The popular image of a private all-girls Catholic high school usually evokes ideas of strict nuns, enforced uniformity, and fierce standards of discipline rather than notions of female empowerment. And yet at Queen of Peace High School, many alumnae, students, and even staff members would insist that progressive ideas were the foundation of the school. Again and again, the women I spoke to used the words “feminist” and “voice” to describe the fifty-five-year-old all-girls high school located on a fifteen-acre tract of land in Burbank, Illinois, a few blocks west of the Ford City Mall in West Lawn.

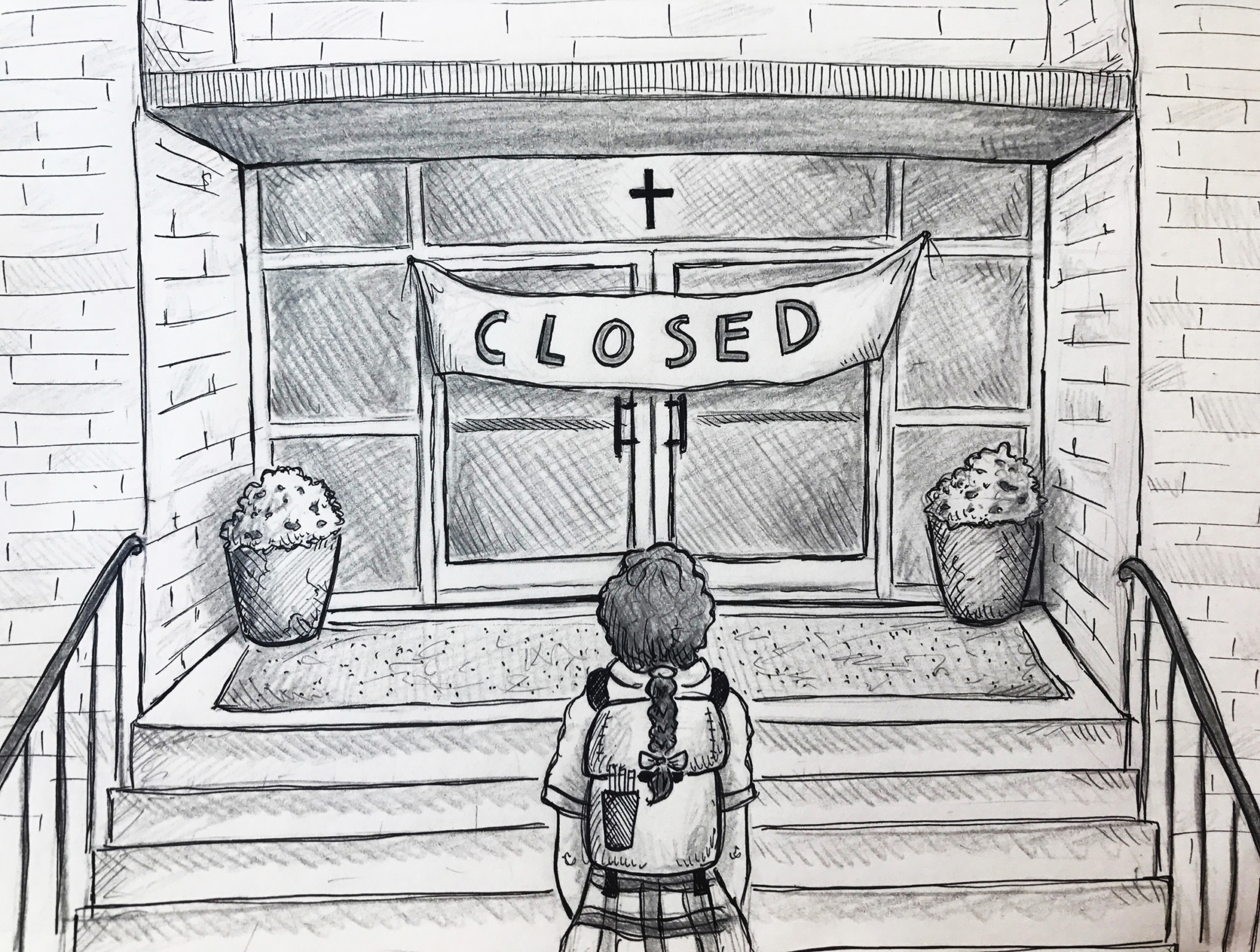

“What they teach us when we go to Queen of Peace is that you have a voice. You have a voice for yourself and for the people who can’t be heard,” said Mary Kate Love, a member of the Class of 2007 who at one point worked as a recruiter for the high school. Since February, Love has been raising her voice as part of a concerned chorus in the aftermath of the school’s surprising and, for many, devastating announcement—come the end of the current school year in June, Queen of Peace will be shuttering its doors for good, bringing to a close one of the last bastions of an all-girls Catholic education on the South Side and Southland.

