For Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., the politics and priorities of Freedom Summer never stopped. King’s arrival in 1966 from the embattled South ignited the Chicago Freedom Movement, and the conditions in northern, urban, and de facto segregated Chicago changed King and his beliefs. It was in Chicago that King intensified his call for economic justice as a goal both beyond and including racial integration.

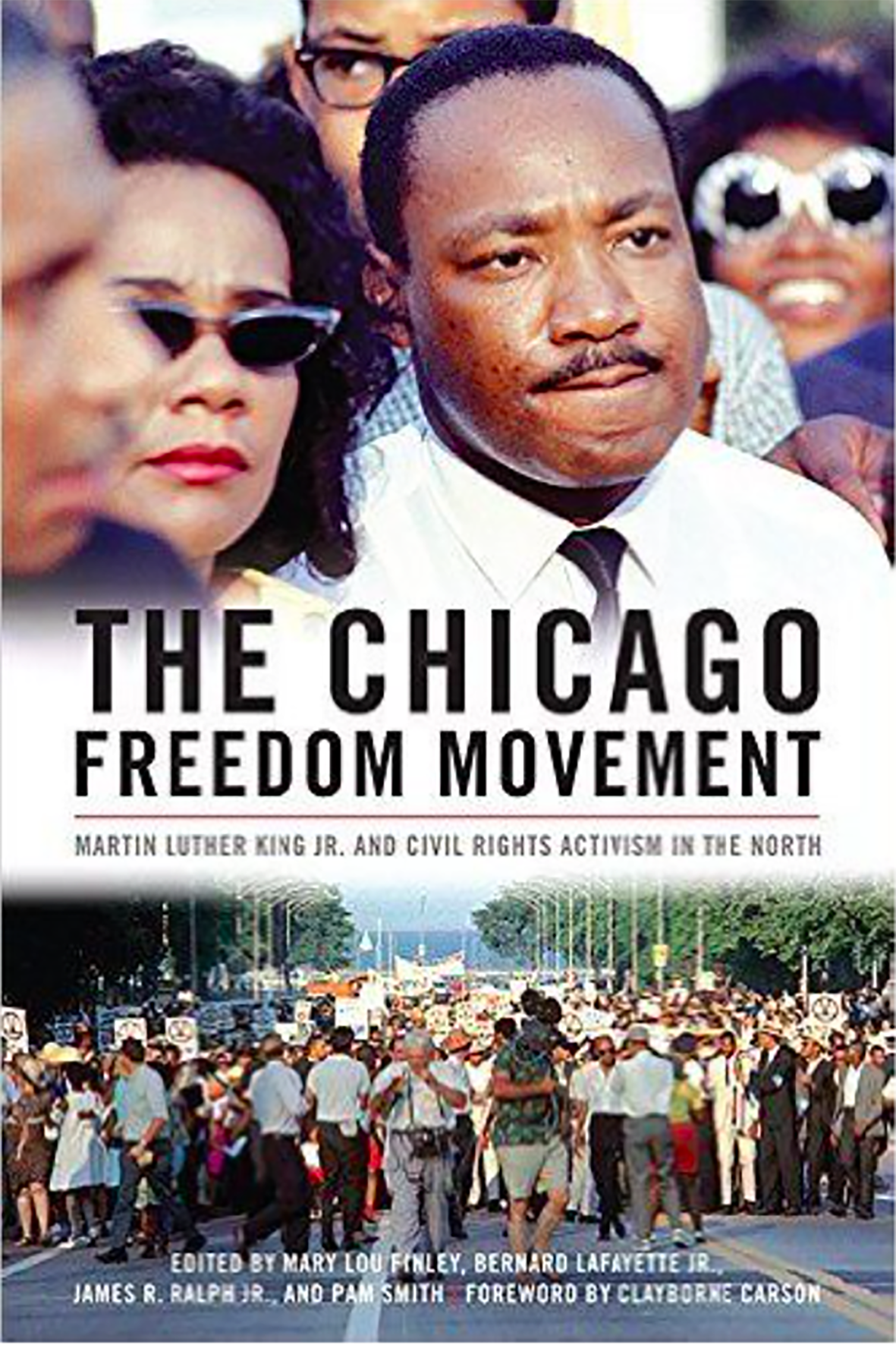

The recently released book The Chicago Freedom Movement: Martin Luther King Jr. and Civil Rights Activism in the North chronicles King’s time in Chicago in 1966. King’s fellow activists Mary Lou Finley, Bernard Lafayette, Jr., James R. Ralph, Jr., and Pam Smith edited the volume. These luminaries of the Chicago Freedom Movement document the time they spent working with King and how King’s stay in the city fits into the context of both his life and Chicago activism.

