When Jade Mazon reflects on how she persisted through February’s hunger strike to stop metal scrapper General Iron from moving to her home of the Southeast Side, she keeps naming more sources of support: medics from organizations like Chicago Action Medical and Ujimaa Medics who helped strikers manage their health while they demanded the City deny a permit to the polluting company, community members who provided meals for her daughter so she could rest, organizations that checked in on them.

“I never felt community like I did when I was on the hunger strike, and I feel so blessed and energized by it, even all these months later,” she said. “I still had to take care of my daughter, I was still trying to come up with rent money—life did not stop for those twenty-five days. And without that support, I know I personally would not have lasted that long.”

Mazon took part in the month-long hunger strike, which ended with the City delaying the permit for the move. But even without the permit denied as organizers demanded, it was a climactic moment in a much longer fight—one that is still ongoing.

In General Iron’s previous location in predominantly white and wealthy Lincoln Park, it generated multiple environmental violations and years of serious complaints from neighbors about its emissions. When General Iron announced in 2018 that it would partner with another company, Reserve Management Group (RMG), and eventually move operations to RMG’s East Side location, Southeast Siders—and Lincoln Parkers—immediately raised concerns about dumping the shredder in a neighborhood already burdened by industry.

As opposition coalesced into the Stop General Iron coalition, residents were very clear: Moving the controversial shredder to the majority Latinx and Black Southeast Side—less than a mile from two schools, no less—was environmental racism.

Promoting industrial development on the Southeast Side is nothing new. With the Calumet River providing an early draw for industry because of the transportation it offered, the area became a hub for steel mills and factories starting in the late 1800s. As the steel mills closed, City policy kept incentivizing industry to concentrate in the region, designating much of the area as an industrial corridor—the largest in Chicago—in 1995 and zoning most of the corridor as a planned manufacturing district, meant to encourage industry, in 2004.

But the long history of industrial development—and pollution—has also meant a long history of resistance. Environmental justice organizing in the area reaches back to at least 1979, when People for Community Recovery was founded in Altgeld Gardens by Hazel Johnson, whose work to address the high cancer rates in the community and the landfills and pollution contributing to it earned her the moniker “the mother of environmental justice.” In the last ten years, residents have fought with the Southeast Side Coalition to Ban Petcoke, the Southeast Environmental Task Force, and more against harm from petcoke, manganese, and lead.

The campaign to Stop General Iron drew on knowledge from all those fights. Building on the efforts of many others who participated in protests, community meetings, and teach-ins, the hunger strike brought more people to action—the campaign estimates that more than 300 people participated in one-day solidarity strikes—and catapulted the story of a polluter seeking to move to a community already affected by environmental injustice into national news.

Together, the organizers created the conditions that led the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) Administrator Michael Regan to send Chicago a letter raising concerns in May, and led Mayor Lori Lightfoot to announce shortly thereafter that the company’s permit was put on hold pending an environmental study at the EPA’s request. In the city’s first public engagement meeting to share information about its “health impact assessment” on November 4, officials indicated the full assessment will be released by January.

With the General Iron permit delayed, although still not denied, the hunger strikers’ story—and the story of the entire Stop General Iron campaign so far—is one of community power changing what is possible. This summer, we talked to hunger strikers and others who contributed to the fight. Interviews have been edited for length and clarity.

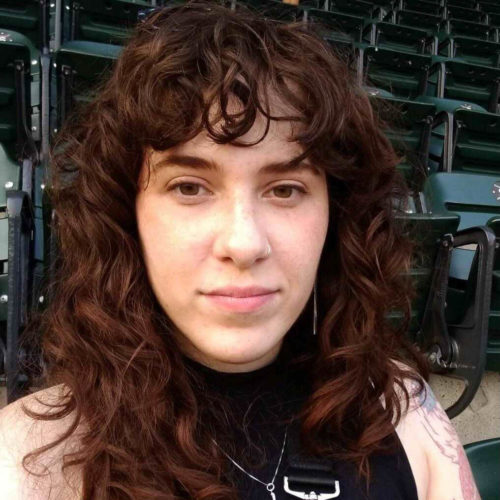

Jade Mazon

Co-founder of the Rebel Bells and member of the Southeast Environmental Task Force and the Southeast Side Coalition to Ban Petcoke

I have been part of the environmental justice community here on the South Side, specifically the Southeast Environmental Task Force, the [Southeast Side] Coalition to Ban Petcoke, and the Rebel Bells. I had been plugged into those organizations already—we were already fighting. This is my third fight, my third company to go up against, but I’m kind of a late bloomer, I’m fifty-one; I didn’t really start getting active till about maybe six years ago.

