Onstage, a man was delivering a stream of words and a woman translated his words into a stream of movement. Together, real-estate developer Peter Levavi and dancer Stacy Patrice composed a marriage of language and body, as if to symbolize the union of two phrases on the screen behind them: “ethical” and “redevelopment.”

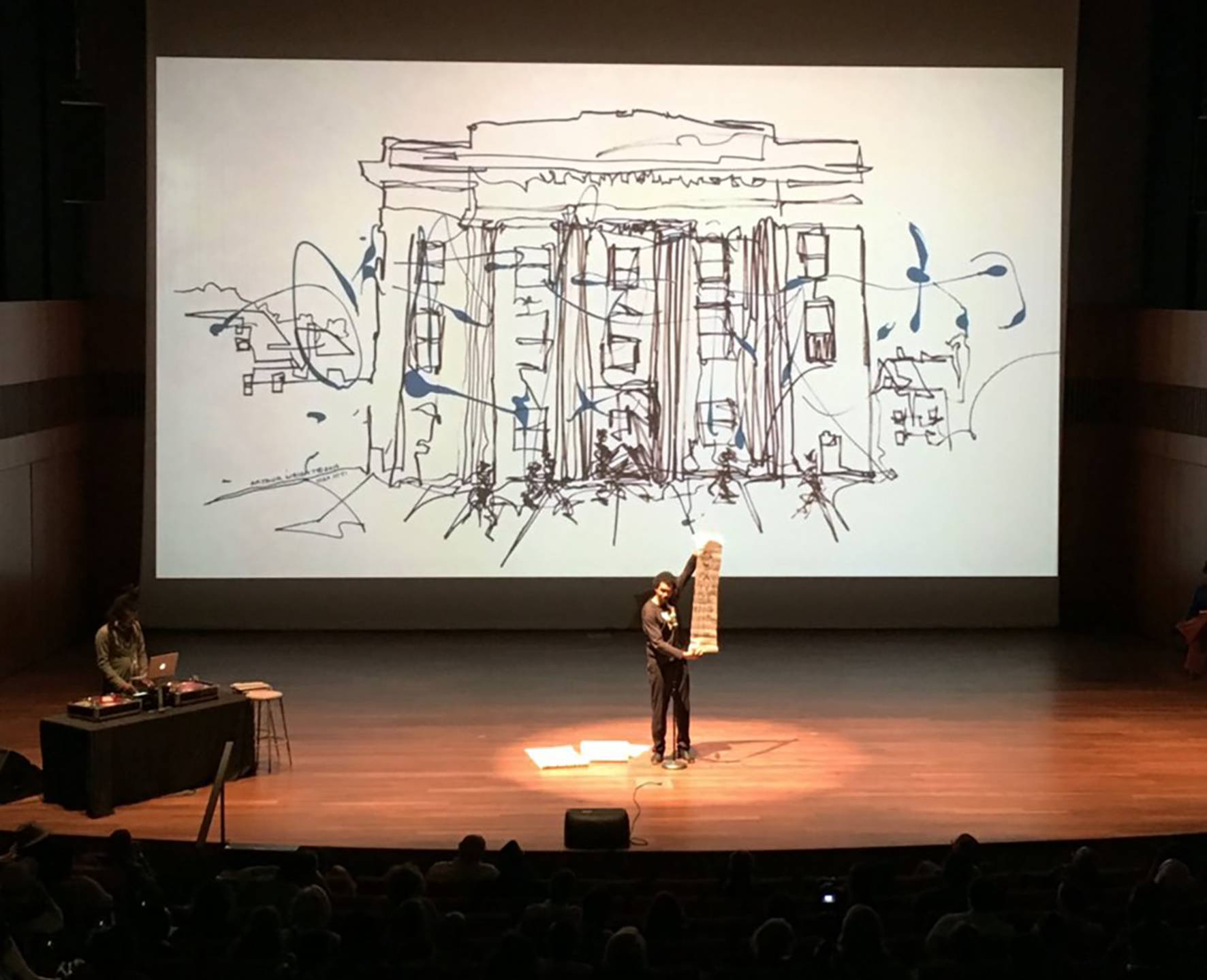

Their performance was one part of an hour-long banquet of poetry, dance, and music at the Logan Center for the Arts on June 22. Several Chicago-based artists, from the Rebirth Poetry Ensemble to Chicago Youth Poet Laureate E’mon Lauren to the musician Coultrain, gathered at this “public convening” to anoint the birth of Ethical Redevelopment, “an evolving set of principles drawn from artist-led, neighborhood-based development work happening on Chicago’s South Side,” as the first page of the event booklet says.

