Even among the countless local groups of activists to organize Black Lives Matter demonstrations in Chicago, the Arab American Action Network usually tends to supply enough people power to at least be spotted in several retweets by protesters. Rasmea Odeh, AAAN’s Associate Director, was photographed a couple weeks ago, stone-faced, holding a sign reading “STOP KILLING BLACK PEOPLE” at the emergency rally in solidarity with Baltimore’s Freddie Gray protestors.

Like the voices behind Black Lives Matter, the activism of Odeh and the AAAN is motivated by perceived abuses from those given the authority to protect, and by a marginalized community’s need for protection.

The Arab-American Action Network headquarters is on the second floor of a Dollar Shop at 63rd and Kedzie. The office’s unmarked door is the result of a 2001 fire that investigators concluded was a case of arson targeting the AAAN. The culprits were never identified, but the fire came after a series of threatening phone calls and e-mails in the wake of the attacks of September 11, 2001. Arabs in the area know to enter the markaz, or “center” in Arabic, through the black door next to the Checks Cashed sign.

Chicagoland is home to one of the largest Palestinian populations outside of Palestine, with large Palestinian communities in Marquette Park, Gage Park, Chicago Lawn, and other areas surrounding the AAAN, which in addition to serving as a meeting place for Arab Chicagoans is also a center for social services and youth activist training. In many ways, the two worlds the AAAN works in are radically different. On the one hand, it deals in brick-by-brick community building by providing after school programs and holding community events. On the other hand, the broad political landscape of the War on Terror and its impact lives of its members have meant they are constantly grappling with what it means to be Arab, especially Palestinian, in post-9/11 America. The organization and its members have often been the target of racial profiling on the part of individuals who equate Arab descent with acts of violent extremism; they have also been subject to government investigations of suspected terrorist-related activity.

The AAAN was founded in 1972 as the Arab Community Center with the hope of facilitating a unified Arab identity. At present it predominantly serves immigrants and refugees with limited access to social services. In addition to its political organizing work and educational programs for youth, the AAAN’s Family Empowerment Program provides access to Medicaid, food stamps, ESL (English as Second Language) classes, and more.

“The founders and other members of ACC knew that they didn’t exist in a vacuum and needed to focus on institutionalizing themselves and working on organizing local communities,” says Executive Director Hatem Abudayyeh, “ Helping people get jobs, find apartments, Social Security—dealing with all kinds of social services.” It was for this reason in 1995 that the ACC obtained non-profit status under the name Arab American Action Network. Abudayyeh says that these resources are essential to defending and empowering the Arab-American community against the “new, vicious draconian policies that continue today.”

“The Patriot Act is still in full force, inciting massive political repression of Arab and Muslim communities,” says Abudayyeh. “We see an increase of entrapment of Arab and Muslim men in Chicago and New York, across the country, really. We have a pretty clear political line in that regard. We see that for the U.S. government to justify these policies and an unending war on terrorism abroad, they needed to identify a local identity. Our faces—immigrants’ faces in general—are made to be the faces of the enemy abroad.”

In 2010, Abudayyeh was one of twenty-three Palestinian activists and non-Palestinian solidarity activists (their supporters have dubbed them the Antiwar 23) in Chicago and Minneapolis who were subpoenaed or whose homes were raided by the FBI due to suspicions of material support of terrorist activity. The “Antiwar 23” did not testify, and none were ever officially charged, but according to the U.S. Attorney’s Office in Chicago, the investigation will continue for up to two more years.

“All this time they have this looming over their head. Whatever they find on you, they’ll use against you,” explained AAAN youth organizer Nesreen Hassan.

Hassan believes that during the investigation into the Antiwar 23, the FBI looked into other AAAN employees, including its Associate Director, Rasmea Odeh, whose case has since become a symbol for the repression of Arab-American activists, and Palestinians in particular, across the country.