The decision, confirmed and announced on January 24, took those who had deep affection for the school by surprise. Current students and alumnae were understandably upset at the prospect of the closure—the school was the place some alumnae envisioned their daughters one day attending. In the following days’ news coverage, what emerged was the familiar story of imminent closure—an all-girls Catholic school past its heyday, plagued by falling enrollment and financial difficulties, and forced, finally, to make the difficult decision. It wasn’t an unprecedented trajectory. Similar closures have happened on the South Side to a number of Catholic elementary schools, but also to all-girls Catholic high schools similar to Queen of Peace. In 2013 and 2014, Maria High School and Mt. Assisi Academy, located in Chicago Lawn and southwest suburban Lemont, respectively, had announced their closures in much the same fashion. In a twist of bitter prophecy, Queen of Peace High School had been one of the schools that had accepted transfer students during those closures. Now, it is, ostensibly, looking for other Catholic institutions to do the same.

In the months since the announcement, the high school has released multiple statements offering reasons for the closure and laying out a transition plan for current students. Several family and alumnae meetings have also been held at the school in an attempt to further explain the decision and the community’s way forward. For some, however, questions about the decision to close still linger, as does anger, expressed in vigorous online debate since the announcement.

“A Catholic feminist high school”

Five miles north of the Illinois border in Grant County, Wisconsin, is the spiritual and intellectual ground zero of Queen of Peace—the motherhouse of the Sinsinawa Dominicans, the congregation of sisters and nuns who have been the sponsors of Queen of Peace since its inception and were its first teachers. The Dominican tradition remains the spiritual backbone of the school until now, and is the root of its tradition as a “Catholic feminist high school,” in the words of Class of 2004 alumna Annette Alvarado.

Sister Janet Welsh knows this tradition well; she was one of the first women to set foot in the Queen of Peace building as part of its inaugural graduating class in 1966, and is also the only alumna to have joined and graduated into the order. In her office at Dominican University’s McGreal Center in west suburban River Forest, Welsh talked me through the Dominican tradition of education and the founding of Queen of Peace High School. As one of the earliest members of the school and a trained historian, Welsh’s grasp on both narratives is extensive.

“At that time, there was in the popular mind the idea that women, their constitution, was too tender to study any of the hard sciences. They would have a nervous breakdown or they wouldn’t be able to become pregnant,” she said, laughing.

Those popular beliefs inspired Father Samuel Mazzuchelli, the nineteenth century priest who founded the Sinsinawa Dominicans, to create St. Clara Academy, an all-girls institution that paved the way for more all-girls educational institutions, leading all the way to Queen of Peace.

“When Queen of Peace opened up, almost all of us from St. Sabina [School] went and applied. We took the test. But they could only take four hundred,” Welsh recalled. “I remembered how I was so happy that I had gotten in, but also how some of my friends were put on a waiting list. They went to Longwood [Academy, then known as Academy of Our Lady] in the end, but it was kind of sad that they weren’t going to share in this new adventure of going to a brand new school.”

That was 1962. In September of that year, Queen of Peace officially opened with a class of four hundred freshman girls, a faculty of fourteen, and a curriculum that included religion, mathematics, Latin, and home economics. It was operating out of a wing of the neighboring all-boys school at the time, St. Laurence, as the women waited for the construction of their own school building to be completed. In 1963, with double the students, Queen of Peace moved into the building that continues to house it to this day. In an entry on the school found in the Archdiocese of Chicago Institutional History, the state of the high school two years later was decidedly robust:

“In September of 1965 there were 65 faculty members: 44 Sisters, 21 lay teachers. The school population was 1,579. In December of that same year the certificate of full state accreditation arrived. Queen of Peace had come of age.”

This picture of institutional health, and enormous enrollment, is a stark contrast to the school’s current state, with a mere 288 students. And yet, Welsh insists that while enrollment and funding have waned across the years, the school maintained its unabashed tradition of female empowerment. When asked why she had chosen an all-girls education—particularly one at a school as nascent as 1960s-era Queen of Peace—Welsh explained it was there that students “had the leadership opportunities.”

