A road,” the writer Isak Dinesen observed, “is the fixed materialization of human longing, and of the human notion that it is better to be in one place than another.” South Wentworth Road, then, is the fixed materialization of the notion that one should be able to mosey freely between the South Loop and Chinatown. The Red Line obligingly stops at Cermak and Wentworth every few minutes, doing a great service to several thousand longing, notion-ful commuters every day of the year.

Just one block over, construction is well underway on a new Cermak stop for the Green Line, which runs loosely parallel to the Red through the heart of the South Side. This station will be open by year’s end according to a mayoral press release, and will be almost entirely sheltered by a clearish tube. It is the fixed materialization of Mayor Emanuel’s notion that tourists who are going to conventions at McCormick Place, or staying in its hotel, should be spared that treacherous block’s walk to the Chinatown stop. Nor should they be left vulnerable to a chill while awaiting their train—not if Emanuel and fifty-million TIF dollars have anything to say about it.

One long block. Not quite a quarter-mile’s walk, and not a half-bad one, either. On one side, an innocuous teacher’s college; on the other, a solemn scrum of sturdy and modular senior housing high-rises. Fifty-million dollars for a quarter mile’s convenience works out to ten-thousand dollars per foot, or ten million for each minute of walking. If Rahm cashed his fifty million in singles, and laid them in a stack, they would exceed the distance between Cermak Red and Cermak Green. Why build a station when you could make a little sidewalk out of money and have some left over to boot?

The city’s press release does little to mask that the station exists for the sake of the convenience of well-off: convention-goers and the patrons of the glamorous new hotels and venues that, according to Emanuel, will soon spring up to create the so-called Motor Row Entertainment District. There is talk of a brewery. Cheap Trick considered opening a theme restaurant.

No one has bothered to explain why this is the first “L” station to offer substantial protection from the elements in a city thrashed by winter five months out of the year (except transportation commissioner Gabe Klein, who inventively described the high-concept cocoon design as a “necessity” born of the limited space available).

The only defense of the Cermak Green Line is that it splits the difference in the two-and-a-half mile gap between Roosevelt and 35th-Bronzeville-IIT. That’s the largest gap in the whole system except for one gap out in the western hinterlands of the Blue Line. Another argument holds that eliminating a five-minute walk is precisely the kind of baby step that will coax a few more car-reliant Chicagoans under the CTA’s raggedy umbrella, and so serve the greater good. Maybe—but one would be excused for wondering how many participants of, for example, the Annual Meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncologists, will be eagerly loading up Ventra cards at Jewel-Osco, Cermak stop or no Cermak stop.

These days, municipal elitism and warped priorities aren’t cover stories; they’re the mayor’s vital signs. But a little further reflection will show how a station like Cermak, on a line like the Green, in a neighborhood like the South Loop, all for people who don’t live here, adds up to something much more than a station. It is a richly symbolic project, a distillation of what Chicago was once struggling to be and what has now sprung up in its place.

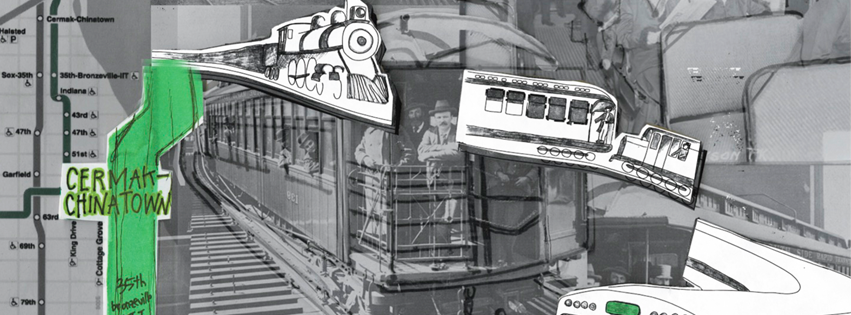

One hundred and twenty-two years ago this fall, a steam-powered wooden train full of inspectors and civic dignitaries plied its way along a four-mile track. This would not have been particularly scandalous but for the fact that the track was two stories off the ground, running over a back alley from downtown Congress Street to 39th. It stopped at such destinations as 33rd, 29th, and 22nd (today known as Cermak Road, after the Czech-born mayor). Such was the dawn of Chicago’s “L.” History is oddly silent as to how the train attained that height. Granted, at that time, the city would have been full of people who remembered the entire downtown being lifted up on jackscrews, pulling Chicago up out of the mud that threatened to swallow the young city.

After only a year, the train was ferrying thousands of sightseers to the World’s Columbian Exposition in Jackson Park. Its route expanded on the original spur by continuing south to 63rd Street, above which it proceeded east to the door of the fairgrounds.

By its sixteenth birthday, in 1908, the newly electrified route had sprouted a total of five branches, each curving gracefully away from its central trunk to serve a terminal region: Englewood, Normal Park, Oakland, and the Union Stockyards, in addition to Jackson Park. It was not a line but an entire system, spreading freely and busily throughout the South Side, several steps ahead of similar developments on the North and West.

For sixty years—through two World Wars, two World’s Fairs, a Great Migration, a Great Depression—the trains kept shuttling along these paths. Today we see service on a fraction of that trackage, at a fraction of the stations. One explanation for this startling decline is simply that population dropped off. Under-patronized routes were axed. Hence, the empty, raised tracks that now snake through Oakland near 41st. Hence, the bridge which does not quite cross the Dan Ryan around 40th, falling short of the east bank like a cartoon cliff. Hence, the hulks of go-nowhere track that loomed over Woodlawn for decades before they were finally demolished. In the latter case, it can be convincingly argued that the change was actively pushed for by a few certain people (CTA scrooges, UofC administrators, an influential pastor), and did not reflect a lack of travelers who would have used the service had it been maintained.

