Revise the Psalm: Work Inspired by the Writings of Gwendolyn Brooks, edited by Quraysh Ali Lansana and Sandra Jackson-Opoku will be published by Curbside Splendor in January 2017.

I moved to Chicago in 1989, leaving behind an ugly experience in broadcast journalism and the contempt for the state of Oklahoma only natives can truly appreciate. I arrived with two suitcases, a folder full of poems, and big dreams of reinventing myself as a poet in the city that fed some of my guiding lights: Malcolm X, Haki Madhubuti, and Gwendolyn Brooks.

In 1993, while working with the programming committee of Guild Literary Complex, one of the Midwest’s most significant literary centers, I was asked to help develop an idea Ms. Brooks was cooking up with Complex founder, poet Michael Warr. She wanted to hold an annual open mic poetry contest and award the winner of said contest $500 of her own monies. Not Illinois Poet Laureate cache, but a personal check from her pocketbook. This is how I met Ms. Brooks, swaddled in the democracy and generosity of her spirit.

Two years later, while driving her home after the third Gwendolyn Brooks Open Mic Award contest, I mentioned I was considering a return to academia to complete my B.A., abandoned in 1985 at the University of Oklahoma. She enthusiastically reminded me that Prof. Haki Madhubuti, her publisher and founder of Third World Press, was at Chicago State University and that I should look no other place. I was reserved about her suggestion initially, remembering my bankrupt attempt of a manuscript Third World Press rejected only a year earlier. Noting my hesitation, Ms. Brooks offered to speak with him about school, not my manuscript.

Neither Ms. Brooks nor I knew at the time that within a year we would workshop weekly in the conference room of the center created in her honor.

Madhubuti founded the Gwendolyn Brooks Center for Black Literature and Creative Writing at Chicago State University in 1990. He also initiated the Brooks Conference for Writers of African Descent in the same year. I had met Prof. Madhubuti previously, on the floor of his flagship bookstore and African-centered school. He was what many of my Black male friends wanted to be when we grew up: a builder of positive reality.

In spring 1997, Ms. Brooks sat with eleven young poets of varying levels every Tuesday evening for two and a half hours. It was joy. It was torture. It was Prof. Madhubuti who convinced Ms. Brooks to lead this one last semester long poetry workshop. Unfortunately, it was to be her final collegiate class.

Ms. Brooks in workshop was a marvel and a wonder. She was an igniter of mind riots. She dropped morsels of ideas: clippings from newspapers, poems by authors she admired, assignments in traditional forms, then sat back and watched us scramble, scrap, and heave. All the while a mischievous, wide grin on her dimpled face, rubbing her hands in delight. She loved instigating, agitating. My work benefited from her firm nudging. It also benefited from her fierce red pen.

Ms. Brooks made it very clear revision is a part of the creative process, and clearly her work is proof of that mantra. She did not believe in waste. Hers was a hand of precision, and she often spoke of laboring for months over a single word.