“Unfortunately, back in the sixties, if you were in a coed school, most of that would have been relegated to the young men and maybe a woman might be the secretary,” she said. “This is the age where feminism nationally [was] just beginning to stir the souls of women in the United States. [With] an all-girls education, you were told you were talented, intelligent. You could do anything if you had the skills and ability.”

It’s a sentiment that’s echoed by alumnae from subsequent graduating classes extending into the twenty-first century—that an all-girls education was instrumental in making them stronger and more independent, and that its growing scarcity was a loss. Alvarado, who described the school as feminist, recalls her time there and how it had “promoted that concept of sisterhood” for her.

“I’m one of four girls [in my family] and it created a level of woman power. Like, you’re a woman and you’re capable of anything. And that was amazing. I noticed how much of it impacted my education when I went to college. I noticed that I wasn’t afraid to speak up in class,” she said, adding, “I’m still friends with some of the St. Laurence alumni and they said about [Queen of Peace students], ‘Man, you girls are bossy, but that’s all right.’”

Despite the appreciation for an all-girls education from Queen of Peace students, a cursory look at all-girls high school options on the South Side and Southland reveals its consistent decline in availability. After the closing of Queen of Peace in June, two options for an all-girls Catholic high school remain on the South Side: Mother McCauley High School in Mount Greenwood, and Our Lady of Tepeyac High School in Little Village. Regionwide, the number improves by just one: Trinity High School in River Forest. For current Queen of Peace students looking for a similar all-girls environment, their choices are few and far between. For example, both Trinity High and Our Lady of Tepeyac—some fifteen and nine miles north of Queen of Peace, respectively—would be a transportation headache for most students.

Pulling from all parts of the City

Many alumnae remember not only Queen of Peace’s female-centric environment, but its atmosphere of diversity and inclusivity—both economically and racially. The sentiment is perhaps counterintuitive given the price of tuition at the school ($10,500 a year), and the long, continuing history of segregation in the South and Southwest Side neighborhoods and suburbs where many of Queen of Peace’s students live. It’s difficult not to think of nearby Mount Greenwood where just last year, a local coed Catholic high school suspended several students for sending racist text messages about protesters demonstrating against police brutality after the killing of Joshua Beal, a black man, by an off-duty police officer in the neighborhood. And yet, Queen of Peace is remembered fondly by its alumnae as a contrasting stronghold of diverse representation—a school that, not bound to a particular parish, drew students from across the city of Chicago and its suburbs.

For alumnae, the brand of acceptance found in the school is unsurprising. It was in Queen of Peace, after all, that Catholic Schools Opposing Racism (COR), a coalition of Catholic schools, was founded in 1999. COR organized collaborations among schools to introduce anti-racism and diversity programming in the Catholic school system. Under the auspices of then-principal Patty Nolan-Fitzgerald, who was also a charter member of the Cardinal’s Anti-Racism Task Force, diversity and social justice education became a more formalized part of the Queen of Peace experience.

Rebecca Hacker, a graduate of the class of 2008, recalls full-day workshops that took place in the school gymnasium where issues of race were tackled head-on. “They would have girls up there asking in certain ways what were ‘race facts,’ or [bringing up] things that you wouldn’t talk about everyday because it might make somebody nervous,” she said, adding that discussion would include topics like skin color and colorism.

“For me, I remember the school being really diverse,” recalled Alvarado, who commuted daily from Little Village to the school when she was attending. “It was a good experience that got me exposed to a lot of other cultures, lots of other faiths. They had this one amazing class where we had field trips to different places of worship. It was the first time I went to a mosque, first time I went to a synagogue.”

Most of the alumnae approximated the school population when they attended as being majority white, including many first-generation Polish immigrants, with significant populations of Hispanic and African-American students. Data from the state board of education shows that the school’s population in 2016 was fifty-two percent white, thirty-five percent Hispanic, and nine percent African-American. What former students of Queen of Peace also mentioned, however, was the strong working- and middle-class background of the student body, regardless of ethnicity.

“I think the impression you get when you think all-girls, Catholic school is like, rich girl. And that wasn’t the case. I mean, we were all middle-class girls from all different parts of the city of Chicago,” said Love about her cohort. The school was and is by and large dominated by students from working-class to middle-class backgrounds, a demographic detail that bears out in the percentage of current students receiving financial aid—sixty percent—and that would turn out to be pivotal in explaining the subsequent fall in enrollment as the years went by.

