Chicago has an urban flooding problem. The latest report on this issue, released by the Environmental Law & Policy Center and the Chicago Council on Global Affairs in March, found that climate change in the Great Lakes will result in an increase in “extreme precipitation,” heavy rainfalls that are more likely to lead to flooding. This report is only the latest in a series that have sought to quantify the problem of urban flooding in Chicago, and its disproportionate impact on the South Side. In the wake of this report’s release, the Weekly went through literature on urban flooding, and pulled out the most important numbers that describe the problem.

Across the country, the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) estimates that twenty to twenty-five percent of all economic losses from flooding occur in areas that are not designated as a floodplain—instead, these losses are the result of urban flooding. In Illinois, that number is much larger, with the Illinois Department of Natural Resources (IDNR) finding that over ninety percent of urban flooding claims in the state between 2007 and 2014 occurred outside the mapped floodplain. In Illinois, in other words, the vast majority of flooding damage doesn’t come from rivers overflowing; instead, it comes from urban landscapes and sewer systems unable to cope with rainfall, causing water to back up into streets and basements. In Cook County specifically, the Center for Neighborhood Technology (CNT) found zero correlation between whether a ZIP code is located in a FEMA-designated floodplain and the amount of flooding in that ZIP code.

The reason that matters is because flood insurance, administered through the National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP), can help cover the costs of the damage. Flood insurance, however, is only required for mortgaged properties in areas identified by FEMA as high-risk flood areas. Since FEMA’s maps don’t accurately predict where urban flooding events occur in Cook County, there’s no requirement for the vast majority of Chicagoans most at risk of urban flooding to actually carry insurance that would help them cover the costs of that event.

Some costs can also be covered through individual assistance payments from FEMA, but this funding is only available after a federal disaster declaration. This has happened occasionally for exceptionally severe flood events, but the most recent declaration in Illinois was in 2013. For everyday basement flooding, there’s often no help from the federal government.

Some homeowners are able to purchase an additional rider for their homeowners insurance, covering water damage from sewer and drain backups. The CNT’s 2014 study found 20,461 claims made to private insurers, more than five times the number made under the NFIP. This number doesn’t include all insurance companies that cover Cook County, and it doesn’t include property owners who are not covered for sewer backups or who chose not to make an insurance claim, which means the real extent of the problem is likely much greater.

Urban flooding has a serious financial cost: the IDNR study found $2.319 billion in documented damage between 2007 and 2014, while the CNT found $773 million in damage in Cook County alone between 2007 and 2011. But the cost is more than just money. In a 2014 survey of people affected by urban flooding, the CNT found that eighty-four percent of flooding victims experienced additional stress as a result of flooding, forty-four percent lost items of emotional value like family heirlooms, and thirteen percent said flooding affected the health of a family member.

Only eight percent said they lost business income, but this small percentage may understate the risk urban flooding poses to the economic health of communities. After a flooding disaster forces them to close, FEMA estimates that nearly forty percent of small businesses never reopen.

Flooding can have a similarly devastating effect on real estate. Basement Systems Inc., a basement waterproofing company, estimates that urban flooding can lower property values by anything from ten to twenty-five percent. Urban flooding doesn’t just mean wet basements: it means closed businesses, lost home value, and priceless heirlooms destroyed.

