs to be filled out with this week’s chosen jargon. It’s a complete facade.

As department chair, I recently spent a few days observing a bit of every other teacher’s classroom. The admin forced me to evaluate what I saw using some special rubric, that measures dozens of highly specific teacher behaviors. For each, I was to decide whether the behavior was “extremely evident,” “evident,” “somewhat evident” or “not observed” with a corresponding number value for each. Now I ask you: what in the HELL is the difference between “somewhat evident” and “evident”? Are we really to believe the word “somewhat” is a meaningful, objective mark? That one can scientifically differentiate between the two? I pointed out the inherent absurdity and begged them to just consider the long list of observations I’d made. My principal was uninterested—the observations were too subjective. Ah, not like the cooly rational distinction between “extremely evident” and “evident”! You can set your watch to that bullshit.

But that’s just how principals operate. Does yours have the same obsession with verbs that mine does?

See, there are these special lists of verbs you’re supposed to use when designing your lesson plans. The list’s most basic verbs include “identify” or “list,” but the other end of the list has verbs like “create” and “prove” that are supposed to indicate “higher order thinking.”

Principals sometimes take a shine to one list or another of these verbs and demand that every teacher use only the highest end in all their lesson plans. So instead of saying “students will write a short story,” teachers say “students will create a short story.” Transformative!

It’s perhaps a useful thought exercise to look through these lists, but they don’t exist to improve instruction; they exist to improve paperwork. The principal then gathers this paperwork onto their desk, beholds all the pristine verbs, and wipes away a tear drop. “Ah,” they sigh, “my work here is done.”

Until next year. “Our old verbs are out!” they cry. “This is a crisis! A crisis of verbs! We’ve got to use this special batch of new verbs!”

Oh, won’t someone please think of the paperwork!

Like our mandated verbiage, each new initiative comes with the customary sweet talk. Of course, it’s for the students. This is an important lesson, commit it to memory: every evil thing that takes place in a school is for the students—up to and including the closing of the school.

My former principal, however, made the true import of this regime of paperwork explicit. Her favorite expression was CYA: Cover Your Ass, the mantra of the careerist.

It means: don’t actually worry about a problem—just do enough to avoid blame. Make sure you sent the email, filled out the paperwork, made the call. Document everything. After that? Screw it. You’re safe. It means you care enough to keep your job to not be blamed for a problem, but not enough to make sure the problem actually gets fixed. In fact, you’re better off not solving the problem because that opens you up to criticism. It’s everywhere, this attitude, but it’s especially tawdry in a school. When your principal is constantly looking for ways to pass the buck like that, you can be sure your life is going to be miserable. These people are not your allies.

My former principal now has an even bigger, better administrative job higher up in the district. She spent five years vigorously documenting and has been amply rewarded for it. And there are plenty of evil people only too happy to manipulate this paperwork for their own material gain.

Did you see the reporting about Aramark and SodexoMAGIC, the private janitorial services responsible for cleaning the schools? Soon after Rahm awarded the contract to SodexoMAGIC, which is owned by Magic Johnson, he received an enormous campaign contribution from SodexoMAGIC and other companies owned by Johnson. Now, the schools are absolutely filthy, as both companies cut service to the bone. This has been common knowledge among teachers and students for years, of course, and was actually predicted well in advance of the deal.

These companies however, are able to keep this relatively hidden because every principal knew when the auditors were coming and the exact location of the inspection in advance. This made it trivially easy to ensure those tiny corners of the building were spick and span by the time inspectors showed up. The companies were doing a terrible job, but the paperwork said they were doing just fine.

This is the expected outcome when metrics of progress and achievement have no relationship to the real world. The test scores are the authority on what is or is not happening in classrooms; thus the scores become reality. The inspector looks at three rooms in a building, announced in advance, and that report becomes reality, the rat droppings and grime in every other room notwithstanding.

We had a special education audit this year. We knew which students would be inspected well in advance, knew every item on the inspector’s checklist, and so we were able to prepare in just the right ways—special lesson plans were cooked up and a handful of Individualized Education Plans were totally rewritten. One morning we were told all IEP’s absolutely had to be locked away behind our desks; the next week we were told all IEP’s must be clearly visible at the top of our desks. The administration did not recognize these contradictory directions until several teachers emailed for clarification. Eventually it was decided the IEP’s should be visible but there should also be a locking cabinet in every classroom for storage at some later date. Crisis averted.

On the morning of the inspection, a large breakfast was purchased on the tip that this specific auditor loved to eat. Guess what? We passed the audit. Every change that we made for the benefit of the inspector has since been abandoned. Any adult with half a brain can produce the evidence required to avoid scrutiny, just as any private entity can go right on collecting public money indefinitely regardless of the pitiful service they provide.

I said it was my true job to create evidence and paperwork. I’m quite sure I could show Adam Sandler movies three times a week and never hear a word from administration, so long as my paperwork remained pristine.

The actual teaching that goes on in my classroom on a daily basis? That’s more or less volunteer work.

Your affectionate cousin,

Staples