I was already well aware of the stakes, well aware of the potential for further destruction, further pollution in my community, and when I heard that this was an idea the organizations were floating around, I was all in. I had some experiences with fasting when I was in college, and then I was actually really sick where I couldn’t eat for ten days, I was on IV. I knew that I had gone for periods without eating, so I thought, “You know what, I’m doing this. I know that I can do it. So I am going to do it.” I am older. I am not in the best health. But this is one thing that I could do for my community. And I don’t regret it at all.

[My motivation was] pure frustration. I grew up in the ’80s, a couple of blocks away from the Wisconsin Steel mill, in the ’70s and ’80s. And our neighborhood motto was, “What’s that smell today?” We were just always inundated with toxins in the air, and then in the dirt, and nobody ever checked our water.

I’m not even in it for myself anymore. I’m in my fifties now. Now it’s about my children. Now it’s about all children of the neighborhood—they deserve better than this. When we were kids, we didn’t know that we deserved better. That was never a question for us. That’s what we got, that was our lot in life, and while the steel mill was up and running, everybody had food on the table, everybody had school shoes. Afterwards, it was a different story.

People like General Iron and many other companies figure, this is a great place, that community’s already dead, that soil’s already dead, those people are already dying. They’re a sacrificial zone. So let’s come there. That’s not acceptable to us anymore.

Community is really everything. We couldn’t have done this, we couldn’t have pulled it off, we wouldn’t have had the imagination if so many other communities even outside of our neighborhood didn’t show solidarity and support. You have all these awesome things that money buys, but it doesn’t buy community, and it doesn’t buy health, and it doesn’t come close to our value and our worth. I know it’s hard for me… I have issues with self worth. And I think that’s why I’m fighting so hard for the people who can’t or don’t know how to fight for themselves. I’m just tired of being complacent, and I’m tired of accepting what shit that they give us.

Oscar “Oso” Sanchez

Co-founder of Southeast Youth Alliance and director of Youth and Restorative Justice Programming at Alliance of the Southeast

[The hunger strike] was literally our last resort. This was saying, if this doesn’t do anything, how much do our lives really matter to the City? And that was the beginning of it. When we first started this, we didn’t get a lot of attention. I think it wasn’t until like the seventh day where people were like, “Oh, there’s a hunger strike going on in Chicago.” And then a lot of my friends reached out asking how can we support, and that’s when we asked people for one-day solidarity [hunger strikes]. And then from there, the pain started getting worse; we all talked about it. Because for a hunger strike, [Ald.] Jeanette Taylor emphasized you have to start two weeks, you have to prep yourselves. We didn’t want this permit to go through. So we were like, how can we delay? How can we do something? So a lot of us prepped for a week. And again, the whole month before, we were all thinking about, how are we going about this? How are we preparing ourselves?

I made sure I was prepared to have that conversation [with my family]. They were against it. But they know how I am. I’m stubborn—because you have to be about it, we can’t say we’re going to do something and not care. And if we’re saying we’re willing to put our life on the line, where does it show?

My parents are very spiritual individuals. They were like, “If you do this, you’re gonna have to pray with us.” And I’m, “All right, cool,” let me be with them. So every night, we prayed together.

You know, it was terrifying. The more we went through it, the more I lost weight. And we’re in a pandemic, so it’s hard hugging friends. But I remember when my friends came over to see me, I’d always have a puffy jacket on, and they hugged me. And then they’re like, “Fuck, you’re really going through it,” and they started crying. And I was getting emotional, and my mom was like, “You see? You see how you make people feel?” And I’m like, “But it’s not to hurt you.”