“Ethical Redevelopment is both a strategy and a programming series,” says Lori Berko, the Chief Operations Officer of Place Lab. “As a strategy, it demonstrates how one can shift the value system from conventional financial practices towards community-led, conscientious development that involves artists, neighbors, and other organizers from the community.”

The Place Lab, a partnership between the University of Chicago’s Arts + Public Life initiative and the Harris School of Public Policy, founded in 2014, is “a think tank for cultural transformation,” in its leader Theaster Gates’s own words. In 2014, in response to a request by the Knight Foundation, the Place Lab launched a research project to codify practices in Gates’s famed urban redevelopment work, most of which is corralled under his Rebuild Foundation: Black Cinema House, Dorchester Art + Housing Collaborative, the Stony Island Arts Bank, and more. After conducting a year of interviews with participants in Gates’s projects, Place Lab came up with the concept of Ethical Redevelopment, which consists of nine principles—or, more precisely, catch-phrases—each working toward ethical urban planning. “Repurpose + Re-propose,” for example, advocates repurposing available yet overlooked resources and assets; “Engaged Participation” stresses engagement with neighbors and locals; “Constellations” calls for building ecosystems of diverse talents. Simple and easy to remember, the principles themselves are reminiscent of a self-help guide.

Their familiarity is intentional. “The concepts themselves are not innovative. They are simply underutilized,” Berko said. “People are doing this type of work all over: in Gary, in Detroit, in Akron, in Miami. They are facing issues common to most post-industrial cities, like safety issues, increases in population and poverty, and general problems across the board,” she said. “What the Place Lab tries to do is to elevate, demonstrate, and magnify those who are doing this type of work and get those who may not think about some of these principles, such as traditional developers and financial institutions, to understand and hopefully change their mind about public policy.”

But how is Ethical Redevelopment going to convince for-profits to sacrifice their interests for conscientious urban intervention? Carson Poole, Place Lab’s project specialist, explains that Ethical Redevelopment does not aim to market its philosophy to everyone outside its circle, but rather to targeted groups. He compared development to the beer-brewing industry: “There are some people doing it in the old-fashioned, time-consuming way, where quality, and craft is privileged; some people do it in a high-profit, low-quality way. Every business chooses their own mode of operation based on their motivations. You just have to find the right group of people.”

To attract the right groups of people, one must broadcast as loud as possible—or s seemed to be the philosophy of the convening, which felt at times like a product launch. The crowd burst into thundering applause and cheers as Quenna Lené Barrett, the event’s emcee, saluted the audience in her shimmering outfit.

“I love Theaster Gates’s style of presentation,” a woman in the audience said. “They are not boring or dry like usual policy panels. They always have music, arts, and great speakers—feels like a big party.”

That’s just what Gates and Berko intended—the convening was designed to be interactive and highly theatrical, though what follows is less so. “The public convening will be followed by nine monthly private workshops where we invite practitioners from all over the country to learn about the principles, as well as an online forum and two film screenings,” said Berko. “But we think the convening makes a good introduction.”

The panel consisted of three acts: first, several local poets, musicians, and artists were invited to create original performances in reaction to the principles of ethical redevelopment; next, five academics and community organizers spoke about their understanding of ethical redevelopment. Among them, UofC professor Cathy Cohen and Charlene Carruthers, the national leader of Black Youth Project 100, both endorsed a black, queer feminist approach to urban development. The event concluded with a Q&A session between Gates, Steve Edwards, the executive director of the UofC’s Institute of Politics, and audience members.

The attendees, many of whom took notes during the speeches, were mainly professionals, artists, and graduate students; perhaps a handful were residents from nearby neighborhoods, many of whom had to take time off from their jobs to attend the event, inconveniently scheduled from 2pm to 5pm on a workday.

“I had to tell my boss that I was sick so that I can come here,” an audience member from Bridgeport said, laughing. “But it was worth the effort.”

In contrast, an audience of local residents showed up to the kickoff of a programming series at the Black Cinema House on Sunday, June 19. The 2015 documentary screened, 70 Acres in Chicago, tells the story of the Chicago Housing Authority public housing project Cabrini-Green and its transformation over the past twenty years. Once home to thousands of African-American residents, Cabrini-Green was torn down to make space for new mixed-income neighborhoods, a well-intended experiment gone awry in practice. The documentary argues that the renovation displaced many original Cabrini-Green residents from their homes into the South and West Sides of Chicago, only to be barred from returning to the area because new requirements demanded that residents have a clean criminal record.

