Labor,” in the Chicago context, is often spoken of as a singular entity. Headlines from the Tribune’s archive illustrate this use: “labor steps up,” “labor needs to,” “Big Labor’s expectations.” Even the Weekly isn’t immune: our story last year about the 125th anniversary of the Pullman strike was titled “Remembering Labor’s History.”

Three recent Chicago-focused books complicate that usage, reminding us that the collection of unions we call organized labor has evolved through history. Who has the right to be a part of the labor movement has often been a contentious question. Union leaders often disagreed, sometimes violently, with each other and with their membership about the direction of the labor movement, and these conflicts shaped what we now simply refer to as “labor.”

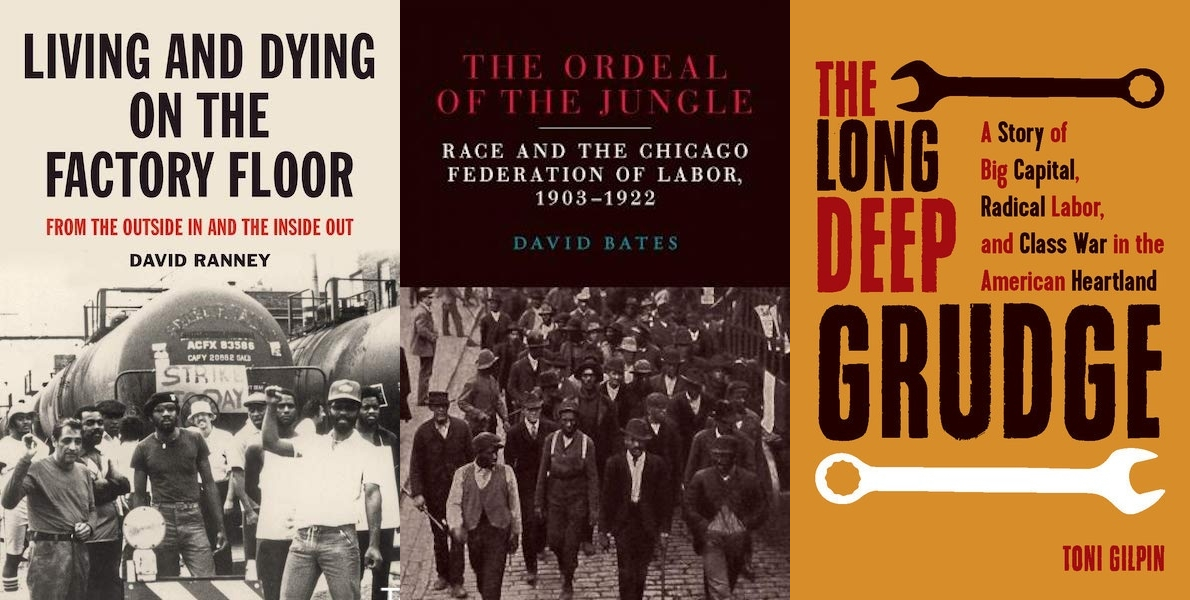

The Ordeal of the Jungle, from David Bates, an assistant professor of history at Concordia University Chicago in the west suburbs, chronicles the Chicago Federation of Labor’s efforts to build a multiracial coalition in the stockyards of 1910s Chicago. The Long Deep Grudge, by labor historian and activist Toni Gilpin, is a project both academic and personal: Gilpin is the daughter of a Farm Equipment Workers Union (FE) organizer and wrote her PhD thesis on the union, later adapting that thesis into her book. Living and Dying on the Factory Floor, a memoir by University of Illinois at Chicago urban planning and policy professor emeritus David Ranney, paints a grimmer and more personal picture of labor, discussing his time working in factories on Chicago’s Southeast Side between 1976 and 1982.

The books focus on different industries and periods of time; the FE got started more than a decade after the epilogue of Bates’s book, and winked out of history more than two decades before Ranney left the University of Iowa for the Southeast Side. But each highlights different approaches to a fundamental question that continues to dog the labor movement: how to convince workers, divided by lines of race and ethnicity, that they have a common interest worth fighting for?

The Ordeal of the Jungle, first chronologically, investigates the Chicago Federation of Labor’s (CFL) attempt to solve that age-old problem. Through archival documents chronicling the perspectives of union leaders and rank and file workers, as well as their opponents, Bates documents the impact of race on efforts to organize Chicago’s great steel plants and stockyards in the late 1910s.