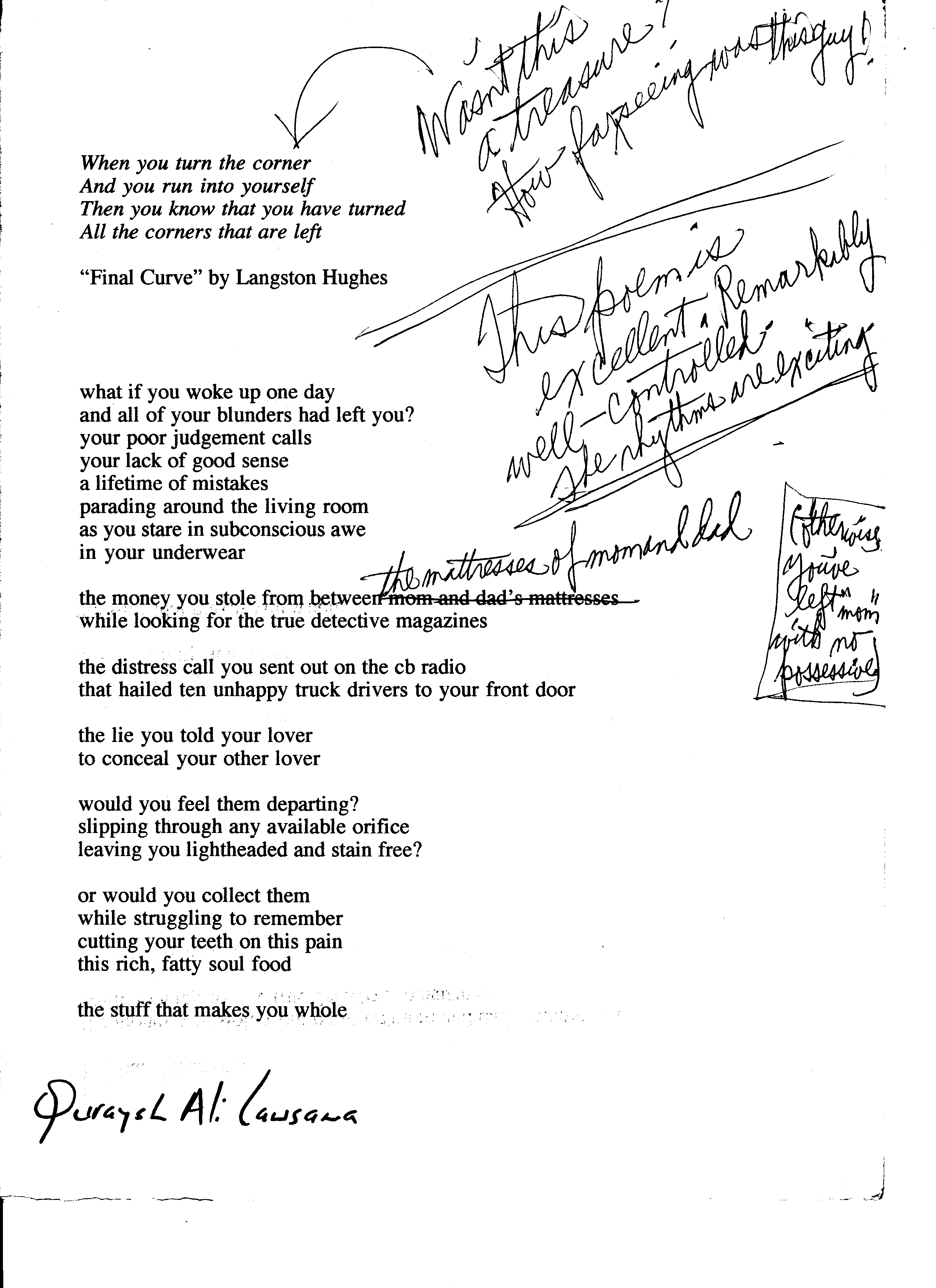

The piece that begins with the short poem by Langston Hughes (eventually titled “baggage”) was inspired by the work of my close friend and The Walmart Republic co-author Christopher Stewart. What is printed here is a later draft, very close to the way the poem appears in my first book, Southside Rain. In one of the many earlier drafts, Ms. Brooks commented on the fifth stanza by writing:

“not ‘slipping’ into? Doesn’t an ‘orifice’ have a wall?

Wouldn’t that prevent through—slipping?”

How hard-headed was I? The edits she suggests here fail to manifest in the final version.

On the same draft she wrote the following regarding the sixth stanza:

“rich, fatty soul food is also soft, so

teeth could hardly be cut upon it.”

These lines remain unchanged in the draft printed here. However, I finally caught on for the published version:

or would you collect them,

while struggling to remember

the stuff that makes us whole.

Additionally, Ms. Brooks and I tinkered with the second stanza of the draft printed here, and ultimately agreed to jettison “the mattresses of mom and dad” for “your parents’ mattresses.”

