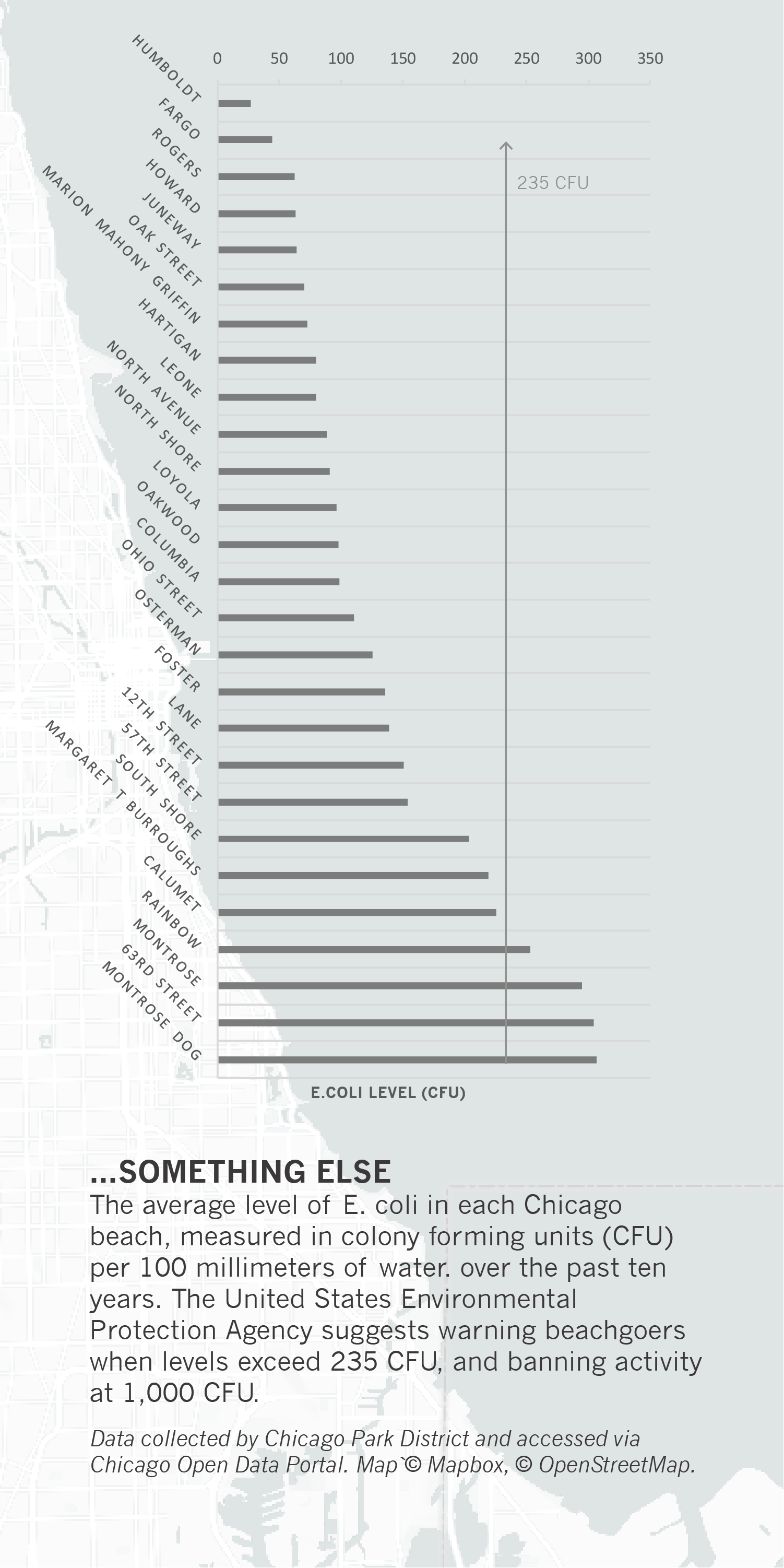

Here’s another reason to use a pooper scooper—when fecal matter from dogs, birds, and other animals flows toward Lake Michigan, waters at the shore can become contaminated with E. coli bacteria, putting a damper on even the sunniest beach day. Seven of the ten most contaminated Chicago beaches are on the South Side, eleven years of recently released data from the Chicago Park District show. According to analysis by OpenCity software engineer Scott Beslow, some beaches in particular—63rd Street Beach, Rainbow Beach at 79th Street, and Calumet Beach—stand out, with over twenty percent of the samples taken at each beach exceeding the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) contamination standard for safe swimming water.

Until last year, the city tracked beach water quality with E. coli bacteria, which flourishes in the gastrointestinal tracts of all warm-blooded animals. Although it exists mostly in harmless strains, some strains of E. coli do cause illness in humans, so the EPA considers it an indicator of potentially harmful water contaminants. When a beach’s bacteria level tops the EPA-designated “exceedance” level—235 colony-forming units per 100 milliliters of water—the Chicago Park District issues a swim advisory for that beach. At this level, eight out of every thousand swimmers could potentially get sick, assuming the E. coli in the water is all from human fecal matter. But Chicago’s beach bacteria comes largely from nonhuman sources, and with animal E. coli, the risk of illness is “unclear,” according to United States Geological Survey scientist Meredith Nevers said.

