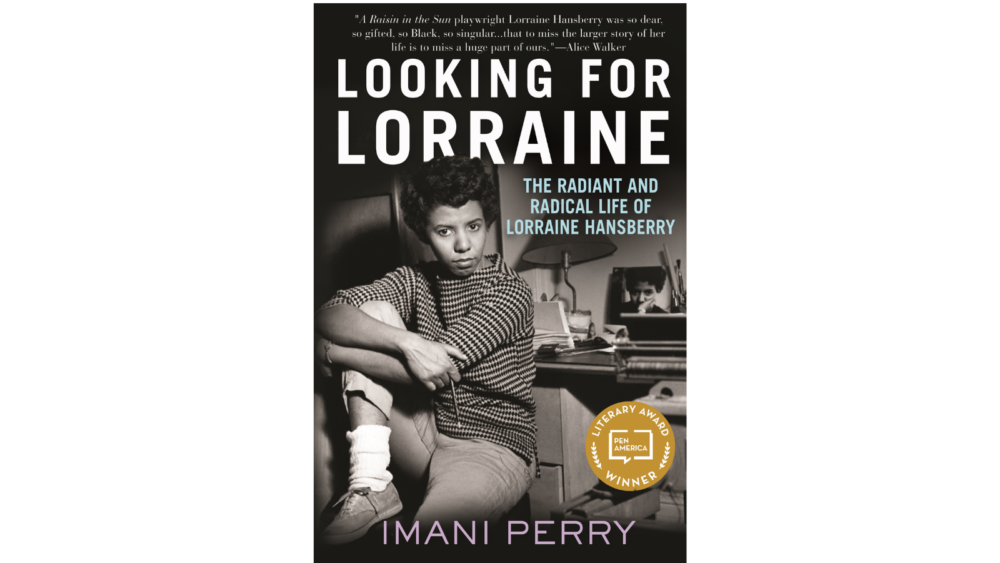

When a person leaves this world too soon, their legacy can become distorted. Often we focus on their biggest triumphs and wonder what else they could have achieved, instead of recognizing all of their successes and complexities. This is incredibly applicable to our beloved Lorraine Hansberry, a writer, artist, activist, and native Chicagoan who died at thirty-four years old. Her life was cut too short, and past biographies have primarily directed their attention toward her play A Raisin in the Sun. In her account Looking for Lorraine, professor Imani Perry argues that Hansberry’s accomplishments were actually countless—and far from ordinary.

Looking for Lorraine invites us to ponder why certain texts and aspects of Hansberry’s life are taught and remembered, while others are wrongfully excluded and left unnoticed in our public memory. With current misrepresentations of Hansberry’s life and her vast number of works, Perry begs us to investigate the full truth. In a text packed with detail, Perry fights against a previously incomplete narrative by deliberately writing about what has been overlooked.

Perry begins by shedding light on Hansberry’s foundational childhood on the South Side. With a booming Black press, Black gospel, and Black arts scene in Chicago in the 1930s and 1940s, young Hansberry was directly exposed to Chicago’s Black Renaissance. But she recognized the classist undertones of such spaces.

While occupying these exclusive spaces, Hansberry simultaneously found progressive sites in Chicago that radicalized her political ideology. For example, Hansberry discussed social realism with Joseph Elbein, a Communist Party member and University of Chicago student. Social realism was a period that emphasized the importance of artists using their work to raise consciousness, specifically for changes for the working class. These necessary conversations at a young age would later influence Hansberry’s own writing.

And although it is a site that is currently memorialized, Perry still discusses 6140 S. Rhodes Avenue to highlight Hansberry’s awareness that it was a house in the South Side that was not built with her family in mind. Due to a dispute between members of the Woodlawn Homeowners Association, one member sold the house to her father, Carl Hansberry. This decision came with several white mobs who desired for the space to remain white-only. The Hansberry’s were wrongfully evicted, and Carl Hansberry fought for his property rights and prevailed three years later.

Hansberry is young—but clearly observant of her surroundings. She was a witness to a renaissance, protests, white mobs, and legal battles. By incorporating details of Hansberry’s childhood in Chicago, Perry demonstrates that Chicago was an essential site that led to her radical politics and an inspirational location for her future creative endeavors. Even when away from Chicago, Hansberry wrote about the city. In one of her journal entries, she noted that “Chicago continues [to] fascinate, frighten, charm, and offend me. It is so much prettier than New York.” It was a city that she hoped could change for the better, but still always considered it home.

