The Independent Police Review Authority (IPRA) has been called ineffectual by critics since its beginnings in 2007, when it replaced the Office of Professional Standards as the body responsible for investigating serious misconduct and police shootings by officers of the Chicago Police Department (CPD). In response, IPRA has launched several programs over the past six years that it claims have resulted in significant improvements in its performance. According to Larry Merritt, IPRA’s Director of Community Outreach and Engagement, the percentage of cases with “positive findings”—cases with enough evidence to come to a conclusion—rose from about thirty percent to about fifty-three percent from 2009 to 2015, and the percentage of cases with “sustained findings”—cases with enough evidence to justify disciplining officers—rose from about four percent to about twenty percent. Additionally, Merritt argues that despite the criticisms leveled against IPRA, its percentages of “sustained findings” are “not that low” compared to other parts of the country.

But according to some who have previously worked at IPRA, these figures obscure the agency’s shortcomings and suspect practices.

“It is all just a numbers game,” says Lorenzo Davis, a former IPRA supervisor. “People looking at the numbers don’t know what is actually going on at IPRA.” Davis, a former police officer, was allegedly fired by former IPRA head Scott Ando for purported anti-police bias. He argues many of the programs launched by IPRA over the years were part of a conscious effort to improve its statistics. “The numbers might look good,” Davis says, “but [those programs] sacrifice the quality of investigation.”

IPRA’s annual reports explain that when complainants file allegations, they first go through a review process with an “Intake” group. Then, first-hand information is gathered from those complainants who submit a signed affidavit swearing their claims are truthful. If no affidavit is received, the case is closed. IPRA says this program improves the initial reviewing process and directs limited resources to cases with sufficient evidence to make a conclusion. However, Davis says, this practice is often exploited to reduce IPRA’s caseload. According to Davis, the investigators no longer actively seek the complainant’s signature for their affidavit and try to close the cases as quickly as possible. In fact, in IPRA’s 2014 Budget Statement to the City Council, it attributed its improvements in case resolution partially to the introduction of new practices, including the streamlining of investigations through the 2011 creation of a Rapid Response team of investigators. According to the statement, the Rapid Response team is charged with working with the “Intake” group to “close out cases more efficiently and much quicker.”

Nathaniel Freeman, another supervisor who left IPRA in 2011, agrees with Davis. “In the past, if need be, investigators would go out and knock on the complainant’s door to ask for an affidavit,” says Freeman. “But now the complainant has to first make an appointment with the investigator, take time from their work, and come all the way down themselves. Sometimes the investigators would not even be available or ready to take statements after a person traveled to the office.”

If a complainant does submit an affadavit, IPRA assigns one or a team of investigators to canvass the field and gather any related evidence. This evidence is then put into a file and reviewed by another investigator or a supervisor. In this transition, Davis claims, much of the evidence is often not properly communicated, which gives rise to seeming contradictions and gaps in complainant statements. “They will then close the case as ‘unfounded,’” says Davis, “when, at a lot of times, they do not review all the evidence, nor interview the officers before they make the conclusion.”

The experiences of one IPRA employee, who spoke to the Weekly on the condition of anonymity, seem to corroborate Davis’s claims. In the summer of 2013, the source allegedly received a series of instructions from an investigation coordinator and a supervisor regarding changes in IPRA’s investigative procedure. According to the employee, the two allegedly ordered all members of the staff responsible for the intake of complaints about officers to “not ask” complainants any detailed information about the officers they accused or injuries resulting from the incidents in question. “If the complainant volunteered the information,” the source recalls being told, “just write down basic information. Leave out eye color, facial hair, hair style, color, wavy or straight, et cetera. Leave out detailed injuries in the incident.” The source was told that case investigators, instead of the intake group staff, would gather this detailed information later on in the investigative process.

The source refused to follow this order and claims that because the details were missing in initial reports, cases were wrongly assigned to the Internal Affairs Division, a department of the CPD that disciplines officers’s minor infractions, and had to be reclaimed by IPRA later. The source says these details are crucial information, without which investigators are either unable to identify officers or unable come to proper conclusions on cases. As a result, complaint cases can be unjustifiably closed due to “insufficient evidence.”