The CFL seems to have genuinely wanted to organize a union that included both Black and white workers, and made substantial progress toward that goal. Bates quotes CFL attorney Frank Walsh proclaiming that “the white man’s unions are going to show that they are as loyal to the rights of the [Black] man as they are to a white man.” Bates, however, takes care to demonstrate that this was not just the product of a newfound concern for civil rights: his first chapter recounts a 1904 stockyards strike that came to be defined by “violent reprisals” against Black strikebreakers, despite as much as eighty-five percent of strikebreakers being white. Uniting stockyard workers across racial lines would break down what Walsh called “the last barrier in [the stockyard bosses’] defense against the American working men.” Over the objections of the American Federation of Labor, its parent organization, which objected to any organization that included unskilled workers, the CFL organized the packing workers, Black and white, under the banner of the Stockyards Labor Council (SLC).

[Get the Weekly in your mailbox. Subscribe to the print edition today.]

But the organization of the SLC would ultimately prove to be its undoing. Unskilled workers were organized by “neighborhood-based organizations,” which Bates describes as “local unions with ties to the workers’ ethnic and ward communities.” These neighborhoods allowed the CFL to move beyond the traditional boundaries of craft unionism, uniting workers across their specific units in the stockyards. They also allowed the union to expand its presence beyond the shop floor: Local 651, the union representing workers from the Black Belt, also opened a cooperative store in the neighborhood to strengthen ties between workers and the community.

By organizing workers along neighborhood boundaries, however, the CFL had effectively created a segregated union. Although Local 651 was theoretically equal to any other neighborhood local, it represented a segregated Black neighborhood—now part of Bronzeville—and quickly became known as Colored Local 651. The union was soon considered a “Jim Crow local,” a reputation that, first and foremost, undermined its efforts to organize Black workers.

Packing bosses were more than happy to exploit this reputation in order to subvert the union’s organizing efforts. The packers sponsored Black community institutions such as the Wabash Avenue YMCA, hired Black “agitators” to promote anti-union sentiment among workers, and possibly sponsored the creation of a rival labor union, all with the goal of making sure that, despite the CFL’s efforts, the Black workforce would remain largely non-union.

Tensions came to a head with the race riot of 1919. Many Chicagoans are familiar with the story of Eugene Williams, who swam across an invisible line dividing what was then the 29th Street Beach and was stoned and drowned by white beachgoers. This sparked more than a week of racial violence, which ended in thirty-eight dead and more than five hundred injured. Following the riot, Black workers (still mostly non-union) went back to the stockyards under the eye of police and state militiamen, provoking ire—and a wildcat strike—among white union members, who harbored both racial resentments and bitter memories of past instances of police violence against striking union workers. Black workers were largely happy to have police protection after the riots, and were pushed away from unions by the CFL’s eventual support for the wildcat strike. In 1920, the CFL estimated that “the percentage of the organized colored workers has been very insignificant.”

By the early 1920s, the CFL’s efforts to organize Chicago’s industrial workers had collapsed. A steel strike in 1919 and a stockyards strike in 1921-22 followed a familiar pattern: white workers went on strike, bosses broke the strike with Black strikebreakers, and the result was a defeat for the union. In the stockyards, the eight-hour day was lengthened to ten hours, and both steel and packing would remain effectively non-union professions into the 1930s.

Bates concludes by contrasting the CFL’s failures with the success of the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO), which successfully pursued a campaign of interracial organizing in Chicago’s steel mills and packinghouses in the 1930s. The CIO, Bates writes, “viewed civil rights and racial justice as a central part of its mission,” which resulted in a successful interracial union (with some help from the federal government).

Beyond the stockyards, only two other Chicago companies employed more than a thousand Black workers during the CFL’s first interracial organizing campaign: Sears, Roebuck and Co., and International Harvester. The progressive, interracial union movement that failed to take root in 1910s Chicago would find considerably more success through an organizing campaign at the latter, the subject of Gilpin’s The Long Deep Grudge.

The book draws its title from Nelson Algren’s Chicago: City on the Make, and its telling of the history of the United Farm Equipment and Metal Workers (FE) begins at the focal point of Chicago’s labor history: Haymarket. The road that led to the Haymarket massacre began with a campaign for an eight-hour day at the McCormick Reaper Works, which would eventually become International Harvester (IH). That history would inspire the men who eventually organized an independent union at IH in the 1930s; banners bearing the last words of anarchist leader August Spies, executed following the events at Haymarket, proclaimed that the “time when our silence is more powerful than the voices you are strangling today” had finally come.

