For residents of Chicago’s Southeast Side, new developments tend to come with asterisks attached.

A new small business selling sports uniforms and equipment—that doesn’t have the customer base to support its higher prices. An apparently cutting edge coal-to-gas plant that was proposed in 2011—that couldn’t pass emissions tests and verify its clean status. Or a new gas station—that would have to compete with ones with lower taxes and prices just blocks away across the Indiana border.

More recently, Reserve Management Group (RMG) closed its General Iron facility in Lincoln Park and attempted to build a metal recycling plant on the Southeast Side despite a long history of environmentally damaging impacts. After a pressure campaign led by local residents to stop the proposal, which featured a month-long hunger strike, the Chicago Department of Public Health denied the permit in February.

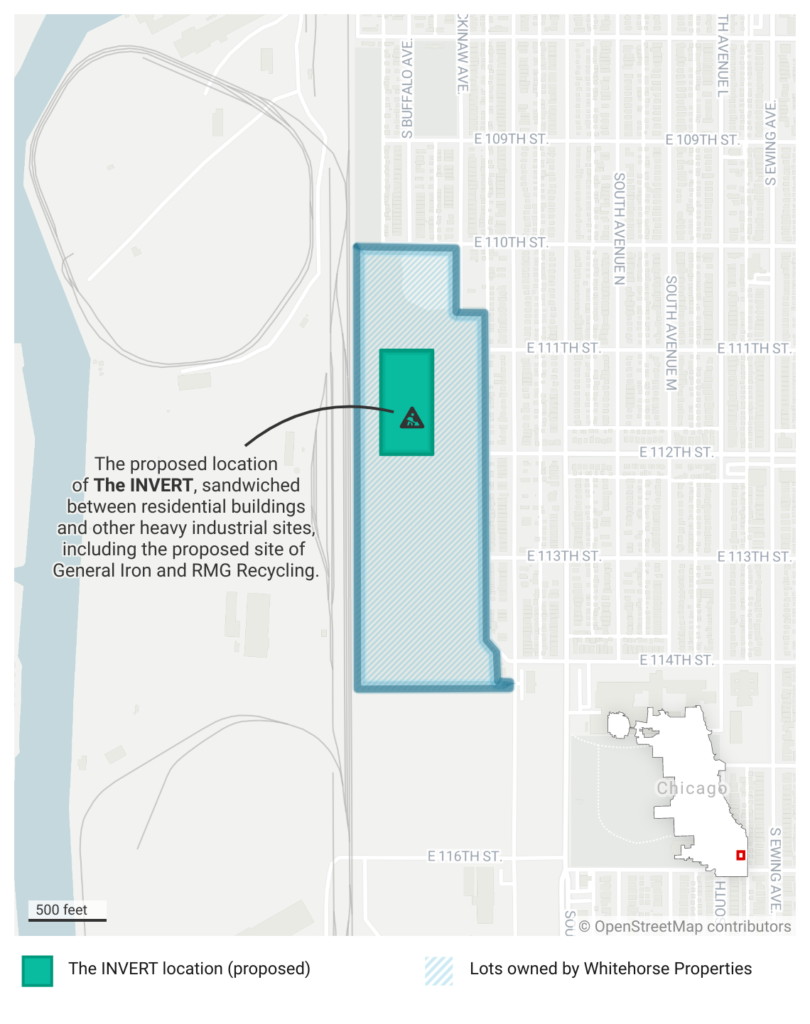

But as organizers of the campaign celebrate their victory, East Side residents are already contending with a new development proposal. Ozinga Ventures, the venture capital arm of Chicago’s concrete giant, is financing the development The INVERT, which wants to build a sub-surface shipping and logistics facility at 11118 S. Buffalo Avenue in East Side, immediately north of General Iron’s proposed lot. Among its efforts to win over the community, The INVERT claims it will bring green jobs and is soliciting local input before putting forth a proposal to City Council.

Yet some residents are skeptical—not only of whether The INVERT development will be good for their community, but if outside developers can be trusted given the region’s patterns of disinvestment and environmental injustice.

