On August 19, 1955, nineteen-year-old rodeo cowboy Walt Garcia shot and killed another man in Elko, Nevada’s city dump. From that day until his death in 1999, Walt spent the majority of his life in prison: he was paroled seven times, but was always readmitted promptly (usually within a matter of months and never longer than two years). Walt is the inspiration for “LÁLDISH,” his daughter Noelle Garcia’s new exhibition at Ordinary Projects. The description of the exhibition consists of an email exchange between the artist and the Nevada Department of Corrections: “The only information I have is as follows.” On the record Walt Garcia is no more than one violent crime and six instances of recidivism.

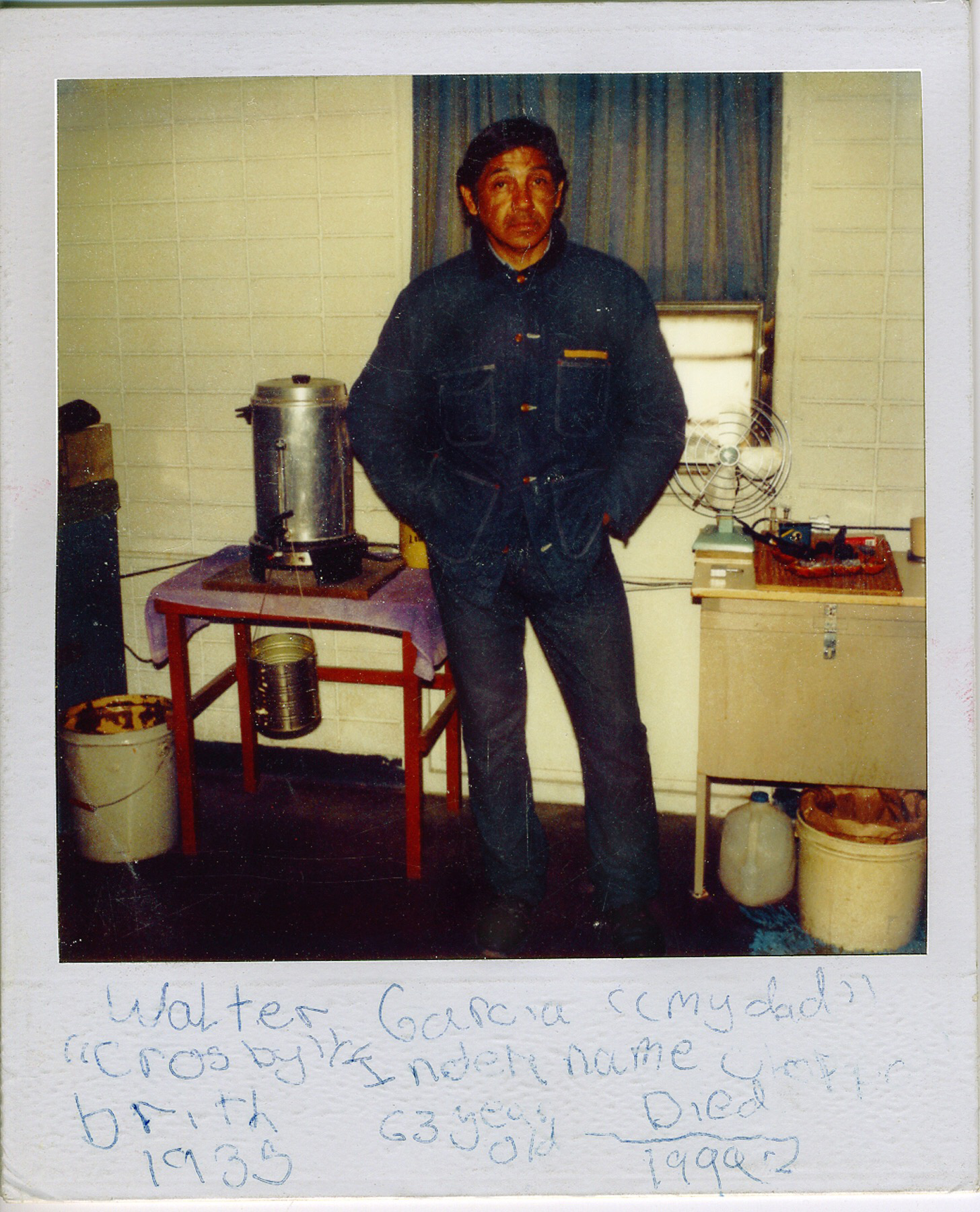

Beyond the official documentation, Walt’s existence is just as fleeting. There are a few dozen blurry Polaroids and his children’s distant memories of a few visits to the prison yard. And as Noelle makes painfully clear, these unofficial records are slowly, quietly disappearing. The first thing she showed me was a candid photo of a group of men: she identified one man wearing a cowboy hat as her father. The decades since the photograph was taken have faded his shadowed face into an impenetrable black silhouette. As I struggled to distinguish facial features that were simply no longer there, Garcia told me that she couldn’t remember her father’s face herself.

Garcia is a member of the Klamath tribe through her father, and though she spent part of her childhood on a reservation, she has always maintained ambivalence toward the traditions of her cultural heritage. “LÁLDISH” finds Garcia coming to terms with two obscured heritages, familial and ancestral, presences that exert undeniable force on her own history and identity even as they recede from view and factual interrogation.

As a young artist, Garcia disdained “traditional” Native-American craft methods in favor of canvas painting: she wanted to be an artist, not a Native-American artist. As she matured, however, she realized the necessity of confronting ancestral techniques, not to brand herself as an artist-of-color, but as a meditation on a cultural legacy that many Native people willfully shun, as her own father did when he used cowboy tropes to define himself.

Her beaded “Stapler” follows the tradition of beading one’s own mass-produced commodities—lighters, wallets, bottle openers—to personalize them. In Garcia’s case, the beads (picked to be as “gaudily ‘Indian’ as possible”) render her industrial stapler, which she used to pin stretched canvases, entirely inoperable. In effect, the traditional personalization defies her former desire to claim independence from one tradition by substituting a second (Western painting). The trajectory of tradition, though, is jumbled by the history of beadwork. Despite the stereotypes, glass beads were introduced to Native Americans by Western settlers, and the distinctive characteristics of American beading did not emerge until after colonization: participation in this tradition is far from a straightforward engagement with a “pure” ancestral heritage.