Succeeding where the Haymarket martyrs and generations of other union organizers had failed required a new kind of union, and a new approach to organizing. John L. Lewis, president of the United Mine Workers and founder of the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO), called organizing at IH “the hardest job I know of,” in part because the McCormick family were pioneers of union-busting. IH was one of the first companies to introduce “works councils,” company unions that offered a taste of workplace democracy while never directly opposing management.

This façade of democracy was not so much shattered as co-opted. In the early 1930s, a handful of Communist Party activists at McCormick’s Tractor Works connected with a group of dissatisfied members of the plant’s works council, eventually developing the council into an independent union, the FE, that joined the CIO in 1937. In 1938, an election overseen by the new National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) saw an overwhelming victory for the FE, creating FE Local 101. The new union quickly grew, relying on what Gilpin calls a “rank-and-file structure” and a pledge to “advocate for skilled jobs for Black workers” to make inroads with workers at other IH plants. By the fall of 1941, the FE represented 20,000 IH workers, including employees at IH’s West Pullman plant and the company’s “toughest plant,” McCormick Works. In May of 1942, the company signed a national contract with the FE, securing wage increases, a grievance procedure, and a union shop agreement.

Signing the contract wasn’t the end of the struggle for the FE. Director of Organization Milt Burns declared that “the philosophy of our union was that management had no right to exist.” This combative attitude, especially apparent when contrasted with unions that valued productivity growth and a positive labor-management relationship, meant that this philosophy appeared on the shop floor as “a different conception of what effective day-to-day union representation looked like.” The FE challenged management at every turn, and in doing so won “the fierce and sustained loyalty” of the rank and file.

As we saw with the CFL, the views of union leadership alone cannot make a successful integrated union; the best designs of progressive leaders can be undermined by the lack of any substantial buy-in from rank and file members. The FE, however, was different: by winning the confidence of the membership, they were able to overcome the prejudices of the workforce in order to develop a vision of a fair workplace that was appealing to both white and Black workers.

While the FE was born in Chicago, their most impressive interracial organizing came 200 miles south, in Louisville. The largely non-union South offered IH an opportunity to escape the FE while taking advantage of the “Southern differential,” the lower manufacturing wages prevalent throughout the region. IH also took an additional step to ensure the loyalty of their workforce: IH CEO Fowler McCormick declared the plant an “experiment in biracial industrialism,” hiring Black workers throughout the plant. In a city where, as eventual FE organizer Sterling Neal wrote, it was rare “for Negroes to hold any position above the status of janitor or laborer,” this progressive policy made IH genuinely stand out as one of Louisville’s better employers for Black workers.

Attempting to organize a union that included both newly-empowered Black workers and workers who FE organizer Jim Wright, who is Black, described as “real racist, I mean real racist” would prove to be the FE’s biggest challenge yet. One option would have been downplaying race, as the CFL did in Chicago, treating Black and white workers as workers facing the same challenges. Instead, the FE consciously “built a commitment to racial equality into the DNA of the local.” The FE was competing with the United Autoworkers (UAW) and American Federation of Labor (AFL) to represent plant workers, but the FE was the only one of the three to prioritize interracial organizing. The other two, an FE pamphlet wrote, were “‘organizing’ in the traditional southern fashion … calling the white workers aside and promising them that as soon as they won bargaining rights, the Negroes on machines would be put back on brooms ‘where they belonged.’” The FE, by contrast, believed that “the only way to beat Harvester’s low wages was to unite the Negro and white workers.” The union hired a Black organizer in Louisville and, in 1946, elected two Black members to the union’s eleven-member executive board. In the summer of 1947, the FE bested both rivals, forming Local 236 to represent workers at the Louisville plant.

Within two months, the FE was on strike in Louisville. The demand was an end to the “Southern differential,” challenging their status as “second-class citizens” in Harvester’s vast network of plants. While they didn’t win all that they asked for, the union was victorious in raising wages for plant workers, cementing their place in Louisville. Only a handful of white workers, and no Black workers, crossed the picket line.

