At the Chicago Justice Gallery, over one hundred names of Black Americans who have died from police brutality since the 1980s are listed on a wall as part of an ongoing photo exhibition, Echoes of Ferguson, at the University of Illinois, Chicago.

Last Thursday, that wall was projected with pictures of Breonna Taylor, a twenty-six-year-old Black woman who was killed in her sleep after Louisville Metro police executed a no-knock warrant on her apartment.

“This is the day Breonna Taylor became an ancestor,” said Lola Ayisha Ogbara, program director and curator of the exhibit. “Our ancestors are with us, they’re looking over us and they are here every step we take.”

Taylor’s death sparked a summer of protests and increased recognition of #SayHerName, a national movement that recognizes the often overlooked police violence that is perpetuated onto women, and specifically Black women.

Since August, the Echoes of Ferguson exhibit has explored and commemorated the ten year anniversary of Michael Brown’s death and the racial justice protests that followed. Brown was eighteen years old when he was shot and killed by police after an altercation in Ferguson, Missouri.

On the five-year anniversary of Taylor’s death and in honor of Women’s History Month, the exhibit hosted a sound healing event called Echoes of Healing.

“Sound or music has always been a playlist to insurgency,” said Ogbara about the choice of creating an event related to sound. She listed Black artists such as N.W.A, Queen Latifah and Billie Holiday, who have all used music to talk about oppression.

To explore the emotions surrounding Taylor’s death, the event fused electronic music, audio of social justice activists speaking about Ferguson, and musical performances from local artist and flute player Barédu Ahmed, whose artist name is BSA Gold, and local Black musical chamber D-Composed.

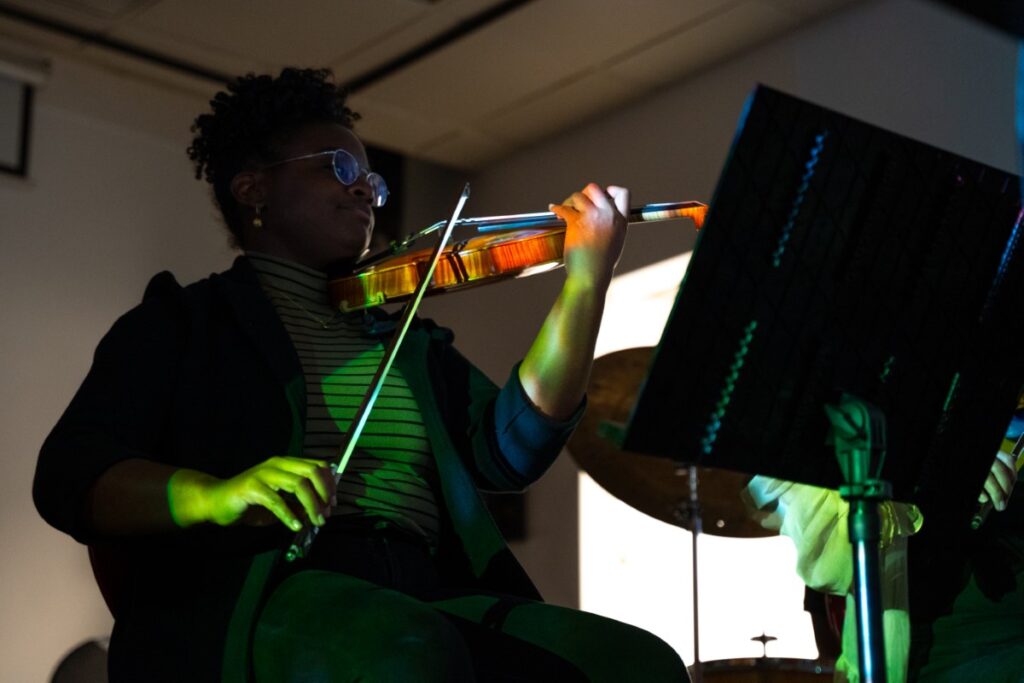

The all Black musical chamber, made of eight classical musicians, “exclusively play the works of Black composers,” said Khelsey Zarraga, a violinist of D-Composed.