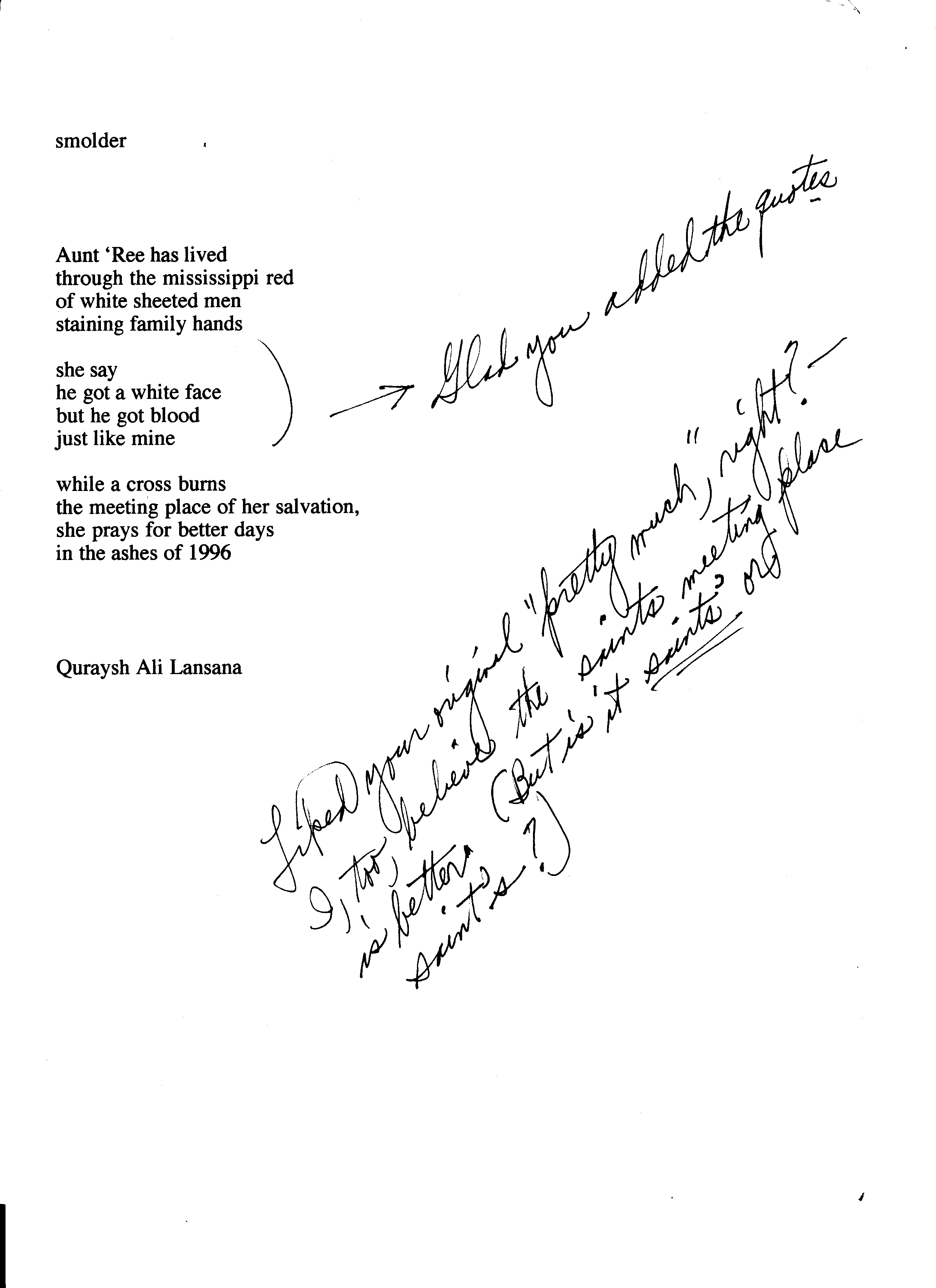

Addressing current events in verse was important to Ms. Brooks, as any student of her work is acutely aware. “smolder” was born not only of an assignment, but of the evening news hitting literally very close to home.