For Olga Bautista, an East Side resident and Executive Director of the Southeast Environmental Task Force, the focus of organizations and community members shouldn’t shift from one private company to the next—it should remain squarely on the City of Chicago and its regulatory policies for industrial corridors.

“My problems are not with these companies. My problem is with the city, because they have such a low bar when it comes to public health in industrial areas, and because we live in a world-class city, you would think that protecting public health, and policies that are rooted in equity, would be easy to do,” she said. “Everything that our mayors and our elected officials talk about, like equity and all these flashy words, [like] sustainability, all these things. But I’m more interested in the how. How will you do that, exactly?”

But the influence of the former plants is far from gone, and has lingered in the form of polluted soil, drifting particulate matter, and environmental issues. Respiratory issues like asthma and COPD are common, and the soil of parkland and front lawns typically yield higher than acceptable levels of cadmium, manganese, and nickel.

Prior to arriving at her post at the Southeast Environmental Task Force, Bautista worked with the Alliance for the Great Lakes, pulling together the Calumet Connect Databook—a compendium of research and development guides for planners and residents about the industrialized nature of the region. The research team, including Bautista, ran its own testing of temperature and air quality and stacked it against that of the city and other peer-reviewed journals, painting a portrait of the neighborhoods within the Southeast Side and what needs to be done moving forward.

“What we discovered was that our neighborhood has the highest incidences of COPD, of heart disease. We’re a community that is medically underserved,” she said, adding that “the burden of proof is on the community members,” and that they’ve “stepped up to the challenge” by conducting their own research and data collection and training residents in citizen science.

Not every industrial corridor in Chicago shares this fate. Lincoln Park, on the city’s North Side, had one of the most dense concentrations of industrial and manufacturing properties along the North Branch of the Chicago River for a large part of the city’s history. But that neighborhood, which is whiter and more affluent, has flourished economically after years of remediation and redevelopment.