This display of unity, and the everyday confrontations between the union and management, helped build interracial solidarity as “not an abstract construct but a daily practice that delivered tangible and immediate benefits to the union membership.” Gilpin quotes civil rights activist Anne Braden as writing that every Local 236 meeting was marked by someone talking about “the reason we’re so strong and we can win… is because we stick together, Black and white. Let them, they attack a Black worker and we’re there to do something, we’re going to walk out of the plant—this is the reason we’ve got the strong union.”

This solidarity extended beyond the doors of the plant. Unlike in 1910s Chicago, Black and white workers weren’t just part of the same union—they saw their struggles and fortunes as linked together. Braden observed that “it was the usual thing to see Negro and white members sitting together… many of the same white men visited in the Negro unionists’ homes, and the Negroes went to white members’ homes.” Wright ascribed this to “a religious feeling of them sticking together.” This feeling pervaded beyond the walls of the factory: interracial contingents of FE workers picnicked in segregated parks, visited the lobbies of segregated hotels, and marched to end segregation in hospitals as part of what was referred to as a “constant campaign” for equality.

For all their success, larger forces would collaborate to undermine and destroy the FE. The decline began when the union defied Section 9(h) of the 1947 Taft-Hartley Act, which required union leaders to sign affidavits that they were not communists in order to enjoy the protections of the NLRB. The UAW launched an organizing drive at an FE-represented Caterpillar plant in Peoria, and since the FE wasn’t in compliance with the NLRB’s rules, the options in the election were the UAW or “no union.” Almost immediately, they lost a quarter of their membership. One year later, the CIO expelled the FE and a handful of other left-leaning unions.

The next year marked an ideological defeat: “The Treaty of Detroit,” an agreement between the UAW and General Motors, laid out an alternative model of unionism. UAW leader Walter Reuther committed the union to a “politics of productivity,” accepting management’s right to exist and focusing on negotiating a contract that delivered substantial wage and pension benefits. In exchange for a contract that largely met their demands, the UAW agreed to “a long stretch of well-compensated peace,” rather than the walkouts and slowdowns that were a regular feature in FE plants.

Despite the FE’s accomplishments, it was the much larger UAW that eventually carried the day. A disastrous 1952 strike undermined the FE’s claim that a “strong picket line is the best negotiator,” and with its influence and capacity waning, the FE admitted defeat. Despite some resistance from the rank and file, the FE merged with the UAW in 1955.

It was the UAW’s attitude toward unionism that prevailed through 1976, when Ranney left a tenured professorship in urban planning at the University of Iowa to work in the factories of Southeast Chicago, as he chronicles in Living and Dying on the Factory Floor. Ranney initially moved to Chicago to volunteer at a pro bono legal clinic, the Workers’ Rights Center. At the time, he was also involved with a small left-wing group known as the Sojourner Truth Organization (STO) that placed an “emphasis on political work with those in the factories,” believing that workplace actions would escalate into the eventual overthrow of capitalism. For Ranney himself, however, it was less ideology and more financial necessity, his savings having dried up, that led him to apply for work making everything from shortening to paper cups to railroad cars.

Ranney’s book is explicitly written “not as a memoir.” It’s written in the first person and in the present tense, and is meant simply as an “account of life and even death on the factory floor.” Much of it reads like a novel, a radically different form compared to the academic labor histories of Bates and Gilpin. Ranney’s personal account of the factories, however, serves to underscore many of the themes raised generally by the other two authors. It is one thing to hear from Gilpin about unions making a turn toward collaboration with management, for instance, and quite another to read a first-person account of what that looks like twenty years afterwards.

The most compelling part of the book is an account of a wildcat strike at Chicago Shortening, a small, majority-Black plant where Ranney worked as a welder for about a year and a half. The plant has a union, the Amalgamated Meat Cutters, but that means little for the workers; when the union’s business representative stops by to announce the union is renegotiating their contract, the response is uniformly hostile. Unlike the FE or even the CFL, this union is an antagonist. One of the workers explains that the last contract was “shit,” that “the company pays off the union just like they pay off everyone else,” and that the union and company are both an elaborate front to launder money for the mafia. The mafia ties remain unclear, but the corruption doesn’t: despite none of the workers admitting to voting for the union’s new contract, it passes nevertheless.

The workers agree unanimously to strike if the contract isn’t canceled. Ranney is called up to the company president’s office, where a union business rep accuses him of “stirring up” the Black workers, then assaults him. The workers respond with a spontaneous walkout, and the strike begins. It drags on for ten weeks, notching a handful of victories—Charles Sanders, one of the strike’s leaders, persuades a railroad engineer delivering a load of shortening to respect the picket line—but ultimately collapses. Binding arbitration is a farce, with the union and company lawyers working with each other while ignoring the complaints from the workers. It ends on a tragic note: Sanders, hired back because he had been on disability leave when the strike began, was stabbed to death by a scab.

