On October 23, 2015, the Cook County Democratic Party withdrew its endorsement of Dorothy Brown, the incumbent Clerk of the Cook County Circuit Court. Instead they endorsed 8th Ward Alderman Michelle Harris for the Democratic primary on March 15. Brown’s office, which has raised controversy for years due to rumors of inefficiency and patronage, has now come under FBI investigation. Now the heated primary race has featured allegations of job-selling and cronyism. As the turmoil within the Democratic Party deepens, it wouldn’t be surprising if Chicagoland voters are asking themselves: what exactly is going on with the Clerk’s Office? And why does it matter?

To understand the importance of the Clerk of the Cook County Circuit Court, as well as its complex relationship with the Chicago political system, one would do well to examine the case of Gwendolyn Chubb, a Chicagoland resident who filed a complaint against the Clerk’s office in 2013. Chubb had filed for divorce against her husband, Steve Shavers, alleging that she had been a victim of domestic abuse. In the ensuing court case, Shavers filed an Emergency Order of Protection, an order intended to protect victims of domestic abuse. Judge Edward A. Arce denied Shavers’s request on June 4, 2008, but in subsequent testimony, someone in the Clerk’s office had altered the records so that they said the request had been approved. The divorce case eventually became a custody battle over Chubb and Shavers’ children, and the approval of an emergency order of protection was important in the custody case. Chubb claims that the “that fraudulent document was used against me in the court”; according to a post Chubb wrote on Facebook, she did lose custody of her children, though not necessarily because of that emergency order of protection.

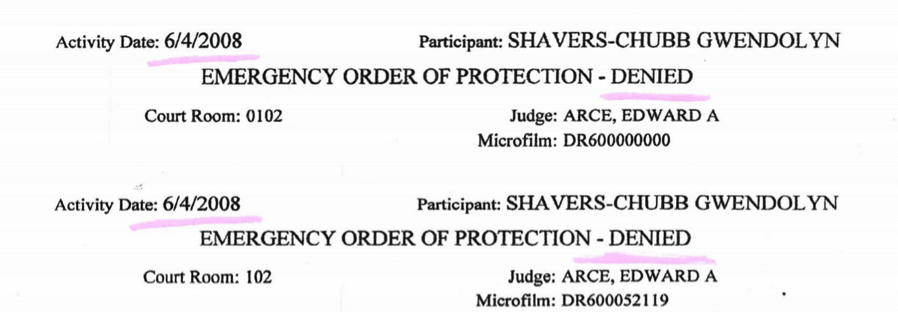

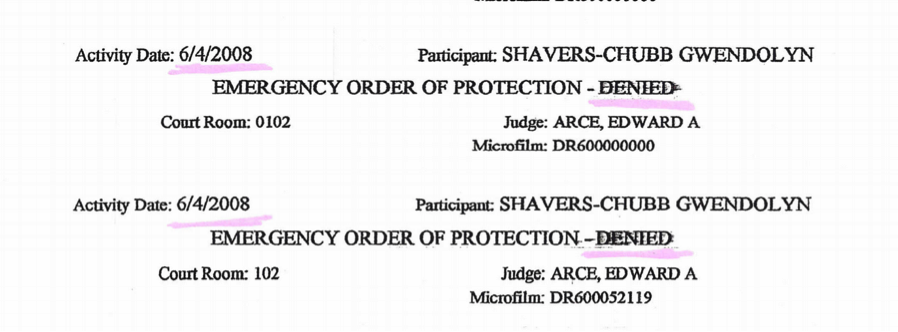

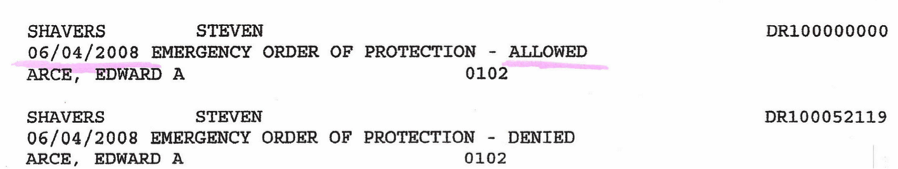

After Chubb complained to the Clerk’s Office, the record was changed back to reflect that the order had initially been denied but, frustrated by the sequence of events, Chubb filed a subsequent complaint with Mary Melchor, the Inspector General of the Office of the Clerk of the Circuit Court. She sent Melchor a number of documents: The case information summary from December 17, 2008 showed that the order of protection had been denied (1). But in the case information summary from January 13, 2011, the word “denied” had been crossed out (2). Finally, the electronic docket from November 30, 2011, after Chubb had initially complained to the Clerk’s Office, recorded that the emergency order of protection had been both allowed and denied, although only the order marking it “denied” had a valid record number, DR 100052119, instead of the invalid DR 100000000 (3).

In the subsequent months, as Chubb tells it, she spoke with Mary Melchor in person and on telephone, receiving responses such as, “I’ll get back to you,” “I thought someone had taken care of it,” and “I’ll call you back.” Chubb believes it would be trivial to check the record logs and determine who in the Clerk’s Office tampered with the file, but the case was never resolved, and Chubb found it impossible to get further updates from the Inspector General’s Office.

Chubb speculates that the dense web of political connections between Cook County officials ensured that any wrongdoing in the Clerk’s Office would be covered up. Mary Melchor’s office, according to its website, is responsible for “investigat[ing] complaints of fraud, waste, mismanagement, abuse, and misconduct by employees of the Clerk’s office.” But it was the Cook County Circuit Court Clerk Dorothy Brown herself who appointed Melchor in 2005, and campaign contribution records show that Melchor gave a total of $750 to the Dorothy Brown reelection campaign in 2002-2003. In 2014, Brown’s political action committee Friends of Dorothy Brown gave $500 to Melchor’s unsuccessful campaign for the Cook County Circuit Court Judge. (Melchor, who is running again this year, claims she did not know about the donation when it occurred.)