1995 and 1996 saw a rash of Black church bombings, in mostly Southern states, but a few in the North and Midwest as well. The First Baptist Church of Enid, Oklahoma, located three blocks south of the church in which I was raised, was leveled by a slightly disturbed gentleman who claimed he was simply “copy-catting”. Regardless of his motives, he displaced and disrupted the lives of many relatives and old family friends. My people were on edge for weeks. I penned the first drafts (the first stanza and most of the final stanza in the version printed here) in Chicago.

Perhaps a month after the First Baptist bombing I went home for a visit. While sitting in the cluttered, historic landmark that was the living room of my eccentric aunt, the late Marie Adams (we called her Aunt Ree’), I realized the depth of her struggle to forgive (one of the cornerstones of Christianity) this crazy dude who blew up any church, let alone a church in our hometown:

he got a white face

but he got blood

just like mine

Ms. Brooks immediately gravitated toward the quote. It made the poem human, personal. Something that was second nature for her.

Her comments on the bottom of the page refer to edits I implemented for the third stanza. In an earlier draft, the poem closes:

while a cross burns

the saints meeting place

she prays for better days

in the ashes of 1996

The draft printed here seems unwieldy, particularly the second line. She compared the drafts, and, after much discussion, we met in the middle for the finished product:

aunt ree has lived

through the mississippi

of sheeted heads

soiling family hands

she say

he got a white face

but he got blood

just like mine

she prays for better days

in the ashes of 1996

while a cross burns

the saints’ meeting place

At the conclusion of the semester, the class, now the Gwendolyn Brooks Writers Collective and only nine in number, initiated a tradition by taking Ms. Brooks out to dinner. She reciprocated, inviting us to a meal that next Christmas. It was at our Spring/Summer outing in 1999 that her ill health was becoming apparent. She was very frail, and, uncharacteristically for Ms. Brooks, did not have much of an appetite. We worried that she didn’t like the restaurant. She didn’t, but there was more to it than this. Prof. Madhubuti, who was always very protective of Ms. Brooks, was more tight-lipped than usual.

That August, my wife Emily, my two sons (now four) and I went to visit Ms. Brooks at her condo the day before we moved to New York City. I had been accepted to the MFA Creative Writing Program at NYU, a graduate school journey Ms. Brooks helped initiate and further. She crafted recommendation letters on my behalf and mailed them to Sharon Olds at NYU and the late Michael Harper at Brown. She was weak and clearly in pain, though gracious and playful as always. She loved my sons, and demanded to be either the first or second person phoned upon their births. She was second for both. The photo I shot of her with Emily, Nile and Onam sitting on her piano bench is bittersweet joy. It is one of the last photos of Ms. Brooks. She joined the ancestors three and a half months later.

Helping to carry her casket through Rockefeller Chapel was among the most difficult tasks I’ve experienced. I sobbed with the weight of her, of the inverted metaphor. She held me up, both prior to and after our loveship began, through marriage, births, my first teaching gig and my first book. The blizzard raging outside the chapel was also metaphor, also very Gwendolynian.

Ms. Brooks chose me, and Baba Haki groomed me to become director of the Brooks Center. This was my dream job since attending my first Black Writers Conference in the early nineties. This was the work I was built for since eighth grade, when her poetry and this new art called hip-hop changed my way of seeing. I was honored to help guide that remarkably special space for nine years, and loathe the way it ended. That is another essay.

I led workshops, taught class or held meetings in her conference room, the conference room of the Gwendolyn Brooks Center, almost every day for nine academic years. It was both an honor and a chore. But, most of all, I loved to open the door to the Center when no one was in but the two of us.