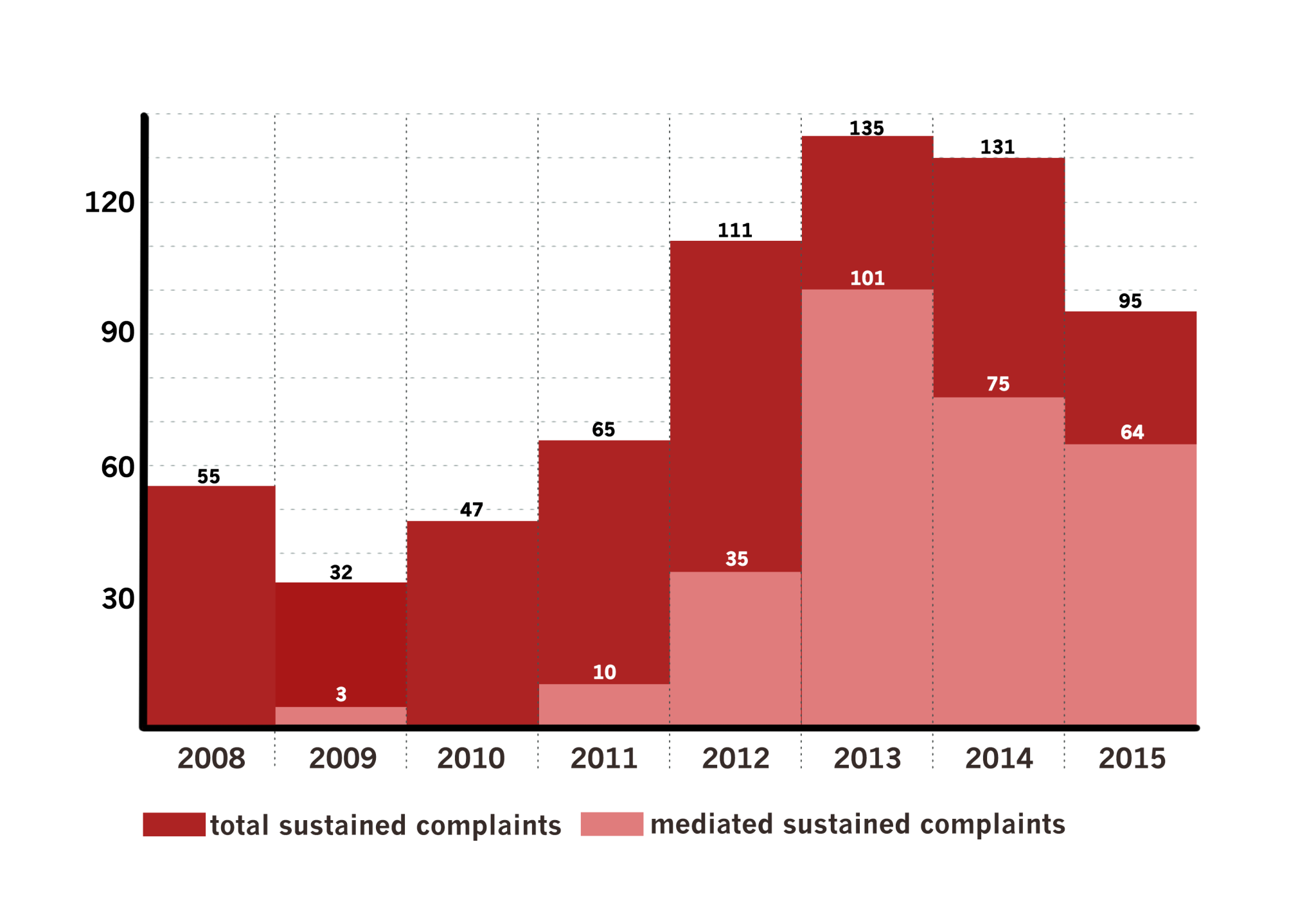

Mediation, a process which, according to an IPRA annual report, “allows an officer to take responsibility for his or her mistakes and reach an agreement with IPRA on an appropriate level of discipline,” is another one of IPRA’s key practices. In 2015, over half of the cases IPRA sustained were settled by mediation. According to Larry Merritt, mediation helps IPRA close cases more efficiently when officers are willing to accept responsibility for their actions. However, this practice may also bolster IPRA’s rate of sustaining cases while protecting officer interests. If there are multiple allegations against an officer from one incident, all of those allegations are assigned a log number that represents the case. Davis says that through mediation, IPRA is able to sustain part of the allegations, often the minor infractions with light penalties, while dismissing other more severe charges within the case as “not sustained.”

“In the process of mediation, the officer, an FOP attorney and an IPRA attorney are brought into the meeting, where they negotiate which of the allegations would be sustained until the punishment is light enough for the officer,” says Davis. “The complainant is completely excluded from the process, not even notified.”

Merritt responds that IPRA’s mediation is an administrative process, not a trial. Therefore, the presence of complainants is unnecessary. He also justifies the frequency of light penalties in mediation. “The purpose of penalty is to educate, not to punish,” he says. “If the officer admits the mistakes and accepts the punishment, he is willing to change.”

Paula Tillman, another former investigator at IPRA, disagrees. “What IPRA does should not be termed ‘mediation,’ but a plea bargaining, a process they use to negotiate punishment in court,” she says.

According to both Tillman and Freeman, mediations in other cities across the country are vastly different from those in Chicago. “The practice[s] of mediation in both New York and San Diego let the officer and complainant sit down and have a face-to-face conversation,” says Freeman, recalling his visits to other public agencies for police accountability. “Only in that sense [is] the conflict is truly resolved.”