The book is really an anthology of the Chicago Freedom Movement’s different voices. Even the introduction weaves together different narratives about the movement’s impact. The bulk of this volume is made up of chapters written by people who made an impact on or were affected by King’s time in Chicago. These contributors range from movement organizers to public figures, from local mothers to political experts, and their accounts include stories of how the movement’s work can be traced directly to the present day. Their diverse perspectives lay out the background, the action, and the legacy of the Chicago Freedom Movement, highlighting the breadth of viewpoints in a movement often granted undue cohesion in historical memory.

Attention to housing rights and economic opportunity did not begin with King’s arrival. For years, Chicago groups had campaigned against housing discrimination and a lack of jobs that disproportionately affected predominantly black neighborhoods. Oftentimes these campaigns were centered on tenements. Low-income renters generally lived in very poor conditions, with homes in disrepair and water and heating services intermittent. Their landlords ignored their complaints. Whole neighborhoods were closed to African-Americans. Housing segregation was economically enforced despite being legally forbidden.

Poor tenant conditions were exacerbated by real estate offices and lenders through the practice known as “redlining.” As Mary Lou Finley describes in her chapter “The Fight for Fair Lending,” predominantly black neighborhoods were classified as unworthy of regular loans, and their residents were charged much higher rates. Additionally, real estate agents would sometimes choose “gray areas”—areas next to black neighborhoods— and transform them into redlined areas by convincing white homeowners to sell their homes at cheap prices, saying a supposedly soon-to-come influx of black homeowners would lower neighborhood property values. These same homes were then sold at much higher prices to prospective African-American homeowners, who were then given unfavorable loans. Since real estate offices offered different home options for black and white buyers of equal stature, African-Americans once again had no options except the exploitative deals.

The book explores the collaboration between existing activist efforts around housing in Chicago and King’s newly arrived staff. John McKnight, a community organizer, first heard about housing inequities in the late 1950s from West Side attorney Mark Satter. McKnight lacked the resources to fully tackle the issue at the time, but his conversations with King’s staffer James Bevel brought the issue to the fore of King’s July 10, 1966, Soldier Field rally. Fair housing and fair lending became the central focuses of the Chicago Freedom Movement, and the influence and experienced staff that accompanied King gave greater visibility to ongoing organizing efforts.

The book argues that one key success of the Chicago Freedom Movement was the attention it brought to inequities, which paved the way for continuing activism. Many organizations that began with the Chicago Freedom Movement, like Operation Breadbasket or Jesse Jackson’s Rainbow PUSH Coalition, continued to provide services to communities for decades afterward. The book’s contributors make clear that many of these organizations were directly founded during the Chicago Freedom Movement or were sustained by strong community involvement first inspired by King’s presence in Lawndale, where he and his family lived for several months in tenant housing.

The Summit Agreement between housing stakeholders at the end of the summer of 1966 as a result of King’s activism is often regarded as a failure. However, this book presents a link between King’s focus on fair housing in Chicago and the decision to honor him after his assassination with the passing of the Fair Housing Act at the national level.

In this way, lasting local change aligned with national change, a phenomenon highlighted by Rev. Jesse Jackson, Sr. in his chapter of the book. Jackson argues that while the struggle then was one for freedom, the struggle now is one for equality, since freedom of movement was achieved during King’s era. In Jackson’s view, the Fair Housing Act inspired by the Chicago Freedom Movement ended regulatory barriers to integrated communities, leaving behind the right to the same lifestyles enjoyed by whites, just not the means. Adopting the economic justice theme that was so central to King’s later beliefs, Jackson focuses the current struggle on turning the widely accepted goal of “freedom” into actual equality in the workplace, schools, and beyond.

In a panel discussion hosted by the University of Chicago’s Institute of Politics, Mary Lou Finley shared with the audience just how many links and outgrowths of the movement she had discovered while putting together this book with the other authors. When asked about maintaining motivation even though many of the movement’s goals were not accomplished for many years, she advised celebrating small victories. “See them as important, not as failures,” she said. “We didn’t end slums in eighteen months, but we did get a tenant union.”

Sherrilynn J. Bevel, James Bevel’s daughter and the author of a chapter on lead poisoning, added that continuing to work against long odds is sometimes about belief. “It’s a matter of faith that eventually justice is going to prevail. God will be with us; as well, we will be with God,” she said.

Both Bevel and Finley emphasized the role of nonviolence in the movement, saying that nonviolence provided the fundamental basis for loving the other enough to bring about change. Throughout the book and the panel, it was evident that the Civil Rights Movement created by these activists imagined more than creating opportunities for African-Americans. The stories told in this collection are about striving toward true equality in a city even as the legal barriers in Chicago were quickly being torn down.

Looking towards activism that has emerged since the Chicago Freedom Movement, Finley said that for the Black Lives Matter movement, a key step now is to identify an objective. According to Finley, “the goal of protesting is to get yourself to the negotiating table in a stronger way, not just to freely express yourself.” That being said, the most important thing for Finley was the people’s spirit: “There’s a lot of creativity and courage that should be honored,” she said.