Perry could not omit Hansberry’s deliberate decision to write about Chicago in her most well-known play, A Raisin in the Sun. The play follows a Black family in the South Side who just received a $10,000 life-insurance check. Each member of the family has their own opinions on how the money should be spent, and they debate using it for education, moving to a white neighborhood, or investing in a business. Although the play is already a clear part of Hansberry’s legacy, Perry’s inclusion helps emphasize that A Raisin in the Sun is a play that deserves to be remembered.

But in order to continue painting a full story, Perry focuses on what is less known in the public memory by providing insight on Hansberry’s other projects and offering some thoughts as to why they are less remembered. Hansberry’s play Les Blancs, which premiered after her death, considers the importance of directly fighting against white supremacy. In it, Hansberry created a fictional country in Africa and there are several revolutionary moments where characters resist and cast off colonial authorities.

Hansberry also worked on an unpublished story called “The Riot” which depicts a Black community resisting white attacks and police violence. The short story was inspired by an experience she had at Englewood High School. While Hansberry was a student there, there was an attempt to increase the number of Black students, which led to white students staging a strike. Hansberry was frustrated by a weak and compliant Black middle class who did little to stop these racist strikes. Her short story is ultimately quite different and more radical than what she observed, as she creates an alternate tale where Black people resist and fight back.

Later in her career, Hansberry wrote a television miniseries called The Drinking Gourd. It was a radical screenplay which exposed the evils of capitalism that were connected to the legacy of slavery. Sadly, the screenplay was not picked up by any television station.

These are just a few examples of Hansberry’s writing, so much of which has been consigned to obscurity. A lot of her works failed to have the same level of success as A Raisin in the Sun because they were considered too radical or ahead of their time. I would argue that nothing is ever actually written before its time and, instead, a white majority was cowardly incapable of facing their demons and complicity. It makes me wonder what would have happened had more of her work been published? Who could have read it and who could have been inspired by it?

Along with remembering her works, Perry sheds light on aspects of Hansberry’s personal life that are not widely recalled. Most know of her marriage to Robert B. Nemiroff, a publisher and huge supporter of Hansberry’s work. However, Perry spends time discussing her other significant romantic relationships, including with Molly Malone Cook, Ann Grifalconi, and Dorothy Secules. Her sexuality was something she constantly grappled with. Perry incorporates a diary entry that Hansberry wrote that has a column of things that she likes and hates, and the phrase “my homosexuality” is in both columns.

Lorraine Hansberry purposefully used the words lesbian and homosexual to define herself. Although Hansberry was closeted, Perry’s acute attention to her self-identification shows us that it is not so clear-cut. Perry helps demonstrate that Lorraine Hansberry is a young Black queer woman struggling with her identity like many.

We need to remember all aspects of Hansberry–her creativity, her radicalism, her queerness, her travels, and all of her works, whether they were published or not. Perry successfully paints a clearer and fuller picture of an artist who did so much in so little time. Her text encourages us to continue to investigate, as the possibilities for further research on Hansberry are endless.

Inspired by Perry’s work, I decided to wander around the South Side and observe the sites where Hansberry stepped. 6140 S. Rhodes is about a twenty-minute walk from the DuSable Museum of African American History. Visitors are welcomed to the historic West Woodlawn and there is a sign that notes that the area is “a great migration legacy community.” At her home, there is a plaque that cites the house as a Chicago landmark and gives context on her family’s legal battles. It was this house that Carl Hansberry fought tirelessly for when others believed the area was for white residents only.

A mile away, there is a secluded park named after Lorraine Hansberry. Englewood High School, which she attended and which was about a mile and a half away from her home, changed its name to Englewood Technical Prep Academy and then closed in 2008. The campus is now home to two charter schools: Urban Prep Academy and TEAM Englewood.

I couldn’t help but wonder if there are uncharted areas that Hansberry traveled to that we are unaware of. There must be more places and people that she touched during her time in Chicago. As Imani Perry reminds us, it is urgent to find these alternative sites so that we can remember all of Lorraine Hansberry and tell her full story.

Lauren Johnson is a recent college graduate currently living in Chicago. This is her first piece for the Weekly.

My family lived in the Jackson Park Highlands on Euclid Ave. My brother graduated from Hyde Park High School in 1959. We had a big graduation party at our house and I’m certain Perry Hansberry attended. Was he related to Lorraine? The name is too much of both the Perry and Hansberry not to be? Can’t find any info. He would have been in my brother’s class? Not sure. Just remember him being very nice…

Perry was the name of Lorraine’s older brother (by 9 or 10 years). If she was born in 1930, he would have been 1920, so ’59 sounds twenty years too late for him to have graduated h.s.