I thought about my community. And I think of my own family. My brother, when he was five years old, he had to be hooked up to a machine at night so he could breathe. He had to do that for five years. I thought about my grandpa. He died in December due to COVID. The doctor said he had weak lungs. And during that time, him and my grandma were sick at the same time. So my grandfather passed away. And we had to lie to my grandma for a week saying, “Oh, he’s just in the hospital,” but we had to prepare for his funeral… They put her on an air tank—the doctor said you can’t breathe that air out there. It’s the accumulation of all the impacts on my family. And being in these town hall meetings, and hearing mothers and fathers cry about how they wanted to live here in this community, and raise their children here and have their dream house here. Then finding that all out and then seeing all the contamination and pollution.

Crystal Vance Guerra

Co-founder of Bridges // Puentes and strike supporter

I am one of the organizers within the coalition. So, it was a decision we all took. How do you organize in a pandemic, during the winter, against such a City-led project? Because ultimately, General Iron had been approved and was given all the green lights by the City despite my community, our neighborhoods saying no.

We had already done petitions, we had already done peaceful marches, we had already done marches at Lori Lightfoot’s house, we had already done all these things. We needed something. And that something was the hunger strike. As an organizer, you never want to put people’s lives at risk. That is the last, last, last, last thing you want to do. Because that’s what we’re fighting for. We’re fighting for our lives.

My role was to help coordinate hunger strikers and medics, to get the medics on board to make sure the hunger strikers had things so they could check their blood pressure, they could check their pulse. Different strips that could measure based on their saliva or other fluids, on urine samples, to make sure their muscles weren’t deteriorating. I mean, it’s very serious stuff, right?

We worked with several [medical organizations that helped]. The main one was Chicago Action Medical. But we also worked with Ujimaa Medics on the Southeast Side. They’re Black-led and they do a lot of trainings, not just for organizing: they’ll give people tools, kind of like what I do, self defense, but they do it with medic stuff. Like, how do you treat a gunshot wound? Giving people practical skills to apply in their every day.

Before we even decided on the hunger strike, we reached out to the Dyett [high school] hunger strikers to let us know how it went for them, what did they learn from it? What were their reflections afterwards, what could have they done better? What were the tricky parts? So learning the history of organizing already about the thing, or whether it’s the issue, environmental organizing, or whether it’s the action you’re thinking about taking—whether it be a march, blockade, hunger strike. Learning about that history, within your own community area, city, and connecting with those people, was really what one, gave us the strength to make it a city-wide movement, but then also gave us the knowledge.

William “KiD” Guerrero

Photographer and friend

I when Oscar was on the seventh day. I looked at his Instagram story. You know when you see your friend going through something like that, that’s not supposed to happen in the first place at all. And to know that he’s been part of an organization that’s been fighting this for years now. It really got to me. And then I was like, maybe I should join. And they were doing one-day solidarity [strikes], and he challenged me to do a one-day. I was like, “I’ll do you one better. I’ll just join you.” So I joined. I had to get prepared, though. They told me to mentally prepare myself. I was that guy that’s like, “Let me join now,” and that was a bad mistake. I should have took a week at least to prepare.

My hunger strike lasted for eighteen days. Really it was bone broth, water, and sugary drinks to get some energy. Gatorade and water. Water is highly recommendable, because we’re made of water. I’m not sure if this includes your diet, but scented candles helped me out a bit.

I seriously thought I was going to die. I lost about fifteen pounds. I lost a lot of sleep. I didn’t want to sleep. I thought if I slept, it would be over, like my body would just shut down.

The line that really stuck out to me was when [executive director of Southeast Environmental Task Force] Olga Bautista said that if they can’t move into the Southeast Side, they’re gonna move into Pilsen. And in my head, I remembered when there was a factory in Pilsen next to a high school. It was polluting our air, and I was waking up with dust on the car. I thought it was normal. And going down the highway on Damen, I thought it was cloud makers as a child. And I thought: That’s nothing, that’s harmless. Then, in high school, I came to realize that was polluting our air. I had some friends with asthma. And it may be that reason. Seeing some of my friends excluded from activities because of asthma, because the air has contaminated the lungs and all that, really made me think like, this is all preventable. This is all preventable. And we’re the generation to stop it.

