Over the past year, the city’s Divvy bike share program—one of the largest in North America—has added over a hundred stations across the city, dozens of them on the South Side. A year ago, the last time the Weekly reported on Divvy’s service of the South Side, we found that South Siders accounted for just a twentieth of total riders. At that time, Divvy had recently announced its expansion, so there was some cause for optimism—perhaps the city would successfully replicate the dense network of popular stations in the North Side and portions of the West Side and the statistics would improve.

Now that the expansion has been conducted and the data has come in, the results seem to suggest that such optimism might have been premature. Ridership numbers have not meaningfully improved, and, in some neighborhoods, have actually decreased. Dozens of bike stations across the South Side go virtually unused, recording in many cases as few as a dozen or a half dozen riders every three months. The forty stations added in the South Side expansion saw a total of only about 450 rides in the winter of 2016—an average of eleven rides per station. Meanwhile, Hyde Park, Bridgeport, and Grand Boulevard saw a decrease of almost 1900 riders. Between the winters before and after the expansion, Divvy usage on the South Side increased by a total of just seventy-one rides every three months.

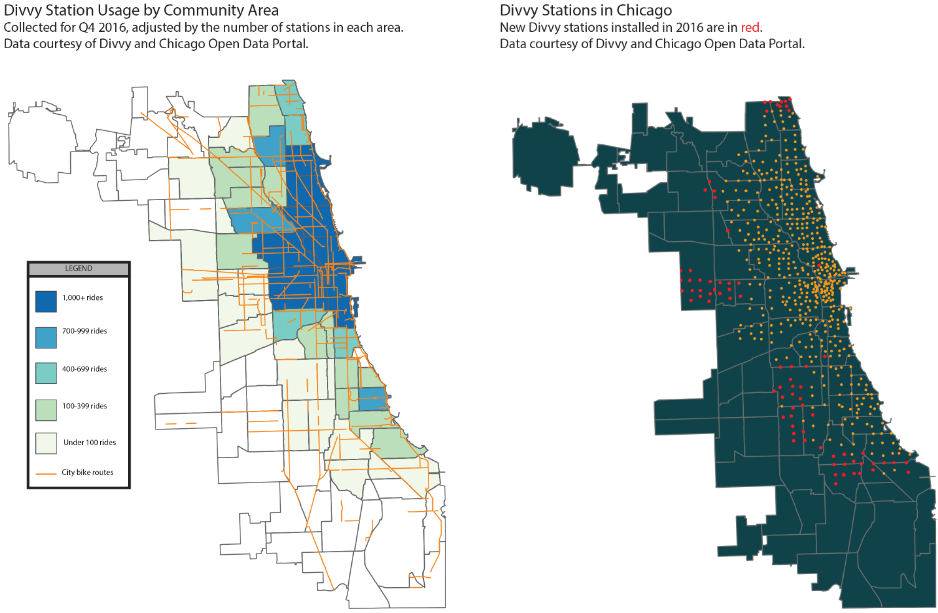

The Divvy expansion, announced in January 2016, added forty stations to the South Side, along with thirty-five stations to the West Side and parts of the North Side, dramatically increasing the number of stations in Back of the Yards, Englewood and Greater Grand Crossing, while introducing the service for the first time to Avalon Park, Chatham, South Chicago, and West Englewood. These seven community areas comprise seven of the nine in Chicago with the lowest ridership per station after the expansion. In the three areas where Divvy already had stations, the expansion caused ridership numbers per station to drop—by margins ranging from thirty to forty-three percent—as the additional stations perhaps diverted traffic from the existing ones. And in the three areas completely new to Divvy, the service seems to have simply not caught on—in Chatham and Avalon Park, the average station had sixteen users over a three month period; in West Englewood, six; in South Chicago, two and a half.

“The numbers in some of the newer service areas on the South and West Sides of the City have not met our expectations,” said Michael Claffey, Director of Public Affairs for the Chicago Department of Transportation (CDOT), which oversees Divvy. But, Claffey insisted, the expansions were a matter of equity. The neighborhoods were selected, said Claffey, “as part of our commitment to spreading the system across the City equitably.”

Equitability rhetoric notwithstanding, the current result is that Divvy stations see virtually no usage in a large swath of the South Side. Excluding the Near South Side, the South Side—defined in this article as the community areas south of the South Branch of the Chicago River or Stevenson Expressway—has a total of 132 stations, scattered throughout most of the area north of 83rd Street and east of Western Avenue. The expansion has not, as of yet, reached South Side neighborhoods such as Pullman, Roseland, Beverly, Chicago Lawn, or Gage Park. Taken as a whole, this portion of the city saw just over thirty thousand Divvy rides in the final quarter of 2016—or about 230 per station. This is about a fifth of the Chicagoland average (approximately twelve hundred rides per station, although this is skewed by the dense network of stations in the Loop and the Near North Side), and is roughly comparable with numbers found in community areas along the outskirts of the Northwest Side—neighborhoods like North Park, Irving Park, and Hermosa, into which Divvy is also expanding. But these overall low numbers obscure the matter somewhat. The reality of Divvy usage rates on the South Side is not that they are consistently low, but that they vary between neighborhoods. Divvy sees moderately high usage in a few discrete areas, moderately low usage in a handful of other areas, and virtually no usage in the majority of the South Side.