Another colonial export, tobacco, was first cultivated in the Americas and was used for ritual purposes, but its sixteenth-century popularization in Europe bears no small pressure on the oppression of Native people over the following centuries. In the present day, Cigar Store Indians, American Spirits, and the extreme prevalence of tobacco use among Native-American men (greater than any other demographic group) suggest that smoking, while not a point of pride, is in some way distinctive of Native-American culture. Garcia’s glass beaded cigarettes, scattered in a pile next to “Stapler,” bear witness to this complex interrelationship, but they also emerge from a much simpler impetus: the artist wanted to improve her beading technique, and a cigarette was the perfect shape for repetitive practice.

These familial and the cultural histories explicitly converge on the exhibition’s centerpiece: a fake leather jacket covered entirely with beer bottle caps. Native-American women traditionally make jackets of the sort for their male relatives, and Garcia thought the bottle caps appropriate for a jacket dedicated to her father, a prodigious drinker. In a performance which she will repeat on May 30, Garcia dons the jacket and dances the only traditional dance she remembers from childhood: one, fittingly, dedicated to the dancer’s deceased relatives. It is at times an awkward production, and its ungainliness is not something Garcia tries to hide.

Garcia plans to continue to practice her dancing, like her beadwork, as a way of connecting with her father, her ancestors, and herself, but as she develops she is content with her imprecision. In its concern with process rather than perfection, Garcia’s dance exemplifies the main conceit of the show: the past, distant or immediate, is not simply a given to be discovered through historical research but a body of practices repeated and reinterpreted through time. And even in the absence of fact, engagement with traditions and faces in the shadows lays a strong foundation for the constant reproduction of personal and cultural history.

Great story – amazing art. I use staplers like the one pictured often and relate to this piece – the idea that the beading makes it more beautiful but less useful is also interesting to think about. .. or what if you did use it – the beads would pressed uncomfortably into your hand as you squeeze – maybe they would break under the pressure. . . love.