The picket line is the site of some unusual alliances, similar to the unprecedented integration at the Louisville FE local. Puerto Rican nationalists and a group of Iranian student activists make appearances; one worker notes that the Shah of Iran “sounds like a bigger motherfucker than the guy we got to deal with.” Perhaps the most intriguing character on the line is Heinz, a self-proclaimed Nazi who wears a leather jacket with swastikas and Confederate flag patches. Despite this, Heinz becomes one of the most militant strikers, at one point threatening to shoot out the tires of the tanker trucks that supply the factory.

The shortening plant was informally segregated: the Black workers take their breaks in the locker room, the Mexican workers sit near the fill line, and the handful of white workers have a separate, better-furnished locker room. Ranney takes breaks with the non-white workers, and finds that the Mexican workers “think the [Blacks] are lazy drunkards,” while the Black workers “believe [the Mexican workers] are all ‘illegals’.” As the strike winds on, however, those barriers break down; workers (including even Heinz) picnic in the Indiana Dunes over the Fourth of July, mixing freely. It’s a callback to the FE’s strategy, where a militant labor movement can become a common cause for Black, Mexican, and white workers, social barriers can break down. At the same time, the ultimate failure of the strike demonstrates how much things have changed since the FE ran the show.

The book continues through a handful of other factories with names like Mead Packaging and Thrall Car, and includes a failed unionization drive at Solo Cup. That story ends with a chance encounter at a party hosted by a UIC professor, which results in Ranney returning to academia. A brief but moving chapter follows when Ranney returns, thirty-five years later, to a South Chicago that now feels abandoned. The steel mills are gone, the restaurants are closed, and many residents have lost their homes after the housing crash. One of the plants where he used to work is now an EPA Superfund site.

Ranney then goes on to explain his impetus for writing the book: frustration with politicians’s promises to “bring back middle-class jobs.” He notes that the decline in manufacturing that produced this devastation was “a deliberate strategy on the part of corporations around the world” to increase profits through automation and offshoring. Ensuring that people can make a living wage, therefore, will require more than just relocating a few factories—it requires “mov[ing] beyond capitalism.”

Some indication of how we might get there comes through the strike at Chicago Shortening. The unions Ranney experienced had “traded labor peace for a share in the post–World War II prosperity,” and were unwilling to fight for the Black, Latinx, and women workers largely left out of that bargain. Racism and racial resentment, encouraged by the company, structured the relationship between workers. Once the strike began, however, that faded away; “the meaning of class and the potential of class solidarity became self-evident.” While Ranney doesn’t lay out a blueprint, he does mention the tantalizing possibility that, “had the struggle prevailed, new ‘permanencies’ would have governed day-to-day behavior.” “A broader struggle for a new society,” he suggests, could affect human nature in a similar manner.

While each of the three histories addresses a different time period, industry and location, all of them highlight different approaches for the labor movement in seeking to install a sense of solidarity in a divided workforce. There is a clear line from the halting and ultimately unsuccessful efforts of the Stockyards Labor Council to the aggressive militancy that both built and ultimately undid the FE, leading to the complacent unions that feature in Ranney’s book. If there is a theme that unites all of them, it is the importance of a sense of solidarity in the rank-and-file, which undid the CFL’s campaign just as effectively as it energized the FE’s work and empowered the wildcat strike at Chicago Shortening. All three books provide a valuable perspective on labor organizing and Chicago’s history, and each hints, in its own way, at a viable path forward for the labor movement.

Listen to David Bates discuss his work on a February episode of the Steel Revolution’s Podcast at sswk.ly/OrdealOfTheJungleTalk

Watch an author talk between Toni Gilpin and Lake Forest College history professor Cristina Groger, hosted last week by Chicago DSA, Haymarket Books, and Pilsen Community Books, at sswk.ly/LongDeepGrudgeTalk

Watch an author talk with David Ranney hosted by UIC’s Great Cities Institute at the Jane Addams Hull-House Museum recorded by CAN TV last April at sswk.ly/LivingAndDyingTalk

Sam Joyce is the nature editor of the Weekly. He last covered the election for the Metropolitan Water Reclamation District.