Alvarado, who received financial aid as a student at Queen of Peace from the years 2001 to 2004, recalls how the school had been particularly generous at a time when finances were strained in her family. She remembers tuition being priced at “four to five thousand” per year at the time, nearly half as much as the $10,500 it is today. The rising cost of tuition soon became evident, however, when it came time for her two youngest sisters to choose a high school. By then, Queen of Peace had ceased to be an option because tuition had become unaffordable. “We just couldn’t do it anymore. Changes had to be made so that the youngest two, even though they wanted to go to Queen of Peace…it wasn’t an option anymore,” she said.

Costs were rising at Queen of Peace, and for some families, beginning to take a toll on their ability to send their daughters to the school.

According to the Archdiocese of Chicago Institutional History, in the eighties, the prognosis for Queen of Peace remained decidedly positive: “In light of the school’s continuing vitality, its stable membership, its innovative curricular and co-curricular programs, and its solid commitment to a Gospel-centered educational process, Queen of Peace in 1981 remains a viable, secondary school alternative to public education for the South Side of Chicago and its neighboring communities.”

What tipped the scales?

A Perfect Storm

In a statement released after the announcement of the school’s closure, President Anne O’Malley pointed to two reasons for the decision: an unsustainable financial deficit, and falling enrollment.

As mentioned, about sixty percent of the students at Queen of Peace receive some form of financial aid to offset the annual tuition, which, O’Malley points out, is already below the true cost to educate a student. The real cost of educating a Queen of Peace student per year is in fact $15,500. The $10,500 charged to students, if all of them paid the full price, meant a $5,000 gap per student that the school was struggling to bridge. O’Malley stated that the figure that would have been required annually to “continue to ensure a quality education” for students was “more than $1 million above-and-beyond tuition.”

“The gap” is not a phenomenon unique to Queen of Peace.

“If you talk to anyone who works in private Catholic schools, they talk about the gap, and how tuition might be $5,000 but it actually costs $7,500 to educate these kids,” said Angela Gazdziak, a former alumna of the school who also worked on fundraising as an employee of the Archdiocese of Chicago at two Catholic schools. In these cases, aggressive fundraising and sources of financing external to tuition, like sponsorship, make up the gap. This method keeps private Catholic schools afloat, but just barely. In the period from 1984 to 2004, the Office of Catholic Schools (OCS) under the Archdiocese of Chicago recorded 148 school closures. More have followed in a seeming epidemic of private Catholic schools teetering on the precipice of closure, of which Queen of Peace is but just one of the cases.

For the Burbank high school however, their trajectory of falling enrollment was exacerbated at each turn by a multitude of factors: an aging demographic in the neighborhood, the closure of a number of “feeder” elementary schools that supplied the bulk of Queen of Peace’s student population, a controversial 2006 ouster of then-principal Patty Nolan-Fitzgerald, the 2008 financial crisis that severely impacted families’ ability to afford a private education, and the increasing competition from charter schools in the area. All worsened the already worrying enrollment at the school, and inadvertently raised costs for each student as the same operational costs now had to be paid out of fewer student tuitions, further driving down enrollment in a vicious cycle.

Sister Colleen Settles, a councilor of the Sinsinawa Dominican congregation and part of the corporate body that approved the decision to close the school, told me that the Board of Directors had been aware of the state of falling enrollment and financials several years before it became dire. They had been working on a five-year strategic plan to turn the school around. The 2014 introduction of a science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM)-centered curriculum, which included courses in engineering and biomedical science, for instance, had been part of that plan to make the school more attractive to prospective students.

“We were in, I think, year three of that strategic plan and knew that it was not producing the results that we had hoped for. That’s why they went to the STEM or STEAM program, which included the Arts, and [changed] the curriculum, in order to attract the students who would make the school more viable. But that wasn’t working,” Settles said.

“We knew that if we kept the school open any longer, it would totally take away our ability to help the girls transition to other schools through scholarships,” she said of the decision to close. “We wanted to have enough reserves to be able to give the scholarships that would help them go to their next school.”

And that’s what the school is focusing on now: a transition plan. For the 288 students who currently attend Queen of Peace, all will be headed to other institutions after this year, either to college for graduating seniors, or other high schools, with most of the students, according to O’Malley, choosing to transfer to schools within the Catholic school system. In February, the all-male St. Laurence High School next door announced plans to become coed and accept current Queen of Peace students in fall 2017, and other girls in fall 2018. For the faculty and staff, some of whom have been at the high school for decades, attempts are underway to prepare them for retirement if they choose, or to support them in new teaching positions in other schools.