That is to say, there are areas in which statistics are promising. Hyde Park is one of the more popular community areas in the city for Divvy, and Douglas is not far behind, with the two areas boasting, respectively, around nine hundred and seven hundred riders each per station. The most popular station on the South Side is #423, facing the Regenstein Library on the campus of the University of Chicago; the second most popular station is #237, at Martin Luther King Jr. Drive and 29th, in the shadows of the Prairie Shores apartment complex. Both of these stations saw over a thousand riders in the final three months of 2016, as did several other stations in Hyde Park and stations on the campus of Illinois Institute of Technology, by Pier 31, in Chinatown, and in northern Woodlawn. And the neighborhoods around Hyde Park and adjacent to northern Bronzeville have shown relative promise: stations in Chinatown, Bridgeport, and Kenwood see ridership figures that are well below the city average but above the average for the South Side. It’s not hard to imagine robust Divvy ridership in the near future in the relatively dense and socioeconomically diverse portions of the northern South Side, along the lakeshore north of Jackson Park, and around the UofC. However, these areas constitute just a small portion of the South Side as a whole.

Forty-five Divvy stations are in Bridgeport, Armour Square, Douglas, Hyde Park, and Kenwood. Add in the very popular station in Woodlawn at 60th and Ellis, and you have forty-six stations. Though constituting just thirty-five percent of total South Side Divvy stations, these stations account for about eighty-five percent of all South Side Divvy usage. The remaining eighty-six stations, accounting for the great majority of Divvy’s coverage of the South Side, had between them only 4800 rides in the last three months of 2016, or an average of just over fifty rides per station. There is some internal variation in this vast portion of Chicago: the Divvy station by the Garfield stop on the Green Line recorded close to four hundred rides, and stations by the DuSable Museum in Washington Park and off of Cottage Grove in Grand Boulevard also reported over a hundred rides. On the other hand, no fewer than thirty-eight stations averaged fewer than twelve rides in the fourth quarter of 2016—less than a ride a week.

These numbers suggest that the obstacles to a successful bike share program in parts of the South Side may have more to do with infrastructural inequities in South Side neighborhoods than with Divvy’s failure to offer a suitable bike network. While it could reasonably be argued last year that Divvy’s sparse network was the cause of low ridership in much of the South Side, it is no longer the case that Divvy’s network is sparse in places like Englewood, West Englewood, South Shore, and several other community areas on the South Side. Englewood, for instance, has twice as dense a grid of Divvy stations as the new expansion in Evanston, but Divvy sees forty times as much use in Evanston as it does in Englewood, or fifteen times when adjusted for population. South Shore has a similar density of stations to Logan Square, but Divvy is twenty-eight times as popular in Logan Square, or eighteen when adjusted for population.

There are a few reasons why Divvy’s current methods of outreach have not yet been successful across the city. Data from 2014—before a single Divvy bike station was installed on the South Side—showed that neighborhoods like Hyde Park and Armour Square, where Divvy is relatively popular, had considerably higher rates of bike commuting than neighborhoods like West Englewood and Chatham, where Divvy is now struggling. Bike lanes and infrastructure in general are sparser on the South Side than on the North or the Northwest Side—the South Side is over five times larger than the North Side by area, yet boasts eighty-six miles of bike lanes to the North Side’s sixty-one miles—and the inland portions of the South Side boast no long bike paths like the Lakefront Trail, Bloomingdale Trail, and the North Shore Channel Trail. Black and Latinx neighborhoods have also long been subject to discriminatory ticketing practices from the Chicago Police Department, a March Tribune investigation found, prompting Black cycling activists to fight back and think about filing a lawsuit.

Another simple explanation is geographical: the West Englewood labor force, for instance, is concentrated either outside of Chicago or downtown, a pattern mirrored by most of the South Side, so it would be infeasible for most residents to bike to work. The cost of a Divvy membership also remains out of reach for many South Siders; median household incomes are twice as high in Evanston as in Englewood, seventy percent higher in Logan Square than in South Shore, and an annual Divvy membership costs $99 a year and requires a debit or credit card—and, as Daniel Kay Hertz, a writer on urban issues, points out, is also entirely disconnected from Ventra, the city’s main transit payment system.

To that end, Divvy is attempting to address some of the socioeconomic factors at work. The Divvy for Everyone (D4E) program, for instance, allows a one-time $5 annual membership (and discounted $50 second-year memberships)—that can be paid in cash for those lacking credit or debit cards—for residents of Chicago under certain income thresholds. The D4E program is available to residents of households making below 300 percent of the federal poverty line—approximately forty eight percent of Chicago, but according to Claffey, approximately 2,200 residents are enrolled in D4E, demonstrating significant untapped potential for D4E enrollment and relatively lackluster growth over the last year; it has grown by just 1,100 residents, according to numbers provided by the city. “The city has succeeded in making Divvy affordable,” said Claffey, “but we are still working to demonstrate Divvy’s value to some Chicagoans.”

The numbers are “encouraging, but there’s clearly a much, much bigger potential user base for whom D4E should be a great program,” Hertz, who contributes to the Weekly, said.

CDOT is at work trying to effect its demonstration, according to Claffey, referencing a “new Divvy outreach team” that would be employed “to learn from residents about the challenges they face and to educate them” about how “Divvy can be part of the solution.”

Given the low ridership associated with the expansion this past summer, it may also be the case that Divvy would be best served by focusing investments on the portions of the South Side that already see relatively high levels of ridership but are not as saturated by Divvy stations as Hyde Park—areas such as the side streets off MLK Drive between 20th and 40th Streets, northern Woodlawn, stations along the Green Line and the Red Line, and the lakeshore. In general, according to Hertz, the city would be well-served by building more bike lanes and trails all over the South Side in order to encourage biking and make it safer for all cyclists. In addition to helping the existing pool of cyclists on the South Side, such infrastructure might encourage more residents to try Divvy bikes or even to enroll as members. In the end, the city needs to reconcile the “conflict between increasing the ‘area served’ by Divvy and optimizing the density of Divvy stations in the areas that are served,” Hertz said—and improve Divvy service for everyone.

Sam Stecklow contributed reporting.

Did you like this article? Support local journalism by donating to South Side Weekly today.