Local elected officials, they have power to be in the press. [Mayor Lori Lightfoot] could have said something at least. At least address it. She could have really said something on the news about General Iron and the harms that they were doing to the Southeast Side.

If I had the power, I’d move those big factories away from residential areas. They could still work and they could still do their business, but they need to move out of residential areas. Because the air that we’re breathing in from them, it’s not gonna help us in the long term. It will affect us, it will affect us no matter what. But just far away as possible.

Marcelina Pedraza

Activist and union worker

I only did a one-day hunger strike in solidarity with the hunger strikers. Because I wanted to show my support for the campaign. You know, we’ve been fighting for what seems like forever, from toxic polluters moving into our neighborhood. And it seems like no one’s listening. So that’s why we decided to take it to the next level with the hunger strike. And I just knew what I can do, I’m capable of at least spreading the word and showing solidarity by doing a one-day hunger strike.

I’m very involved in my union at work. I’m an electrician. I work in the neighborhood at Ford, actually. I have always been passionate about workers’ justice, and environmental justice. And I feel like they are very related, and they intersect.

I grew up in South Chicago, like on 89th and Exchange. I lived there up until I graduated high school. I was bused out [for school], so I got to see other parts of the city, but then I still came home to South Chicago. I lived in LA for a few years for college, came back and stayed up north. I was in Rogers Park, Humboldt Park. Rents were getting too high. And this was twenty years ago. Moved around a bit for work, but since 2016, I’ve been back on the East Side.

I have strong roots here. My parents were born here. My grandparents came from Mexico like one hundred years ago to work in the steel mills and railroad and all that. So I come from a long line of union workers, but also, I hear the stories of how South Chicago was thriving back in its heyday, when all the mills were running—and it was so polluted, I’m sure. But the neighborhood was thriving, there were businesses and movie theaters, restaurants, and stores. And then after all the jobs left, the neighborhood just saw huge economic collapse.

We first started a COVID Resources Group, a kind of super group of people from different organizations in the neighborhood, just to get resources out to the community, like, “Hey, do you need PPE? Do you need access to testing?” So we started this group, we started this page on Facebook, and it kind of escalated from there. We got connections with other organizations, youth organizations, student organizations, and community groups.

Then with us being the environmental organization, we’re like, “Hey, we’re also doing this campaign against General Iron, are you interested?” We were having meetings once a week, then we had them twice a week, all online, all virtual. And so because we had a huge amount of help from the youth, high school students, other youth-based organizations—they’re big on social media. They were really good at making flyers and would make interactive GIFs, and all these things to post and share and retweet and all that.

Lauren Bianchi, Donald Davis, and Chuck Stark

Teachers at George Washington High School

LB: We had followed it in the news a little bit, I think some science and social science teachers were starting to ask students what they think about it. Once I heard that more community members of different groups were getting involved, I reached out to some activists to find out what we could do. We started meeting as just an informal space, [we] were kind of a coalition, but we didn’t necessarily call ourselves a coalition [yet]. We planned protests. We strategized overall. So for all of us, we didn’t hear about the hunger strike; we actually were part of the decision-making body that decided whether or not we would have a hunger strike.

I don’t think that this campaign and the hunger strike would have looked the way that it did, had there not been a movement at this school to remove the police. Just a few months before, the teachers and students kind of got involved—students wanted police-free school. So those student leaders were confident, feeling really good about that victory, and wanted to win more in their community.

CS: We had just started remote teaching when COVID first hit. So on Earth Day of 2020, I saw a Change.org petition to sign to Stop General Iron. And that’s when I started looking more into it directly. That’s when I took that as an opportunity to teach about it and teach about particulate matter with my students via remote learning. That resulted in one of my students helping present at an end of the year conference about this issue. From that there were other teachers that got interested in it, got involved.