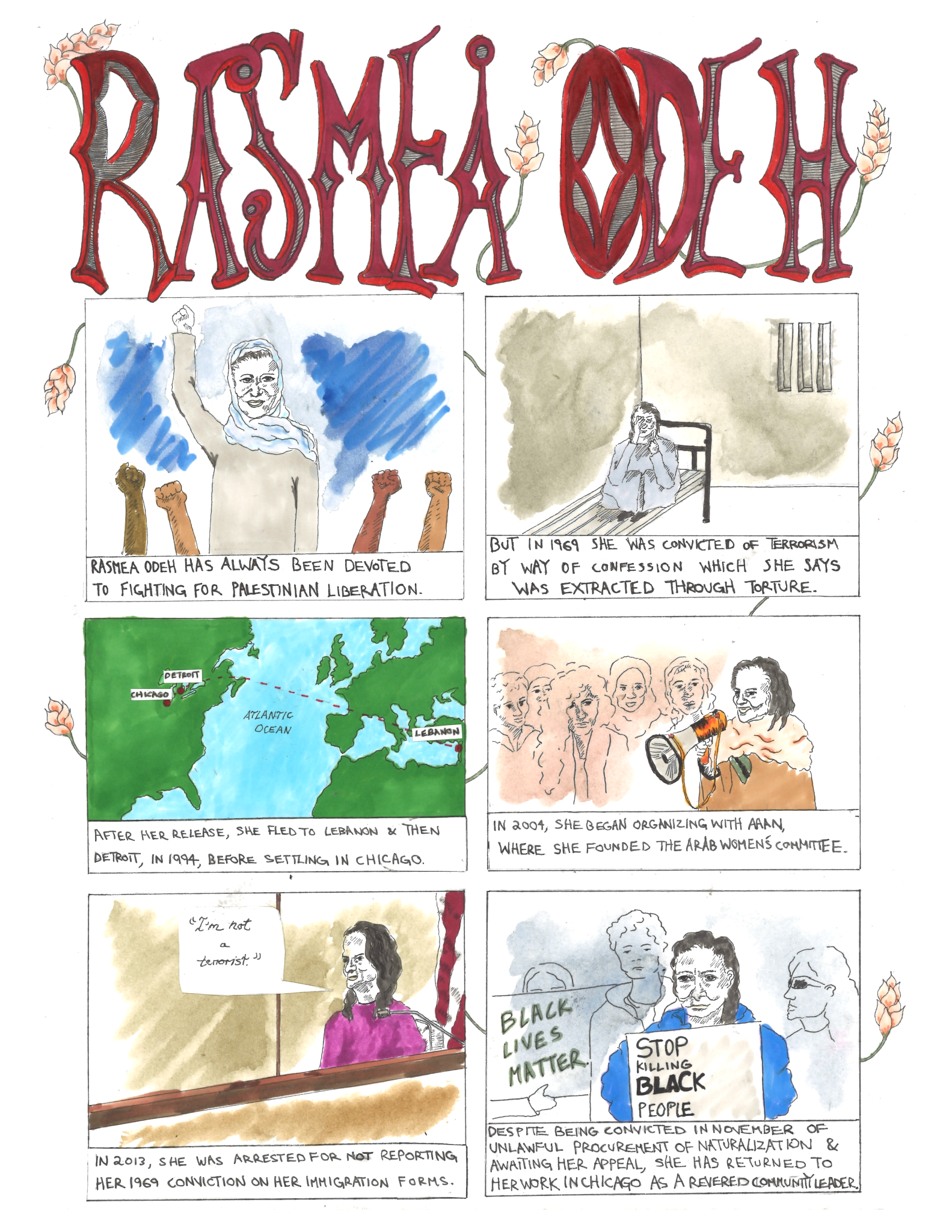

In October 2013, Odeh was charged with lying on her immigration forms during the naturalization process. Born in Palestine, the now sixty-seven year old Odeh neglected to disclose a 1969 conviction for her involvement in a fatal grocery store bombing in Jerusalem. In 1970, an Israeli military court sentenced her to life in prison, but she was released to Lebanon after ten years through a prisoner swap between Israel and the Palestinian Liberation Organization, where she continued to advocate for Palestinian liberation. She did not mention the 1969 conviction on her naturalization forms, because she claims she’d read the question as asking whether she had been convicted of a crime in the United States.

Odeh was ultimately convicted in November 2014 of Unlawful Procurement of Naturalization, and on March 12 she was stripped of her United States citizenship and sentenced to eighteen months in prison, after which she will most likely be deported to Jordan. Between 2008 and 2012, 17,000 deported Palestinian-Americans were released back onto the U.S. because it’s nearly impossible to obtain a visa from most countries for Palestinians. “Rasmea was born in Lifta, near Deir Yassin, but we’re thinking if she’s deported she’ll go to Jordan,” says Hassan. “You just never know. With Palestinians, if you get deported, you’re definitely not going back home.”

