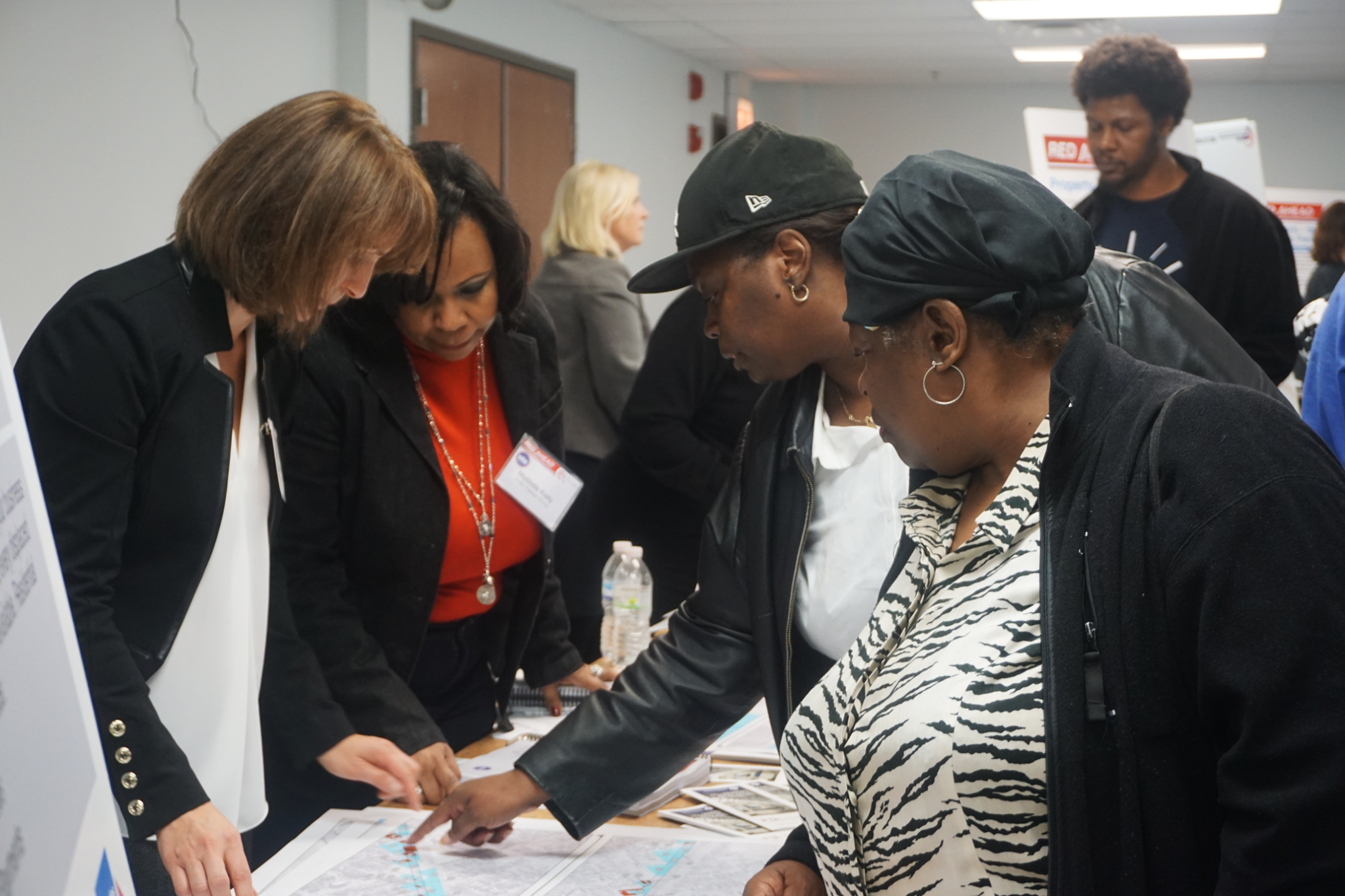

On November 1, the St. John Missionary Baptist Church on 115th Street in Roseland became the forum for discussions that could shape the future of the area for years to come—with changes potentially rippling across the entire South Side. Community members, CTA officials, and organizers came together for the only public hearing on the environmental impact statement for the Red Line extension project, the details of which were announced in late September. “The draft environmental impact statement looks closely at the potential benefits and impacts of both the east and west options,” says Jeffery Tolman, a spokesperson for the CTA, referring to two possible routes for the extended Red Line.“The public meeting was to seek out the community’s feedback.” The final route and impact statement will be unveiled in 2017, Tolman says.

The stakes were high for many people at the hearing, including Roseland residents Shari Henry and her mother Mary Thomas. The home they have lived in for years is among those that might be seized by the city to make way for the 103rd Street stop. “I was told tonight that we would receive a letter in 2017, and the decision is going to be made based on the comments received tonight,” says Henry, who says she cried at a previous meeting on the issue. “You can’t make any plans. We don’t know what’s going to happen.” Including Henry’s home, 175 homes would have to be demolished to make way for the eastern route, says Tolman, and 113 for the western route. Forty homes would be affected regardless of which option is chosen.