“People are doing their best to support education, particularly Catholic education, but you can see around us that there have been over forty schools that have closed since 2000,” said O’Malley. “So I don’t believe anyone’s blowing the market and saying that if you come and help us, we will stay open. We know the percentage of our population that gives back to Queen of Peace and they’re very generous, [but] that percentage could not turn it around. It’s statistics.”

The Catholic school system continues to face closures across the city. For alumni of Catholic schools like Love, an adequate response to the situation seems urgently lacking. “I’ll tell you right now that more [schools] are going to close in the next five years,” Love said. “It’s just going to be a matter of who.”

“I’d love to see an integrated response to what’s happening with our school system in general. Because [the Catholic school system has its] problems, but CPS does too,” Love said, referencing the public school system that in some cases has emerged to replace closed down Catholic schools, occupying those same school buildings. For her, the loss of Queen of Peace is not just a personal blow, but is implicated in the larger issue of what she sees as narrowing educational options for students, where the void left by closed down Catholic schools is left either vacant, or filled by vulnerable public school options, struggling with their own state and local financial troubles.

“The education system in Illinois is prime for a shakeup,” she said. “So what’s a sustainable solution look like for the state of Illinois? I don’t know, but I know that there’s got to be an answer.”

As Queen of Peace prepares to shut its doors, the latest in a wave of Catholic school closures, the questions linger: What now for the Catholic school system? And, who next?

Did you like this article? Support local journalism by donating to South Side Weekly today.

I think it’s a very narrow minded article. You clearly only listened and projected the staff who are directly responsible for failing the students. Did you bother to look into the bigger picture? They wanted to close that school and funnel the students and the reserve funding ALL into their wealthy Trinity;) St. Laurence stepped in to assist these students and families who were absolutely devastated and humiliated by the these same women you appear to be commending for a “valiant effort”. Almuni have been fighting to get these students transferred with as little trauma as possible AND are partially responsible for St. Laurence opening its doors to the girls. These women you are praising actually tried to prevent it on behalf of their beloved Trinity. It’s obvious you did research all of the facts. You dismissed the facts as “anger” on the part of the students and their families. What a shame….and a fallacy.

How about Our Lady of Lourdes high school at 56th St. on the southside of Chicago.

You forgot Lourdes HS in West Elsdon

I am saddened by the lack of Catholic education for our young girls in their teen years.

There is no lack. There is a lack of an all girls school, that is all.

Closing a school is a tramatic experience for the faculty and staff because the know that the students and families will feel the ramafications more than anyone else. We are closing their home away from home. We dramatically affect their future. Changes like death, divorce, moving and adding to it the stress of ending another comfort zone is challenging. For many it is their first

DEATH and it is painful.

All the staff can do is to ride out the storm and maintain the strong educational program for them. Share with them all the good they have done and that they will take those memories and skills with them where ever they go in life. Encouraging them to be strong and build on the treasures you shared together.

We also need to understand that the affects of the closure is just as tramatic for the staff and the parents. Anything that hurts those we love like the death of a special person or place lasts forever.

Personal experience in these events is relived each time it happens again. With the threat of our home parishes closing now it makes the divide wider….

God bless these young ladies, their families at home and at school as they move forward. I commend the founding community in helping with the transition and using their funds to help as many as possible remain in Catholic Schools or help those going on to public schools to be prepared for the future.

This article doesn’t answer some basic questions – for example, why is it that Queen of Peace is closing and not Mother McAuley? Why is St. Laurence continuing to operate (although apparently not as an all-boys school any more, having opened their doors to QoP girls)? Yes, the demographics are poor, but they’re also poor for St. Laurence and Mother McAuley. Yes, the economy has been miserable, but so has it been for St. Laurence and Mother McAuley. Why Queen of Peace?

I am a Queen of Peace alumna as well…I had a teacher there who told us not to live our lives thinking we would find a man to take care of us. I thought that was awesome. Just because we went to Catholic school most definitely did not mean we weren’t taught to think for ourselves–that was the first place I ever was. I learned to question things and make educated decisions. So I am sad to see it go for sure…

Insightful article provides explanation concerning the economic & cultural changes on the Southside of Chicago. Sad that Queen of Peace is closing but hopeful that the merge with St. Lawrence will allow a Catholic school option for middle class families.