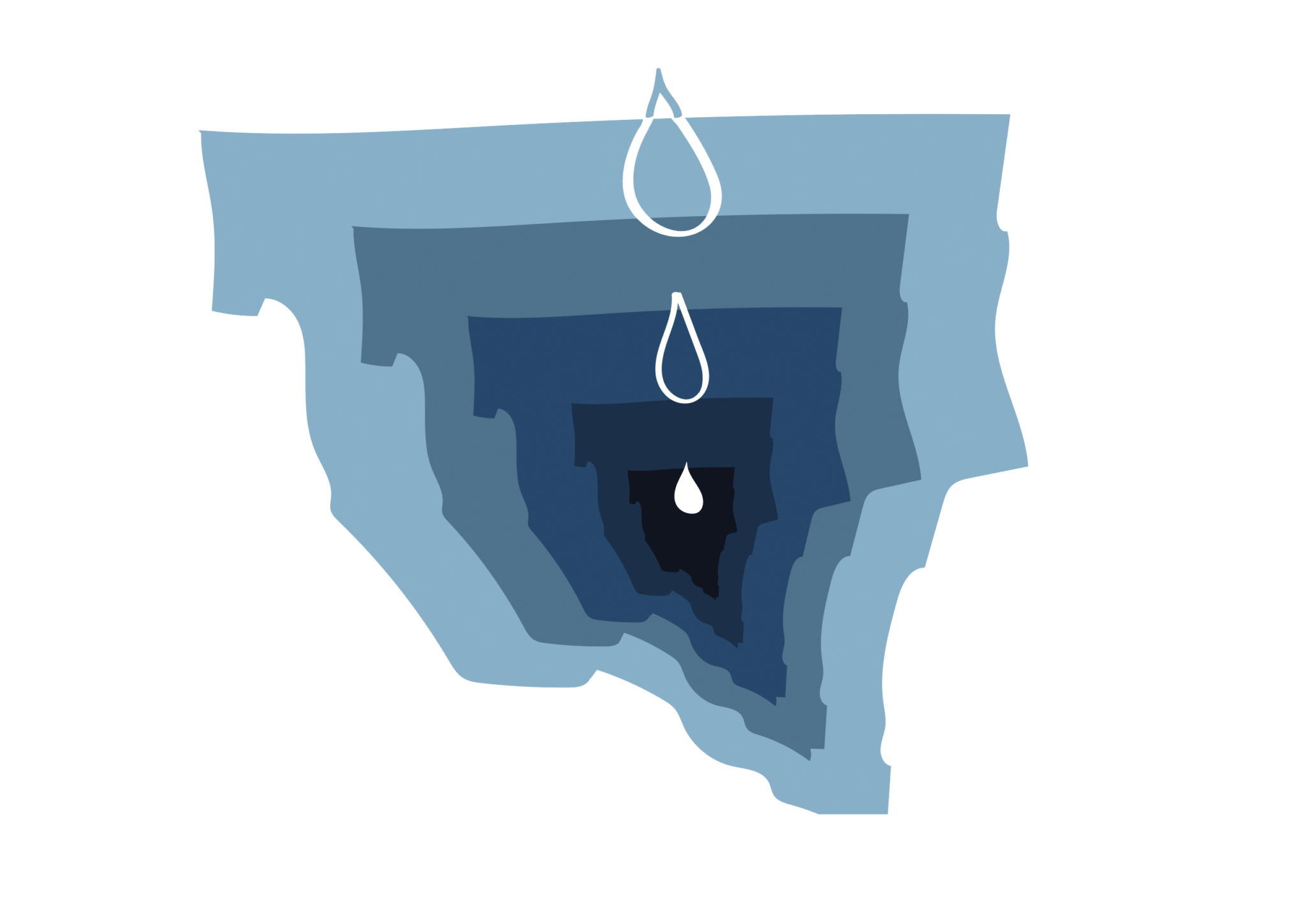

Chatham sits at the heart of Chicago’s flooding problem. The city gets more calls about flooding in Chatham and surrounding areas of the South Side than anywhere else, and the Cook County ZIP code with the most damage from urban flooding between 2007 and 2011 was 60619, which includes part of Chatham.

Before it was developed, Chatham was a low-lying area known as Hogs Swamp. While the neighborhood has changed a lot since the first houses were built, water still rolls downhill. Compounding the problem is a quirk of manmade geography: Chatham sits at the midpoint between two of the seven water reclamation plants operated by the Metropolitan Water Reclamation District (MWRD), the Calumet Water Reclamation Plant in Riverdale, and the Stickney Water Reclamation Plant in Cicero. These plants filter, clean, and release water flowing in from sinks, showers, and toilets. During heavy rains, however, stormwater is added to that existing water load, often overloading the decades-old pipes that carry water to the plants.

When an intense storm hits Chicago, rainfall in other communities fills up the sewer system first, leaving no space in the system for Chatham’s water. When that happens, water leaks out of the system in both directions: untreated sewage flows into local waterways while also backing up into basements. Because the city uses the same pipes for sewage and stormwater, there’s no way to dump stormwater in the river while reserving sewage for treatment. Instead, it all gets mixed together into sewage, and it ends up in Chatham’s basements.