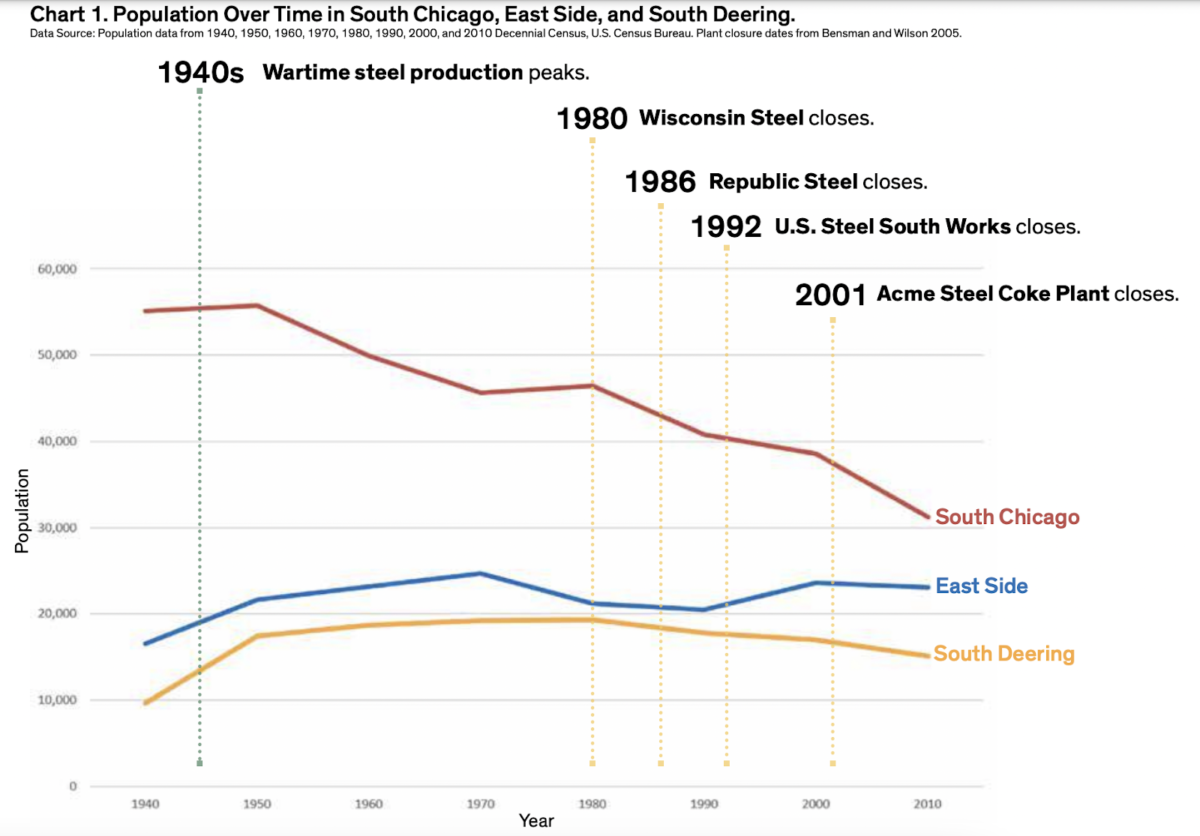

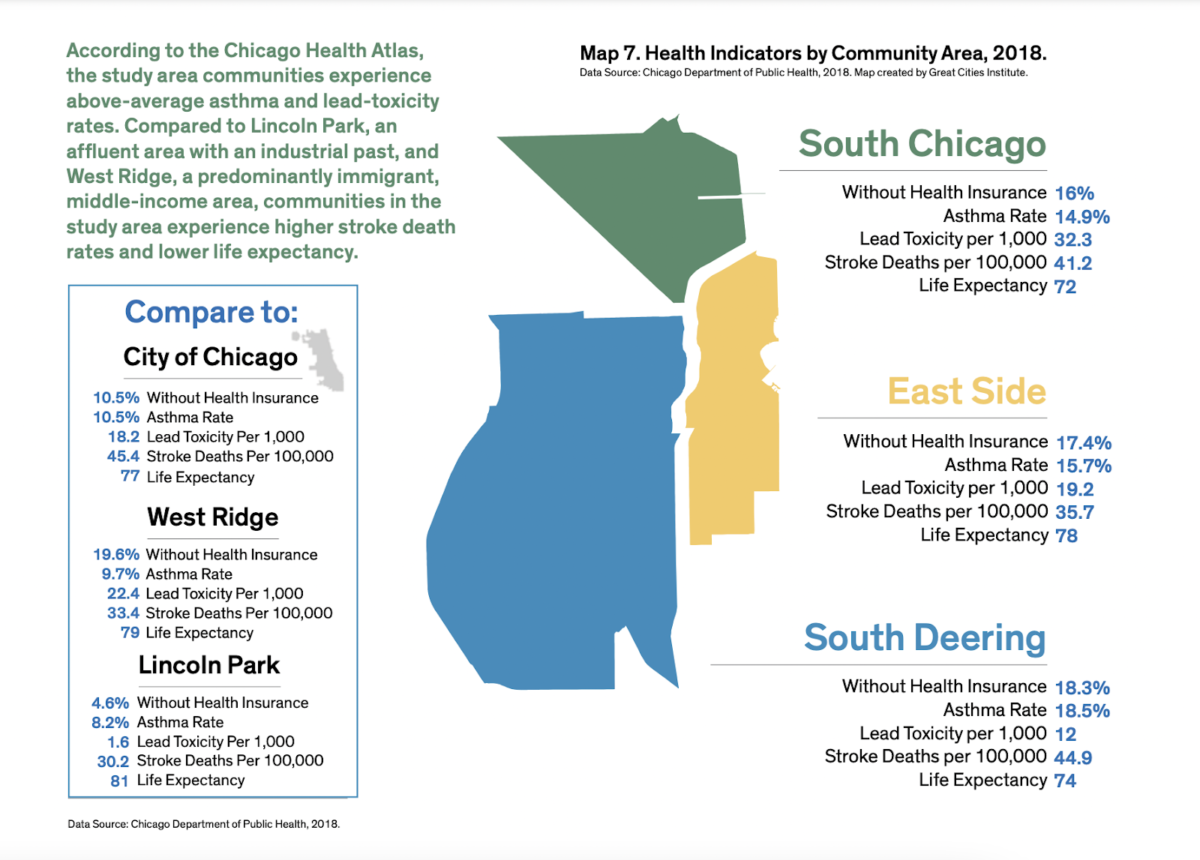

Lincoln Park residents are also healthier. In 2019, researchers with the University of Illinois at Chicago’s Great Cities Institute compared the socioeconomic and environmental impacts of these regions’ industrial legacies. In their report, the Calumet River Cities Planning Framework, they found that in addition to residents of the Southeast Side region having an average life expectancy of three years below the citywide average of seventy-seven, there were stark differences between the formerly industrialized and affluent Lincoln Park and their study region, which spanned East Side, South Chicago, and South Deering. Those differences included drastically different rates of health insurance coverage, in addition to higher concentrations of lead toxicity and asthma in the latter region.

So not only are residents of the Southeast Side, who are largely low income and people of color, forced to learn about, vet, and in some cases combat the moves of multimillion-dollar polluters—they do so while navigating chronic illness and an impacted quality of life caused by industry.

Over the years, industrial companies based in Lincoln Park have moved out, some to the Southeast Side. In 2014, Finkl Steel moved from Lincoln Park’s Clybourn industrial corridor to a new spot in Burnside, at 93rd and Kenwood. RMG tried, unsuccessfully, to move its General Iron facility from Lincoln Park to the East Side. And while Ozinga hasn’t announced plans to move the Lincoln Park location of its concrete business, it is actively looking to develop in the Southeast Side, by buying up land and investing in The INVERT.

The proposed INVERT development would be located on the site directly north of the General Iron/RMG site and directly south of the East Side Little League field. The site, which is largely grass and shrub, is a brownfield site, an under-utilized, industrialized lot with potential or actual contamination from hazardous materials. The INVERT’s team was drawn to the property because of its potential for reuse, according to public relations head Jim Sibley, and inspired by past projects like SubTropolis, a fifty-five million square foot abandoned mine-turned-storage site in Kansas City that is now host to one of the country’s largest shipping and logistics operations.