Davis and Freeman also allege that deliberate acts further corrupt IPRA’s procedures.

“Findings have been changed, files have disappeared or been stolen away,” says Freeman. “If you refused to change your finding, an administrator of higher position could step in and change the finding.”

The Weekly’s source also alleges that administrators not only censor and control findings, but also silence investigators who question the system and try to speak out. The anonymous source says that after these investigators refused to follow their orders and tried to report the sabotaging of work or documents being deleted or changed by coworkers, IPRA threatened them with termination. The source typed up their complaints and submitted paperwork to the city’s Department of Human Resources, but no one responded.

This is the system that Sharon Fairley entered. Fairley was appointed by the mayor as IPRA’s new chief administrator after the resignation of Scott Ando on December 6 of last year. Ando left his post in the wake of the Laquan McDonald video release on November 24. Tasked with rebuilding IPRA, Fairley has promised to bring independence and transparency to the agency. In early January, she proposed a set of reforms that included introducing new administrative and legal leadership, strengthening IPRA’s legal oversight by assigning legal attorneys to work with individual investigators, hiring a new community outreach coordinator, and publishing the details of investigations on a case-by-case basis.

But it is still unclear whether these reforms could bring substantial change to the agency given that its issues, critics say, are systemic, evincing both a lack of discipline and a pro-police culture throughout the agency.

For Nathaniel Freeman, IPRA’s problems lie not only with its leadership but with personnel on every level. “A significant number of the people who work at IPRA have ties with the police department,” he says. The Weekly’s source agrees: “Many of them have no prior experience in criminal investigations and are not provided with formal training after being hired,” they said. “A lot of people don’t even know how to write a report. Most of them only follow what they are told by the supervisors. This is what makes those illegal obstructions possible.”

Davis also believes Fairley’s reforms have not yet struck the root of the problem. Ill-founded investigation design and practices, Davis argues, can only be effectively addressed after a reorganization of personnel. “Ms. Fairley has not had a chance to make reforms,” he says. “To be successful, her reforms must include removing Scott Ando’s old regime.”

Craig Futterman, a professor at the University of Chicago Law School who specializes in litigations related to police accountability, agrees with Davis.

“Simply changing the top leadership will not guarantee independence and change,” he says. “The problem is deeper than one person.” He commends Fairley’s intentions but believes her potential influence is limited. “I admire the intentions of Ms. Fairley and I believe she will do everything in her power to improve investigations,” he said, “but she is inheriting an agency steeped in institutional bias.”

Nor did Fairley’s promise immediately evoke confidence among the public. Ted Pearson, the co-chair of the Chicago Alliance Against Racist and Political Repression (CAARPR), has little faith in IPRA’s transformation. CAARPR is an activist campaign calling on the city to eliminate IPRA and replace it with an elected Civilian Police Accountability Council. Pearson believes Fairley’s reform can only bring temporary improvement.

“As long as IPRA remains under the Mayor’s office, it cannot be truly independent,” Pearson says. He also questions the fundamental structure of IPRA and its limited authority in the system. “If IPRA can only make recommendations of penalties to the police superintendents, if it has no power to directly fire or discipline the police officer, [then] it has no actual power in bringing changes to the Police Department,” he says.

Futterman, on the other hand, sees the existing hierarchy as necessary. He believes that by limiting IPRA’s authority and placing the ultimate jurisdiction in the CPD, the current structure holds the superintendent accountable for officer supervision and discipline.

“The superintendent should bear final responsibility for discipline [to the officer], not IPRA,” says Futterman. Regarding the possibility that this system would allow the superintendent to overlook IPRA’s recommendation and contain the officer’s misconduct, Futterman stresses the importance of transparency. “To ensure the superintendent’s accountability to the public, the Department must also promptly publish the Superintendent’s response to IPRA’s disciplinary recommendations and his or her reasons for any departures from those recommendations,” he says. “Transparency breeds accountability.”

But that’s only one of several reforms IPRA needs in order to become qualified for its role as the overseer of the CPD. “What IPRA needs is, first, a leader who is as much divorced from the politics as possible,” Futterman says. “The process of selecting and replacing leadership should be independent and transparent, and the process should include voices from the community. Second, its budget and resources must be politically insulated. A good leader is not enough. He or she must have the power and resources to hire qualified personnel and train them accordingly.”

Futterman is currently working on potential legislation to enhance the agency’s independence by ensuring its financial independence. For him, it comes down to one answer: instead of redeeming its old structure, the agency needs to “start fresh.”

Merritt says that many of IPRA’s practices, including mediation, are currently under examination, and also says that reforms of investigator training are underway. Additionally, IPRA is currently creating a new position that focuses on analyzing its performance and improving public access to its data.

But after eight years of dubious statistics, the Weekly’s anonymous source remains skeptical. “Talk is cheap,” they say. “Action speaks louder than words, louder than numbers.”

Additional research by Davis Tsui