With four members at the event—two violinists, one cellist and one violist—the musicians, a drummer, and BSA Gold, who played keyboard, flute and synthesizer along with slight harmonizing vocals, gave a journey that aimed to reflect the emotions of the racial justice work and community healing.

According to a 2007 article in the International Journal of Healing and Caring, “sound healing is the therapeutic application of sound frequencies to the body/mind of people with the intention of bringing them into a state of harmony and health.”

This can be achieved in multiple ways like singing, using sound bowls to release specific frequencies, or listening to instruments.

“Sound and music is so important to the Black community,” Zarraga said. “It’s the way that we connect with each other, with ourselves. That’s not just exclusive to the Black community, but the way that happens for Black folks is in a way that hits on our identity in a very important and kind of focused way. And so because of that, there’s no limit to the power of healing.”

Gold, who composed the performance, said that over the years she has increasingly understood how music connects and impacts people. “It’s something you feel, it’s not something you can see, and that’s a really mysterious, mystical, incredible, cool thing to be a part of,” she said.

In a low-lit room that hosted a crowd of nearly forty people, the event began with a three-minute breath exercise to help “reset us as a site of respite, as a site of reflection, but also a side of decompression,” Ogbara said.

Afterwards, the musical performance opened with audio from Brittany Ferrell, a Ferguson activist who spoke about their reflections.

“My time on the ground in Ferguson, my very early days is when I came into my identity as a Black feminist. It’s when I came into my identity as an anti capitalist. It’s when I really began to develop a queer politics. It is when I began to develop a language.”

As the audio played, the strings and drums of D-Composed began to creep into the background to create a rising tempo. But as the clip came to an end, the room was immediately filled with the high-pitched strikes of a violin and deep undertone of a cello.

“We broke the performance up into four acts to tell a story,” Gold said. “The first act was about the boiling tension that was happening beneath the surface in regards to police brutality and how it exploded into what we know as the Ferguson uprising.”

Gold, who uses electronic music along with playing the flute and piano, said that using electronic sounds “allows for limitless possibilities.”

“I started with a drone sound that was coming from my electronics and then the strings layered on top of that. Then we had the drums to create this overall soundscape that you understood to be a sense of rage or a strong emotion,” Gold said about the opening act.

As the act continued, the sound of tornado sirens from Gold’s synthesizer engulfed the room as the drums of D-Composed increased in momentum.

Gold said that marrying her typical percussion sounds with the strings of D-Composed presented a new opportunity of how the performance could sound.

“The audio was going to tie us together,” Gold said about the voice recordings of Ferguson activists. “But the way that we wanted to use the audio was that we would layer it over the music, or under the music, or maybe the music would have a moment by itself.”

As the performance continued, tears, nods, and smiles floated over audience faces as the three following acts explored grief and sadness, community spirit, and release.

The voices of Ferguson activists weaved throughout the performance to provide narration and reflection.

As the night ended with a song written for Taylor by Gold, water sounds flowed throughout the speakers.

“We have a bunch of pictures of Breonna Taylor smiling, and if there’s any clue as to what kind of person she might be, it’s her smile. And so I decided to make a song thinking of Breonna’s smile,” Gold said. “I still wanted to honor it with the sadness, a more somber tone, but also mixed in with just a celebration of her.”

After the performance ended, a microphone was passed around the room to allow audience members to discuss reflections of the performance.

“I definitely felt a shift when I sat down, just even telepathically I could just feel it,” said one. “It felt very sacred, it felt like something I’m going to take with me for a long time.”

Another spoke about the range of emotions they felt throughout.

“When I think of sound healing, I’m like, ‘Oh, it’s gonna be sweet. It’s gonna be soft.’ And then it started out not either of those things,” they said. “I think the second song with a lot of violin felt like a lot of anger to me and was very activating in my body. But then being able to have that followed by water was really moving.”

Messejah Washington, a student at UIC, said he could feel some of the sound healing properties after the event.

“It was a beautiful event,” he said. “I feel relaxed but at certain points, especially when the music began it was very intense and you could tell, just from the melody, that there was a statement to be made.”

The Echoes of Ferguson exhibit is open Wednesday-Friday, 12-4pm, and additional appointments can be scheduled on Tuesdays. It runs through May 25.

Jewél Jackson is an investigative, multimedia storyteller who reports on society, culture and youth.