In order to build on brownfield sites, developers typically have to remediate them—clean them of pollution to a passable level determined by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), so the construction process doesn’t further spread contaminants or create a hazardous environment for residents and builders alike.

According to the INVERT, the land they want to build on is contaminated, but remediation isn’t necessary because the contaminants are “buried in gravel, slag and other crushed material,” up to thirty feet below ground. The developers’ construction approach—vertical shafts, to minimize the amount of surface-level disturbance—is “located away from the hotspots” that are monitored by the EPA, with the system for trucks to course in and out being located where contaminants aren’t, on the east side of the lot.

11118 S. Buffalo Avenue, the proposed location for INVERT, and its surrounding lots are currently listed as being owned by Whitehorse Properties, a company headed by Alan and Simon Beemsterboer, of Beemsterboer Slag Corporation, according to the Secretary of State’s office. In 2014, the company fled Chicago amid legal challenges and pressure from then-mayor Rahm Emanuel to cease storing and importing petroleum coke, or petcoke, on its property at 106th Street. Petcoke has been directly tied to worsening respiratory issues, and open storage of it—when the substance is stored openly in massive piles, often uncovered—is routinely fought by environmentalists and public health experts. The company has since removed its store of petcoke.

Another company, KCBX Terminals, was also wrapped up in the discussions about proper petcoke monitoring. Piles of petcoke, while monitored, still sit directly next to The INVERT’s proposed location and the houses beyond.