In-depth and provocative, 70 Acres in Chicago uncovers the complex dynamic between class, race, and urban spaces. e struggles and conflicts it brings up are also Ethical Redevelopment’s central questions: How can one avoid the cycle of another Cabrini-Green? How can one navigate urban redevelopment ethically and conscientiously within an existing web of interests—public, private, and local? These questions were brought into discussion afterward, where participants shared stories and opinions about the redevelopment work within their own neighborhoods. Many were worried about being displaced in the future. Only around twenty participants were present, but the conversation grew organically, one story building off another, as everyone jumped in. The conversation recognized the severity of the present problem and of collective need for change, but explored little in the way of future soluions—and people who spoke seemed to feel ill-equipped to act, often turning to present Place Lab employees for answers.

At the end of the discussion, people exchanged phone numbers and cards.

“You never know when you might need them,” said one of the participants, a Washington Park resident.

“You know, I think some of [generating new possibilities in the community] is just about asking for cards, cellphone numbers, or email addresses and followed up with something like: you said something that really touched me, I would like to talk more about it,” Gates said at the public convening. “I think it all starts there.” His words resonated with one of the speakers, Carruthers, who spoke about a civic movement stemming from a dance studio. Perhaps the seed of a new movement was planted in Logan Center that day as well, since the public convening is intended as a platform to give rise to new “Constellations” and opportunities. Gates said that he wanted a space to freely communicate with everyone and offer himself “as a target of critique.”

“We know that the UofC has a nice, 474-seat performance hall,” Gates said, “so can we do something with it?”

This place represents so much possibility and hope,” says Brooklyn Sabino-Smith, who works at the front desk of the Stony Island Arts Bank. “Having world-class art exhibitions in a neighborhood where it is even difficult to find a grocery store. Simply thinking about it gives me thrills: What change will it bring here?”

Since its opening last October, Stony Island Arts Bank has become one of Gates’s most well-known projects on the South Side. Not surprisingly, it is also the site for the upcoming private monthly salons in the Ethical Redevelopment series. Located on 68th Street and Stony Island, the Arts Bank serves as both a public arts venue and an archival house—and perhaps most importantly as a space that can evoke new faith in the community’s potential. The success of the Arts Bank, in Gates’s vision, will ultimately attract the economic investment that Greater Grand Crossing and the surrounding area need. When the art thrives, the groceries will come—though reality shows that this vision is still a ways beyond the horizon.

Even on a Saturday afternoon, the Arts Bank can be unexpectedly quiet. One can hear footsteps echoing through the empty corridor. Sabino-Smith said that sometimes she can sit for hours without anybody showing up.

“I think the neighborhood still needs time to psychologically accept the building,” Sabino-Smith said. “The bank has been closed for so many years, and it just reopened last October. Everything is still in the process of planning. As you can see, we haven’t even decided what sign we are going to use, though somebody suggested a giant neon sign.”

Neon sign or not, Greater Grand Crossing has certainly begun to register their presence. “One day we were crossing a street a few blocks away from the Arts Bank, and a traffic guide greeted us and asked, ‘You guys work for Theaster, right?’ I guess we just gave off a different vibe from others of the neighborhood,” Sabino-Smith said. A while ago, she stopped wearing her flowing, artistic clothes to work. She and her coworkers, she realized, are in some way living billboards for the Arts Bank, representing an alternative lifestyle to many in the community.

Despite the occasional hours of emptiness, the Arts Bank’s calendar is constantly filled with events, all designed to engage with locals: a House Tea ceremony and Friday Disco for residents to come and relax after work, writer’s workshops and library access, group cataloguing activities and home movie screenings, all of which help foster a sense of belonging in community. The Bank also employs people from the area. In many aspects, the Arts Bank’s organization faithfully reflects Ethical Redevelopment’s principles, though to succeed in practice it needs to take a few more strides.

Sabino-Smith says the Arts Bank is still seeking to collaborate more with the local community and to make its name known to neighbors. Over the past few months, the Arts Bank has increased its programming and opened up more of its resources to the public. Rather than trying to impose itself on the neighborhood overnight, the Arts Bank follows Ethical Redevelopment‘s instruction “Place Over Time” and patiently cultivates the root it implanted. “We have a very intricate relationship with the neighborhood, so we must be very careful in how we navigate it,” Sabino-Smith said.