Whatever the cause, it was only well after the rise and fall of this little empire that the first Mayor Daley inaugurated a new breed of Chicago transit: a train running in the median of an interstate expressway, the newly built Dan Ryan. This was realized by poaching funds from one Lyndon B. Johnson, funds that had originally been earmarked for another politician’s similar Northwest Side project (today’s Blue Line). “Mr. President,” complained the man who had lost out, “what is the Dan Ryan?” “God damn you,” said the president, “I don’t know. I just got a call, and [that’s where] it’s going.”

“It” was, and remains, a strikingly different vision of the urban train, as impersonal and technocentric as the earlier model was intimate and homey. It’s all business, stopping infrequently and delivering you not to your home or a restaurant or nightlife, but to a crummy depot where you wait for a bus to take you the rest of the way. It has the ambiance of a carburetor.

Of course, while the Dan Ryan line grew into a workhorse, the proud old “L” continued aging. The 1970s and 1980s brought further consolidation, including the closing of the Cermak station, deemed redundant. The 1990s brought a round of threats to raze the whole system to the ground and replace it with buses. Public outcry was sufficient to bring about overhaul repairs, which closed the line for years, culminating in an anticlimactic and diminished reopening in 1993, at which point CTA implemented a new color-coding policy. The joining of the Dan Ryan line to the State Street subway and the terminus at Howard made the new Red Line the artery it remains today. The term “Green Line” finally entered the lexicon, too, when the South Side “L” was matched to the Oak Park line running due west from the Loop.

With these changes in place, many an armchair city planner has glanced at the CTA map and uncovered the terrible secret of the Green Line’s supposed redundancy.

The Green Line is, or was, for the people. It was a fixed materialization of the belief that Chicago’s widespread masses had at least a measure of human dignity, and that this attribute ought to be reflected in the public works provided to them. To be quite clear, Chicago was never a workingman’s paradise. Indeed it is famed for a unique brand of grisly industrial misery. But the lesson of, say, Sandburg’s poem “Chicago” is not that we Chicagoans are a fortunate lot; it is that we are simply here, and legion, and awesome to the extent to which we are willing to be here, living in columns and rows.

Just a glance at an old map of the Green Line will tell you that it was not designed to provide the most lucrative, the most efficient, or the most utilitarian service. It was a business, certainly, but more than that it was an appropriate, even deferential response to Chicago’s people. Sending out its tendrils right and left, tapping small pockets of life, plunging directly past houses and boulevards instead of concealing itself in heavy rail corridors and no-man’s-land, it extended a broad invitation to a minor miracle: riding a train to work, and riding it back home.

Look also for this spirit in Daniel Burnham’s 1909 Plan of Chicago, which explored the principles of built environment that could best support a graceful, wholesome, and mobile lifestyle for a population of millions. Look to the Lathrop Homes in Lincoln Park to see what was once considered appropriate for the city’s less fortunate. Look to the concentric rings of parks and boulevards, miles afield, and the more you do, the less the city’s glitzy center seems to matter.

And so the decline of the Green Line followed the decline of this way of thinking. At some point public services became grudging favors. At some point it became absurd to suggest preserving an aging institution or making an effort to beautify its replacement. At some point the chief preoccupation of City Hall became non-Chicagoans, and what they read about us in the paper, and how they could be enticed to come visit for a week or two, thus providing the money so desperately needed to, well, build new enticements. Whisk Emanuel back a hundred years (an attractive but irresponsible proposition), show him that the greatest ambitions of the city once radiated outward to the edges, not inward to the core, and his first impression would be something in the spirit of “pearls before swine.”

You can still experience bits and pieces of the finery that used to be typical of Green Line stations. An old ticket booth has been preserved across the street from the Garfield stop. Waiting at Conservatory-Central Park feels like hanging out on somebody’s wraparound porch. Most of the Lake Street houses are still fancifully Victorian: folks really knew how to gable back then. The new Cermak cocoon presents a stark contrast. Its only kin is the Morgan stop, which also opened on Emanuel’s watch, also serves a posh district, also cost a truckload, and is also very, very shiny. This technocentrism is yet another thumb of the nose to the friendly, domestic old Green, which spread so organically across the land.

The changes now in progress in the vicinity of the Cermak stop are shaping up as Emanuel’s architectural legacy. And what a legacy: a neighborhood fit for a NATO summit, engineered to house, court, and entertain exceptional people on whose trickling benevolence the city is presumably supposed to grind its way into the future. Being the grand plotter of streets and the layer of land should be a mythical job that we all envy. A little imagination in that position goes a long way. Emanuel’s imagination, meanwhile, was at one point occupied with how to bring the Super Bowl to a Chicago February. It’s at times like these you just want to give the guy a hug, tell him not to get his hopes up, and perhaps buy him a ticket to that World Cup in Qatar. With mayoral elections fast approaching, one remembers the indisputable benefit of the Cermak stop: it’s a rotten feeling, wishing we could get off the train we’re on, and it’s nice to have plenty of chances.

A possible new addtion to CTA’s “L” System seving the South Lakefront Corridor — the CTA Gray Line: http://bit/ly/GrayLineInfo

Corrected address: http://bit.ly/GrayLineInfo