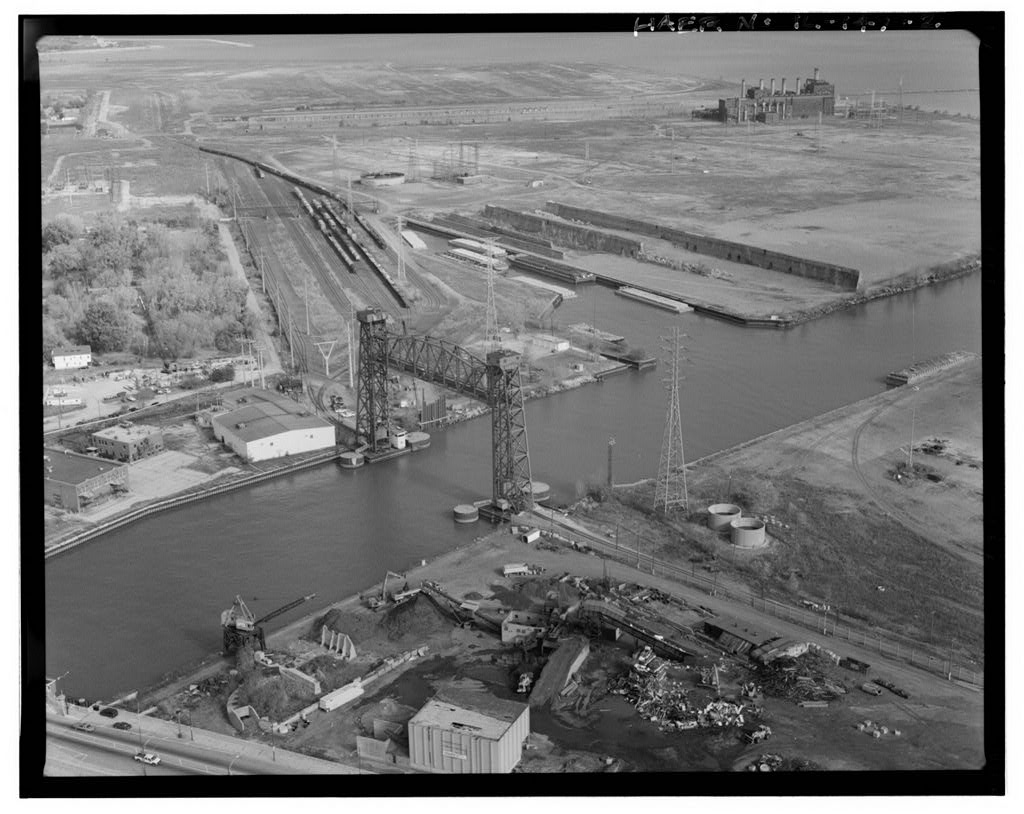

The East Side’s fraught connection with industrial developments—and their effects on locals—means residents are careful when approaching potential developments. But the region’s history as an industrial and manufacturing powerhouse, and the roots of many families in that history, is hard to ignore as companies eye abandoned sites for redevelopment.

“When I was a kid, coming up, that was kind of where we saw ourselves. We saw ourselves as the parents or other family members working in the mills, you know, one day I’m going to go up, and I’ll probably work in there,” lifelong resident Roberto Eckes said. “But once the stuff closed down, the economy, if you will, was devastated.”

“A lot of people and family members that I knew were hanging around. Always hanging around because they thought the jobs were going to come back.”

Around 2010, a redevelopment proposal was made to turn the shuttered US Steel South Works site in South Chicago into housing with a private-public partnership including almost 14,000 single-family units and a possible lakeshore events venue. Known as the McCaffery Development, Eckes said the response was incredibly mixed. Sure, housing was good, he remembers people saying at community meetings, but weren’t jobs better? And for people who already have homes here, why would they need a different one?

“People in our community need jobs, especially. Like, people are selling drugs or selling their bodies, you know, because they don’t have these opportunities. And this is what you’re not offering us,” Eckes said.