Efforts to manage urban flooding began in earnest in 1975, when the MWRD began construction on the Tunnel and Reservoir Plan, also known as the Deep Tunnel. The system—still under construction—will eventually be able to contain 20.6 billion gallons of sewage. 109 miles of tunnels are already complete, and work is now underway on three reservoirs that will provide the bulk of the system’s capacity. The total cost of the project is now well over $3 billion, with more spending expected between now and the completion of the reservoirs in 2029. The MWRD’s fact sheet about the project claims that, after its completion, the Deep Tunnel will prevent $180 million in damages from flooding every year, with tunnels and reservoirs capable of holding over twenty billion gallons—enough to cover every inch of the city with five inches of water.

But the Deep Tunnel is only necessary in the first place because continued development has paved over more and more of the Chicago area’s natural wetlands. In 2014, the MWRD introduced measures to address this problem at the source, by establishing standards for the amount of stormwater that properties have to handle on site. These rules, however, are less strict than they sound. They only apply to new developments, and even then only to parcels over a certain size. Single-family homes, the dominant housing stock in Chatham, are exempt entirely. For new mega-developments like The 78, these regulations help to control urban flooding. For an older residential neighborhood like Chatham, however, the problem will persist.

And the problem will only keep getting worse. That March report from the Environmental Law & Policy Center found that climate change will result in an increase in “extreme precipitation.” When temperatures increase, water evaporates more quickly, and a warmer atmosphere can hold more water vapor. The overall impact on precipitation is mixed, but more of the rain that does fall will fall in heavy bursts, often exceeding six inches. These intense storms saturate the ground, leaving the water with nowhere to go but into the sewer system. In Chatham, that means a lot more water ending up in basements.

Undisturbed, nature does a great job of handling rainfall: some of it is absorbed into the ground to nourish plants, some is absorbed deeper into the ground to form aquifers, and some runs downhill to form rivers and lakes. One of the consequences of urban development, in Chicago as in every other city, is the loss of this natural drainage system. Green space is replaced with pavement and buildings, and there are fewer trees to absorb water, fewer places where water can enter the ground, and fewer paths to rivers and lakes.

One way to control urban flooding—one that’s a lot cheaper than building new reservoirs—is turning pavement back into forests. Natural areas, especially wetlands, offer a place to hold stormwater while the rest of it works its way through the sewer system. As the CNT notes in their report on flooding in Chatham, the neighborhood’s place at the end of the sewer system is a blessing as well as a curse: while it means there’s often no place for Chatham’s water to go, it also means water from other communities never ends up in Chatham. Chatham can control its own destiny, and can solve its basement flooding problem by creating a place for water to go.

Individual homeowners have already done this by installing “rain gardens,” planted areas that absorb rainwater. Rather than going into the sewer system, the water soaks into the ground and is eventually used by plants. The CNT’s survey of residents found that rain gardens are one of the most inexpensive ways to help prevent flooding, estimating the cost of a rain garden at around a quarter of the cost of waterproofing a basement.

Well-designed natural areas can further help control stormwater. Brittany Janney and Michelle Giles, students at Roosevelt University, studied this question over the summer with the Field Museum’s Urban Ecology Field Lab. Their research, which they presented at the 2019 Wild Things Conference in Rosemont, explored water infiltration rates in different parts of the Burnham Wildlife Corridor along the south lakefront. They compared restored natural areas to turf areas, hypothesizing that natural areas, full of native plants, would be able to absorb water more quickly. Their results confirmed their hypothesis: natural areas are significantly better at managing stormwater than parks, and native plantings in parks and along boulevards can allow these places to contribute to stormwater control.

But how much is needed is an open question. The Calumet Stormwater Collaborative, a collaborative effort organized by the Metropolitan Planning Council, recently announced their plan to develop an estimate of the current urban flooding problem in the Calumet region, which includes Chatham, as well as estimates of both green infrastructure and stormwater management capacity. This data will be used to develop specific solutions for different communities, responding to their different needs and capacities.

Sam Joyce is a contributing editor at the Weekly and the director of fact-checking. He last wrote for the Weekly about a tour of Jackson Park led by the Jackson Park Advisory Council.

All I can say is WOW!!!

Thank you for explaining and exposing this important issue!!! Next project- rain garden!!!