Then, that summer was the campaign to remove our [school resource] police officers, which was successful. Then we had these teachers and students that were empowered by the win to remove the police officers from the school and also understanding there’s another issue to address. So then our energies kind of moved to that. We built a more robust curriculum and the science department, other social science classes, were starting to teach about it. The student voice committee got activated and it became the next fight. All that built up to the point where we realized that we had exhausted every other effort. And so a more extreme measure was needed to make a point.

LB: We had a strategy of escalation as the formal processes failed us. We had always thought at some point, we all might do an arrestable action. We might block the street to prevent construction, and some of us get arrested. But this was during the height of the pandemic before vaccines. And we realized that if we all got arrested, we would be at risk of getting sick. We also thought that we could get slapped with eco-terrorism, and we might not just like get bailed out the next day. So we were like, do we want to risk getting COVID or some of us losing our jobs because we were in jail on trumped-up charges? Olga Bautista from Southeast Environmental Task Force, she was the one that was like, “I think we have to escalate, and I don’t think we can get arrested. I think we need to do a hunger strike.” And we all sat with it for a while.

DD: I would add that there were solidarity strikes, and teachers did a solidarity strike. I participated in the one-day strike, and my family did.

LB: Over seventy educators in the city, and thirty people who work here, fasted for one day. [Chuck was one of the three participants who began the long-term hunger strike.]

DD: I know a couple of students who did a couple weeks each, and they weren’t under supervision of health care, and that was a concern. So that was a big worry we had was that people would use this, and then they wouldn’t take the precautions necessary to look out for their health. And so that was why it took a couple months to plan this, so that the health officials could be consulted.

CS: Change the zoning. Right now it is a planned manufacturing district. So the only thing that can be built on these lands is things like General Iron. That needs to change. There is a lot of open space here that is contaminated, that needs to get cleaned up, that can get cleaned up, and does not just need to be used for industrial use. So change the zoning.

LB: And we’re asking for money for a new high school. We need a new building. We’re overcrowded. And there’s a lot of the same safety concerns in our building that exist in all older buildings. I believe the building was built in 1958. We’re one of the last true neighborhood high schools. The Southeast Side is so disconnected and divided by water from the rest of the city. Where some schools are struggling and being hurt more by charters, we have very strong enrollment, we need a bigger building.

Yesenia Chavez

Member of United Neighbors of the 10th Ward

There are a lot of different components to Southeast Side organizing that work very well and cohesively, and we saw that with the General Iron campaign. I think that’s when it really came to the forefront to me that each individual organization has a really critical role. For United Neighbors of the 10th Ward, one, we had three members [including me] go on a hunger strike. And then on top of that, the environmental racist acts and what policies were broken, what wasn’t—a lot of that was dissected by United Neighbors of the 10th Ward, and then also sustained with drafts for public comment, information on how to register for town halls, advocating for translators for town halls, doing door knocking to make people aware of General Iron.

[It’s important to] understand that you can’t really create and maintain movements like this with just one or two organizations. Even if they’re spearheaded by one or two organizations, the maintenance to upkeep and stay relevant in today’s media is a whole different ballpark.

On the civic level, it’s been a challenge to bring to light a different perspective for our residents, because they’re so accustomed to being neglected politically, you know, misrepresented, right? They’re so used to just getting scraps from the City and performative politics. And then on top of that, there are a lot of immigrants on our side of town. And there is that language barrier, where all the information that we’re gathering in English, political jargon included—we have to make sure that that’s translated, because if not, we’re missing half of our audience.

A big focus of ours was to uplift voices that weren’t heard. To have parents included that wouldn’t always take the mic; to have students included, to have someone that’s taking care of their elderly parent that’s connected to an oxygen tank, that you wouldn’t usually see on the news, but their voice in our community should still be respected… And I think that approach led to a lot of our success.