Only a portion of the people present were residents of Roseland, however. Many came from across the South Side, illustrating the broad impact the project could have on residents’ lives in the city. Antonio Reed, an assistant administrator in the main office of Olive-Harvey Middle College, a charter high school on the Far South Side, was among those in attendance. He says he uses a number of buses to make lengthy, daily commutes. “I live all the way in Englewood,” he says. “I come all the way to Roseland for different things like church, events I got to participate in, and the high school. I do everything in the hundreds,” he says, referring to blocks south of 99th Street.

But as it currently exists, the local transit network forces Reed to take two buses in addition to a ride on the Red Line just to get within walking distance of his various commitments. He says things are even worse for residents of the Far South Side. “We have a lot of struggles on the South Side, and when people have to work in the Loop downtown and they live out in the hundreds, it takes them a good minute to get down there.”

Complaints about transportation inequity on the Far South Side have been circling for decades, says Andrea Reed, the executive director of the Greater Roseland Chamber of Commerce (no relation to Antonio Reed). “In this part of town we talk about there being a food desert, but there is also a transportation desert,” she says. “When you’re trying to get to work and it takes you two or three hours to get there, that takes a lot of time out of the day, especially for single mothers who are trying to raise children.”

However, with the planned extension of the Red Line south from the 95th/Dan Ryan stop all the way to 130th Street, residents are hopeful their transit woes will be alleviated. Residents like Antonio Reed say the plan, which would cost $2.3 billion and affect nearly 128,000 people, would help connect residents in the area to job opportunities further north, cut down on commute times, and prevent overcrowding on buses. “I’m just glad they finally bringing it to the [Far] South Side,” Antonio says. “Ever since I was a young teenager I’ve been keeping up with the CTA—keeping up with new buses they buy, new projects they got—so I’m really looking forward to this project.” In addition to making it easier for residents to get to resources and jobs, community organizers hope the project will also help revitalize commerce and retail in the Roseland area.

“The problem is historically, transportation planning has often been to the detriment of poor African-American communities,” says Lou Turner, professor of African-American Studies at UIUC and the former research and policy director at the now-defunct Developing Communities Project (DCP), which was headed by Barack Obama in the late 1980s. “So we thought, why not use transportation planning to actually enhance African American communities?”

But Turner says that the Red Line extension project would have happened had it not been for his group’s work. He claims that it was DCP’s innovative policy thinking that got the project off the ground—“We were the origin of using TIF bonds for transportation funding in the city of Chicago, which suddenly the city and the CTA discovered,” he says, referring to tax increment financing, where local funding for transportation projects is matched by state and federal funds. “But we’d been pushing that in 2003, 2004, when nobody listened.”

Tolman says that while TIF is one of the possible funding avenues for the project, he says the final funding scheme will remain up in the air until 2017. “We’re seeking up to fifty percent of the project’s cost through federal funds, but it’s too early to say what funds we would use as far as a local match.”

Turner says that the City of Chicago had been exploring a southern Red Line extension since 1975, but that each time it concluded, more studies needed to be done before a plan could be developed. The city was in no hurry to undertake such studies, Turner says, so DCP conducted them on their own. “When we began doing studies, we found out that the city of Chicago and the planning department hadn’t done a neighborhood plan for this area in decades, so the studies that we did were the only ones that focused specifically on this area, the Far South Side.”

However, Tolman attributes this to the complexity of the Red Line extension proposal. “This project has been a long time goal for CTA and for Mayor Emanuel, and obviously it would be a transformation project for the South Side,” he says. “A project of this scope takes several years of planning, so it’s a lengthy process.”

The four studies DCP conducted were included among the twelve cited in the project’s environmental impact statement. Turner, who was present at the November 1 hearing, proudly carried the multi-chapter statement under his arm. “In order to measure the impact of the project on the area, you need to understand what the objectives and goals of the community for the area are,” he says. “And so, [in the DCP studies], we have livability objectives, environmental justice objectives, those kinds of things.”

Turner says there are plenty of other problems with the CTA’s public information process. “The organization [DCP] doesn’t exist anymore but some of the former members are still active, and we put out this letter to the CTA asking for more than one public meeting on this thing,” Turner recounts. “In fact, for all previous phases of this process, they had more than one meeting. So why is there only one on this one?”

Like nearly everyone at the hearing, Turner is looking forward to the extension project, despite his criticisms. Andrea Reed, whose constituents will be the ones affected most directly by the project, largely agrees. “The Red Line project is just one piece of the puzzle,” she says. “It certainly is going to help, but it’s not going to be the answer to everything.”

But Reed says the Far South Side will need much more than new El stations if it is going to truly thrive. “The conversation is coming up about people saying, ‘Wow, these people have been overlooked,’ but it’s intentional. Transit needs to be fair and equitable throughout the city.”

The public comment period on the project lasts until November 30, and city officials hope to begin construction by 2022. But even after the Red Line project gets off the ground, Reed says there remains much work to be done.

Katie Bart contributed reporting.

TIF bonds are an atrocious idea – especially for the south side TIFs which are relatively under-performing in comparison to the rest of the City. Increment is a fairly volatile commodity to predict, and if bonds are issued against a projected revenue stream that doesn’t materialize the City’s general obligation fund must act as a backstop. Given the overall financial condition of Chicago’s budget, it wouldn’t seem wise to add another source of stress.

If anyone needs an example of this, the City is still digging out of the negative implications from the last time they issued TIF bonds in order to pay for the Modern Schools Across Chicago program under Mayor Daley.