Eckes, who is a member of the grassroots community organization R.I.S.E. South East Chicago, partnered with other organizations to try to put a stop to the development itself over fears of gentrification and a lack of investment in the community. The development was axed in 2016 after U.S. Steel and McCaffery “split,” according to a DNAinfo article.

This idea—of investing in the future for people to potentially relocate to a community, instead of pouring resources into the present and the people who already live there—is something that former Southeast Environmental Task Force executive director Peggy Salazar is all too familiar with. As someone who has lived in the South Chicago and East Side communities for decades, who grew up across the street from steel mills and whose husband worked in them, Salazar’s commitment to seeing her neighborhood succeed runs deep.

“One of the difficult things for communities like ours is that for decades, we are ignored and there’s no investment in them. Then when they do come to invest, they do things with the hopes that—and we know this to be a fact—the current residents who are here will not be able to stay and afford to live here once they do revitalize the area,” Salazar said. “So we know that’s the pattern. It’s a given. It’s a pattern…Where’s the balance? How do we balance that?”

The pattern of transitioning formerly industrialized areas into ones that can generate revenue for developers is a pattern that exists far outside of just Chicago. And for a city with a prominent manufacturing history, Chicago—and especially the North Side—hides it well, according to urban planner Nicholas Zettel. While conducting research at the University of Illinois Chicago, Zettel closely looked at how cities develop and redevelop our industrial zoning and corridors. According to him, emerging manufacturing corridors aren’t as visible within central business districts and more affluent parts of cityscapes as they used to be, especially as developers pivot to sleek, green builds.

“Manufacturing doesn’t mean that something with smokestacks is going to come into your neighborhood all the time anymore, so the toughest thing in a high land value market is trying to convince people that you could repurpose land for what the next thirty or forty or even fifty years look like for manufacturing resurgence,” said Zettel. “And this is going to be cleaner industries. It’s going to be smaller; they might change faster.”

According to Zettel, when it comes to redeveloping industrial land and imagining a future for manufacturing, developers “just don’t have a concept of how to use that type of zoning or how to focus on that type of land use, because in urban development the first, most important thing everyone looks at is to make sure you get ‘highest and best use’ out of every single parcel.”

“That to me is like the biggest challenge right now, because a lot of developers and people who are in real estate…they just won’t hear it. They do that traditional 1980s-style development still, where as soon as manufacturing becomes obsolete, you shift over to high-end residential, and that’s how you make your money on your land,” he adds.

It’s this kind of approach that leads to a shut-down steel mill to be redeveloped into a multimillion-dollar housing, entertainment, and retail project—and that’s not McCaffery. That’s what has happened to the abandoned site of Finkl Steel on the Chicago River in the city’s North Branch industrial corridor, now rebranded and redeveloped into Lincoln Yards, a sprawling riverfront megadevelopment slated to break ground later this year after years of tense dialogue between neighbors and business owners in the area.

According to The INVERT, in the first stage of its process, the developers project they will create 300 construction jobs, with “the potential to add over 250 permanent jobs” per year in addition to construction-related positions until the development is completed.

“This could be the biggest job-creating project on the Far South Side in decades,” said Alberto Rincon, the head of The INVERT’s community impact efforts. Previously, Rincon was an environmental activist and director of the neighborhood’s Southeast Side Coalition to Ban Petcoke.

For Eckes, the idea of a brand-new megadevelopment with jobs that might be inaccessible or not permanent to the neighborhood it’s in isn’t a tenable solution.

“The area itself has always kind of served as a gateway for immigrants and working class people looking to get their start, you know, and there’s still a lot of people like that in the area,” said Eckes. “We want to make sure that they are provided the opportunities and other people that want to come in and build themselves up have those same opportunities. Unfortunately, if the city is successful in what their vision apparently is, it’s not going to be that community. It’s going to be more of a Lincoln Park–style place for the wealthy on the north end and then, you know, the people on the south end being poorer, dirty, suffering more, smaller, with smokestacks.”