The different student organizations and groups throughout the 10th Ward were very active in our campaign, very vocal. And it was very nice to see that they came from a place of not knowing what to say, being intimidated, being timid, to—I’m going to cry talking about it because I’m so proud of them—to them leading actions, and them talking about mental health, and them talking about the importance of environmental justice and creating whole programs in their schools. Seeing that the next generation is starting to feel comfortable within themselves to be vocal, to stand up for what they believe in, talk to others about it fearlessly—that makes every single struggle worth it.

Chris King

Communications strategist and friend

My best friend is Oscar Sanchez. And I’ve been watching him go through all these struggles with environmental justice for a really long time now. About a week into his hunger strike, I had talked to my ward Independent Political Organization, 32nd Ward United, and we were going to do a single-day solidarity strike as an IPO to try to raise awareness.

And then towards the end of my first day, I realized I wanted to do it a little bit longer. So I moved it to a full week. So I went on hunger strike for a week. It was really good work, and that’s what kept me going. But like, I was hungry, I was shaking, I was cold. I don’t wear socks in the winter—I’ve never, never ever cold. And I had to buy everything. I was in a full coat in my house.

Before I was on the comms team, they were having a press conference, and I had driven Oscar there, because I tried to help take care of him as much as possible, because I think at that point, he was on day fourteen or something. He was not doing well. Oscar’s not a big dude, but he dropped a lot of weight really quick. So I was just like, hey, I want to be here for you. We’ll drive around, bro, hang out in the loop. And then it sort of got brought on after that.

I helped do social media kits; I helped do press releases. I made a lot of memes. That was pretty cool—it was my favorite part of it. I videotaped. I was all over the place, wherever we needed help communications-wise.

I think our social media kits were probably our most important thing I because we could be loud with people power. One of our social media kits, we were able to get #DenyThePermit to trend, which was a pretty big deal. Because once that happens, City officials are seeing that—and then it went beyond City officials to national government, like the EPA stepped in eventually.

There were people hunger striking as far up north as like the 40th Ward. And before I met Oscar—I moved to the city when I was twenty-three or twenty-four, I had never heard of the Southeast Side until I met Oscar when I was working at Harold Washington College. It was really, really cool to see the city pull together and fight for something together.

Carlos Enriquez

Organizer and strike communications team member

The City and Reserve Management Group—the company that bought General Iron—they saw the relocation as a done deal. And we were committed to say, “No, it’s not over until it’s over.”

We knew that if we fought back and we won—or even if we fought back and got close—that this could be a story that can inspire communities throughout the entire country to actually say that we have a voice and we will be heard when it comes to matters of our health, the health of our families. And so, I think all the while, we knew that this was what it was, this was bigger than just the Southeast Side, bigger than just Chicago, that this could impact environmental policy for the entire country.

It’s not enough to be able to put a cap on how much industry is happening because there still needs to be an effort into actually cleaning up all of the waste and harm that has been brought forth to communities like the Southeast Side by this toxic legacy of decades of unregulated industry.

And so I think that one thing that I hope that we can start doing through this process is a lot of these struggles for environmental justice, by their nature, are defensive struggles: against industry, and against polluters, against policies. But we want to get to the point where we’re able to put forward and fight for a vision of what is possible, like where we’re not just on the defensive.

For folks who don’t live in the community—I don’t live in the community, but I do spend a lot of time there and have made these relationships—yes, these communities have [experienced] an adverse impact, but air is not something that’s stagnant, air goes everywhere, polluted air in the Southeast Side is eventually going to reach the lungs of every single person in the city.

It should be enough to hear the stories of these marginalized communities that are taking it upon themselves to fight for clean air, which should be a human right to everyone, but at the very least, [understand that] the Southeast Side is fighting for all of us, for all of our rights to breathe clean air.

All authors were Summer 2021 Civic Reporting Fellows with City Bureau. Corli Jay is a freelancer from Auburn Gresham whose work largely focuses on Chicago’s music scene and systemic injustice; she last covered Black artists’ pandemic experiences. Ahmad Sayles is a Documenter with City Bureau; this is his first piece for the Weekly. Olivia Stovicek is a senior editor at the Weekly who last reported on public meetings. Bridget Vaughn is a contributor to the Weekly and was part of a team that covered the closure of Robeson High School in Englewood.