Despite the efforts of projects like the Arts Bank to present themselves as inviting, some in the neighborhood are skeptical about the possible effects of any development. Participants at the Black Cinema House screening worried about displacement, while one audience member at the convening asked how redevelopment could avoid gentrification.

“Gentrification is an internal conflict in Gates’s development strategy,” says Clare Wan, another attendee at the convening, and a UofC grad student who studies the South Side’s informal economy. “Any top-down development work that attempts to stimulate local economy through arts and culture can theoretically lead to gentrification. If they succeed in bringing in new investments, it inevitably raises the home prices and will force out those who cannot afford the rent.” She questioned how much Gates’s projects and the new investments he expects can provide income opportunities to locals.

Meanwhile, the workshops that will be occurring in the Arts Bank won’t include residents’ voices, though the conversations will eventually be published online. The private workshops’ participants include representatives from arts and development nonprofits and from traditional real estate companies, from the Chicago Housing Authority and similar government agencies across the country. In part, that’s because Ethical Redevelopment is not a program intended for the general public, but for professionals and policy makers.

This exclusivity points to a larger problem underlying the Arts Bank and Gates’s other projects. While the Arts Bank provides a generous number of programs and resources to the locals, it offers them neither the power nor the autonomy to demand those resources they are most in need of—nor is it intended to. The exclusiveness of Ethical Redevelopment workshops hardens this line between the benefactors and recipients, a line that also prevents Gates and his team from fully integrating into the community. But one question always remains: Who will really benefit?

Gates is not unaware of these questions: indeed, he posed them to the public on June 22. “When is the moment that the resources in a place can be solicited by the people who live in the place and then given access directly to those resources? Because the resources are consistently coming from somewhere. And who are the people that manage and administrate those resources? I think we need as much policy to govern that,” Gates replied to one audience member’s question. “Why can’t the poor [directly] organize?”

Gates explained that a third-party administrator like Rebuild Foundation is necessary in guiding the under-resourced. “There is a lot of fear when the poor realize the amount of injustice put on them and begin to rebel. There is a systematic attempt to put that off,” he said. ”We know that it is a sincere cry from the masses, it is just an undirected cry….I think there is a way in which we have to begin this radical love and joy, radical organizing and emerging work [through a third party’s platform].”

So that work will begin at the private workshops at the Arts Bank. “We want people who participate in the monthly salons to really get at the meat of the project,” said Berko. “Part of the goal is also to re ne the principles of Ethical Redevelopment. These principles are not set in stone—we want others to opine, to challenge, and provoke us. We are learning at the same time as others are learning and sharing.”

We must put the most marginalized at the center of the table,” Cathy Cohen said at the June 22 convening. “A few hipster cafes will not make the problem go away.”

During my visit, I passed by the area where the Stony Island Arts Bank plans to set up a bar that serves wine, beer, and other refreshments. One has to wonder: will the Arts Bank become little more than a “hipster cafe” that allows residents from up north to visit without encouraging them to venture further into the South Side? Or will it become what the principles of Ethical Redevelopment promise: a place that fundamentally empowers an under-resourced community?

Another initiative combining arts and urban renewal was announced a few weeks before the Ethical Redevelopment convening: the UofC’s plan to expand its cultural enterprises in Washington Park, building a new “Arts Block” adjacent to the Arts Incubator, BING Art Books, and Currency Exchange Cafe. Some of these arts spaces are, or will be, housed in vacant buildings, former grocery and liquor stores, amenities that are scarce in the neighborhood. Although the project is led by Gates, a Tribune article from early June suggested that few residents from the area were consulted or invited to participate in the programming of these projects.

A few blocks northeast of the future Arts Block stands Washington Park’s Dyett High School, which will reopen in September as Dyett High School for the Arts, despite the neighborhood’s call for a science-focused school that will open up more career paths for local youth. Undeniably, arts and culture have breathed some fresh life into the neighborhoods, be it Washington Park or Greater Grand Crossing or South Shore, but their presence has not changed these neighborhoods’ economic struggles. At the very least, though, Ethical Redevelopment displays genuine care for ethics and humanism—in “ensuring that beauty remains high in the hierarchy of human rights,” as Gates put it.

As the iron door of the Arts Bank shut behind me after my visit, a woman with a baby stroller walked up to me. “What is this place? I pass by here every day and never noticed that it’s open.”

I explained the Arts Bank to her as best I could, and handed her the program I had.

“Oh, they got Frankie Knuckles here?” she said. “I love his music! I’m going to tell all my friends about this!”