“If I had to take a guess,” says Chubb of her complaints against the Clerk’s office, “I can only say that there was never any intention to investigate it and they know that unless there was any media attention, even if I were to report them to a higher authority, there still wouldn’t be any consequences.” The Weekly contacted Melchor about the case, and she said she would look into it, but as of press time she had not responded.

Now (and for reasons other the Chubb incident), Brown has become a controversial figure in Chicago politics. A four-term incumbent who’s won reelection by consistently overwhelming margins, she had the reliable support of the Cook County Democratic Party for over a decade, ever since her first election to the position in 2000. That all changed this year, when the FBI began an investigation of Benton Cook III, Brown’s husband. In 2011, Cook received a North Lawndale property for free from the late Narendra Patel, who donated over $86,000 to Brown’s reelection campaigns. Cook transferred the property to Sankofa Group LLC, a firm established by Brown, and a year later, the property was sold for $100,000 to a developer. Last October the FBI seized Brown’s cellphone as part of an investigation that initially sought to examine whether the deal violated campaign financing disclosure requirements. A separate grand jury investigation has been probing hiring and promotion decisions allegedly made by Brown’s office in exchange for personal loans. The Democratic Party withdrew their support amid the FBI investigation, but Brown refused to drop out, setting up a race for the Clerk position between a long-term incumbent and Harris, the party’s chosen candidate.

Meister, an attorney who is also running for the Clerk position, argues that the Clerk’s office is so technologically outdated that it cannot perform the basic tasks of justice.

“You have on a daily basis folks in the county jail who should be released but the paperwork is wrong, the paperwork is delayed,” said Meister. “The sheriff’s department holds that person because the most recent order is to put them in here—people literally for months who are in jail when they should be out.”

Meister argues that these problems stemmed from a basic failure to move the Circuit Court records systems off paper. “The Clerk’s Office has been scanning files as they come in for approximately the last four years,” he said. “That information isn’t available—there’s a computer terminal or two at the clerk’s office where you can see the scanned documents, but that system isn’t publically available… their office still operates on their mainframe with tape backups from the mid-1990s.”

For Meister, the technological issues are inseparable from the ethical issues that lost Brown her Party’s endorsement. “It’s becoming fairly clear,” he said, “that there’s a likelihood that she has been selling jobs. That’s something that was a very poorly kept secret…I’ve heard stories of it going back a decade. You have functionally illiterate people who have been brought into the Clerk’s office who have no knowledge or background in the court system, who lack the fundamental skills to do the jobs that they need to do. And there are very good people in that office, and to the extent that the court system continues to move it along, they’re the ones that keep it going.” None of Meister’s allegations could be verified.

Brown spoke to the Weekly at her Chatham campaign office, only a ten-minute walk from opponent Michelle Harris’ ward headquarters. When asked about Meister’s criticisms, she responded dismissively.

“Poor Mr. Meister,” she said. “He doesn’t have anything else to run on but to say what we haven’t done…We are one of the largest court systems in the world with electronic filing; we were one of the first to have that in the state of Illinois. And Mr. Meister, he doesn’t even use it.”

Brown argued that she had done a great deal to modernize her office, and to make the circuit court process less byzantine to her constituents. “We are not lagging behind—we are a cut above,” said Brown. “For me to come from inheriting an office where two of the primary divisions were still handwriting in large docket books…we automated all the divisions one hundred percent.” Among a number of electronic systems—for citizens to expunge records, find surpluses owed to them from the bank after mortgage foreclosures, and prepare orders of protection—Brown remarked in particular on her establishment of an electronic filing system, which she said allowed everyday citizens to file their cases, as well as an imaging and document management system, which she claimed allowed paper files to be shared between offices and with judges on the circuit court—a sharp departure from Meister’s allegations that judges and the public were unable to access the electronic services set up by the Clerk’s office.

When asked about the withdrawal of her endorsement, Brown suggested that it was motivated largely by political concerns.

“You have people sitting there who have grand juries all of them—excuse me, some of them have been reviewed by grand juries, because anybody can call the US Attorney’s Office and make accusations against you. I imagine some of them probably had some investigations going on when they were endorsed. But mine was more political. That’s why mine became public. Because obviously it had to be political.”

At press time, Michelle Harris’s office had not responded to requests for comment.

It’s too early to say how the race will turn out. Brown was recently endorsed by a slew of mayors from the western suburbs of Chicago, as well as Congressman Danny Davis. Michelle Harris has the support of the Cook County Democratic Party, and Jacob Meister said he expects to win a large portion of the vote from voters disillusioned with Brown and skeptical of a new establishment candidate.

It is clear from the sight of an established political figure such as Dorothy Brown running against a Party-endorsed alderman that the FBI investigation has thrown Cook County politics into some disarray. But however much turmoil there may be in the Democratic Party, some things haven’t changed. When Gwendolyn Chubb heard of the FBI investigation into the Clerk’s office, she says she contacted the Inspector General’s office again about her own complaint. She was put in touch with Mary Melchor, only to hear yet again that Melchor “thought that had all been taken care of.”

(1) The initial case summary shows that the order of protection had been denied.

(2) The edited case summary, with “DENIED” crossed out.

(3) The edited docket shows both “ALLOWED” and “DENIED”.

This happens regularly in the domestic relations division of Cook County Circuit Court. It’s a feature not a bug.

It allows countless cases to flounder indefinitely in the system, lining the pockets of judges and attorneys. Still, I feel sorry for Ms. Chubb and her children.