Eckes added that heavy reinvestment into the communities already calling a place home can allow them to reinvest in their own neighborhoods and establish a stronger tax base. “If we’re given jobs, if we’re given opportunities, we’re educated, and we have all this, we can be the ones to open up the businesses, or open up the shops, and do other things to help boost up the area, if you will.”

Zettel believes the city needs to be investing more in clean opportunities for the Southeast Side that marry the need for workable jobs with non-polluting industry.

“[We] have got to bring that cleaner stuff to the Southeast Side too. [We] shouldn’t keep perpetuating the history of environmental racism where you say, ‘Okay, so now the North Side’s getting these like clean, innovative, new waves of manufacturing and the South Side gets, you know, the scraps shredder.’ That’s not good for anybody,” Zettel said. “So, you kind of have to look at the whole region and say,, what does environmental justice look like? How do we end environmental racism? And how do you convince people that these new changes in manufacturing are viable?”

Making new changes viable is exactly what The INVERT is trying to sell.

According to Sibley, The INVERT won’t be tied to any one company or industry because it will be a space for many potential tenant companies. “We’re talking about roughly six million square feet of space,” he said. “If you think about the Southeast Side, that community at one point was almost entirely dependent on one industry, and when that went away, so did the economic interest of that community.”

For Eckes, the idea of this kind of innovation—an underground development—is too large of a risk, both for his community and for the environment.

“I don’t see it. There’s no other explanation I could think of for why they need to build underground,” Eckes said. “I mean, we have NorthPoint [warehousing], you know, they’re well above ground, right? Why did he need to build under? It just doesn’t make sense.”

“They’re a startup. What is it, like ninety percent of startups or something like that fail? What you’re talking about is you’re building this giant underground excavated point where you don’t already have customers lined up. There’s no guarantee that you’re going to be successful,” he said. “And if you’re not successful, we’re stuck with this big giant hole.”

According to the INVERT team, they’ve undertaken a deep engagement process within the community to reduce harm in the East Side area, which has been deeply scarred by the injustice of environmental racism and neglected by the city and state.

“It’s certainly been an active space,” Sibley said, referring to the developers’ “Community Engagement Center” at 10548 S. Ewing. “Just to have frank and open dialogues about the project with people…and you know that the response has been very positive. The INVERT team is very interested in listening to all those points of view and gathering input, making adjustments, and that has been extremely helpful.”

“I think sometimes you see in other developments where an application is applied for—there’s an application for development with the City of Chicago, and then after that application is put in place, then sometimes developers go and engage the community. Here, in this case, The INVERT did the opposite. They also inverted that process,” Sibley said.

But it’s this overcommitment to the company’s idea of engagement that, ironically, leaves community members questioning the developers’ intentions, particularly when the project is so financially lucrative.

“This is the first time that a facility has gone to this trouble to win. You know, they throw out the first pitch at the Little League game. They’ve co-sponsored every Music Fest and neighborhood fest. In the neighborhood, they’ve donated money to the high schools. And they aren’t even here yet. I think they want to make it really difficult and make it really confusing for people to like, they want to dominate the narrative,” Bautista said.

Sibley claims that, pending the results of the impact studies, which will assess the impact that construction will have on the site and surrounding communities, as well as feedback they receive from the community, the INVERT team expects to break ground late this year. The development, still very much in the planning phase and not yet brought before the city’s department of Planning and Development, hinges on that feedback.

“People [would] ask us questions early on that we hadn’t had the answer for yet,” Sibley said. “Because it’s so uncommon to actually sit down and have a conversation about an idea before ever putting a shovel in the ground or making a formal application or anything like that. So, when the team didn’t know the answer to the question, they were very open about that. We don’t know. We have to think about that.”

Regardless, Bautista isn’t convinced.

“Ozinga has always been a battle…their mission is not to protect the public health of the community. That’s my mission. Their mission? Their plans? To make money.”

Update 5/26/22: Attribution and link added to the Great Cities Institute’s report.

Cam Rodriguez is a data journalist currently working for education newsroom Chalkbeat, and likes reporting on issues involving local history, infrastructure and communities. This is Cam’s first story for the Weekly.