“I just don’t think the numbers are out there,” she said. “So we play it safe by [tracking] E. coli regardless of source.” Actual rates of contamination-related illness are difficult to track, as they are rare and not easily identified.

The culturing test the Park District used until last year required eighteen to twenty-four hours to get results. This meant that beach managers issued (or did not issue) swim advisories based on results from the previous day. Studies have shown, however, that bacteria levels can vary substantially over small distances and times, and that there is little correlation between bacteria measurements from one day to the next. At one beach, a group of scientists wrote in a 2004 policy analysis, “there is virtually no relationship between the E. coli level on days when samples were taken that exceeded the standard and the E. coli level on subsequent days when the results were reported and swim closures were instituted.”

Chicago’s beach bacteria doesn’t come from any single source, according to Nevers—it comes from various “nonpoint” sources, including birds, dogs, and the stormwater runoff that flows over city streets and sidewalks carrying contamination straight into the lake. “A lot of pollution that goes into the lake—be it bacteria or phosphorus—is actually just running off the land,” she said. “And in urban areas there tends to be more of that. Because it’s so built up, there isn’t as much green space to absorb any rainwater.”

Algae and sand can provide warm, moist shelters in which bacteria can grow, Nevers said, adding to a beach’s bacteria population. And once bacteria ends up at a beach, coastal structure, wind, currents, and temperature can all play a role in determining coastal bacterial presence.

This combination of factors makes addressing the bacteria count at any particular beach a slippery task.

“Not each beach is exactly the same. So to say ‘South Side versus North Side’ is a very inaccurate statement,” said Zvezdana Kubat, a Chicago Park District representative. “Every beach is looked at on a case-by-case basis,” she added.

Nevertheless, the beaches with the highest bacteria counts have historically been South Side beaches.

“The biggest factor has to be the actual physical configuration of several of these beaches,” said Nevers. 63rd Street and Calumet Beaches, among others, have large breakwaters on their southern ends, artificial structures that trap sand and maintain the beach’s form. “Any bacteria that get into that area have a hard time getting back out. The water never really refreshes, because you don’t get that full-lake circulation pulling the contamination away from the shoreline.”

The breakwaters are “sort of a double-edged sword,” Nevers said. “You need to capture the sand, but in doing so you capture any nearshore contaminants as well. So it really is just the shape of the Lake Michigan shoreline.” She said that some North Side beaches that may have to close less often are “street-end” beaches with straight shorelines.

Rainbow Beach doesn’t have a large breakwater, though, and Nevers is unsure why it would have consistently high bacteria levels. “I think there’s some runoff issues,” she said. In 2013, the Park District partnered with the Illinois Institute of Technology to install a stormwater filter at Rainbow Beach. Since then, levels at Rainbow Beach have fluctuated, dropping in 2013 but rising again a few years later. The filter remains in place as the only project currently targeting high-exceedance South Side beaches.

Various other projects, many initiated through the congressionally funded Great Lakes Restoration Initiative, have helped the Park District come at the problem from different directions. One project brought on border collies to chase away gulls from beaches; another involved installing native plants to deter bird activity. A district-wide program called “flight control,” overseen by the U.S. Department of Agriculture, works to control the geese population through spraying grass and oiling nests around city parks.

The Park District also reminds the public not to leave trash on beaches.

“When folks are littering that’s a contributing factor, because it attracts the gulls,” Kubat said. “That’s why we’re asking folks to do their part and not litter. Just as simple as throwing their trash away in a garbage bin is extremely helpful.”

This summer, the district is also launching a new bacteria-monitoring system, in partnership with the University of Illinois at Chicago.

“We consider it real-time testing,” said Carol Kim, who manages beach water quality for the Park District. “We get it in three to four hours.”

Rapid testing was piloted for the past two years at a few beaches, but will be expanded this year to eighteen to twenty beaches. Kubat explained that “some beaches are very close to one another so they only need to take one sample—they’re part of one continuous beach.” The new method uses DNA analysis techniques to measure levels of enterococci, a different bacteria approved by the EPA as an indicator of contamination from fecal matter.

With the new enterococci data, the city is planning on developing a predictive model that will forecast same-day bacteria levels using meteorological data. Although such models have generally been successful, they tend to be less effective on South Side beaches with breakwaters. “Poor circulation locations tend to be much more difficult to predict,” Nevers explained.

Nevers said that addressing the discrepancies caused by the shape of South Side beaches would be a tall order. “Adjusting circulation is a big bill,” she said. “You don’t want to take out a breakwater that’s protecting a harbor, or that’s protecting an area from flooding.”

Did you like this article? Support local journalism by donating to South Side Weekly today.