During the November 2014 trial, Judge Gershwin Drain made several pre-trial rulings that prevented Odeh and her lawyers from presenting evidence related to events relevant to the case that occurred before Odeh came to the United States, such as her claims that the confession for the bombing was extracted through torture and sexual assault, which resulted in posttraumatic stress disorder. These limitations on the evidence presented are the basis for Odeh’s appeal, set for September.

Throughout her case, Odeh has continued her work with the AAAN, and members of the AAAN have mobilized to support Odeh in return. Her initial arrest in 2013 lasted only one day because colleagues and family members were able to make her bail, and in mid-December, an anonymous donor also made her bail. She has returned to her work, writing grants, attending public Black Lives Matter demonstrations, and speaking on panels, as well as continuing to direct the AAAN’s daily work, but beyond this, she has stayed away from the press, at her lawyers’ suggestion.

“Her whole story is on public record,” says Hassan. “The embassy has it all. Coming here, of course she knows it’s all on public record. Why is it all brought up now? We definitely believe that it all goes back to Hatem.”

“We believe, and her attorneys filed a motion saying this was a case of the fruit from the forbidden tree,” she continues. “They only found this fault because they were trying to get at the Midwest 23.”

According to Hassan, the Arab and Palestinian community has become aware of the political repression by authorities like Hatem’s investigator, U.S. Assistant Attorney Barry Jonas. Jonas is best known for prosecuting the “Holy Land Five,” a group of Palestinian members of a Muslim charity called the Holy Land Foundation, who raised funds to aid Palestinians under occupation. They were initially charged in 2001 with serving as the main financial source for Hamas, a controversial resistance party in Gaza, but no conclusive evidence was found. The indictment was changed in 2004 to simply providing material aid for Hamas. After the first trial ended in a hung jury in 2009, a jury concluded that all five were guilty and assigned prison sentences ranging from fifteen to sixty five years.

Odeh has been an organizer with the AAAN since 2004 and founded the organization’s Arab Women’s Committee to create a safe space for women in the community to discuss problems at home, issues of racism, financial hardships, or life back in home countries. The Committee played an adhesive role in the AAAN, and has compiled stories of the difficulties they’ve faced as immigrant women in this country, which will soon be published as a volume in both Arabic and English. In the wake of Odeh’s conviction the members of the Committee have been central to the AAAN’s organizing to support her. “The women in the Committee love Rasmea,” Hassan says. “She serves such an important role here.”

Though she is currently facing the possibility of imprisonment and deportation Odeh continues to agitate for her own case and for the Arab-American community. Hassan is hopeful for her mentor, despite the seemingly overwhelming odds. “What they wanted Rasmea to do was sit back in the corner like a quiet lady,” she says. “I think what drove them nuts is that, if anything, she did even more organizing work.”

Despite weeks of phone calls and e-mails to those critical of Odeh and her supporters, including Jonas, few of these supporters were able to be reached, and fewer agreed to speak about the connections between Odeh’s case and other cases involving Palestinians in Chicago or the United States.

The AAAN’s main project right now is the Anti-Racial Profiling Campaign, which began shortly after a number of young members of the AAAN came to Hassan in 2012 with stories of FBI agents raiding their homes. “We knew that it was time to confront that issue—of entrapment, racial profiling, and all that,” Hassan says. Within two months the team created a survey to send out to families on the South Side and in the Southwest suburbs. More than four hundred surveys were collected, and they are currently in the process of compiling a report to distribute.

“The Antiwar 23 … Rasmea, and the Palestinians around us are familiar with the job of the government: to target those who threaten the ways the government wants to exploit people and halt transformative social justice movements,” says Abudayyeh. “Anyone in this country, whether it be the Black Panthers, the Nation of Islam, Chicano liberation movements, environmental rights movements, queer liberation movements, indigenous liberation movements…social justice movements in general are repressed. We are just part of this trend.”

Since its inception in 1972, the AAAN (then the Arab Community Center) has built connections with several local arms of the Puerto Rican independence movement, Chicano liberation groups, black liberation groups, immigration activists, among others. “It was inherently joint struggle work,” says Abudayyeh. In addition to recreational activities, cultural events, and political workshops, each semester in the after school program that Hassan leads for fourteen to eighteen year-olds, includes a power mapping activity to teach participants about local movements for Puerto Rican, black, and Chicano liberation. “Our movement is not the only movement that struggles,” Hassan says.

Correction: An earlier version of this story said that Rasmea Odeh was AAAN’s Assistant Director. She is their Associate Director.