Chicago is considered the birthplace of the environmental justice movement—but mayoral candidates have never really been grilled about how they would address the issue.

This year, the Chicago Food Policy Action Council (CFPAC) and several community groups hosted a food- and environmental justice–focused forum at the South Shore Cultural Center on February 15, likely the first forum of its kind in the city, according to Anton Seals Jr, CFPAC board member and lead steward and cofounder of Grow Greater Englewood, one of the forum’s co-sponsors.

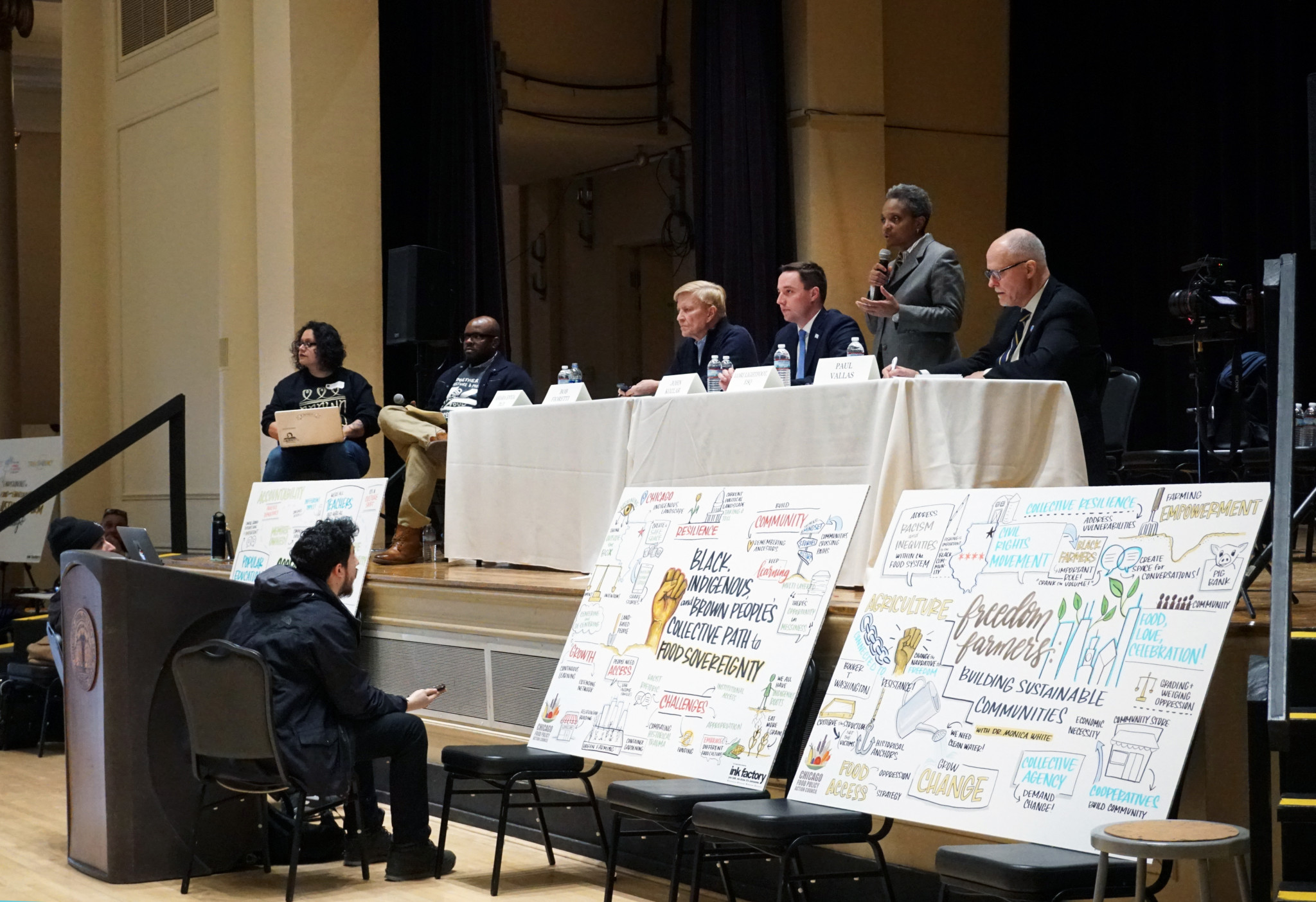

Only five candidates showed up to the forum: John Kozlar, Lori Lightfoot, Paul Vallas, Bob Fioretti, and La Shawn Ford. (The original forum had been rescheduled because of extreme weather.) At the beginning of the event, Seals introduced the topics of food and environmental justice as “crucial civil rights issues that have historically and continue to disproportionately impact disadvantaged and low-income communities of color.” Kim Wasserman-Nieto, executive director of Little Village Environmental Justice Organization (LVEJO), introduced questions alongside Seals. All of the questions concerned addressing these social inequalities.

In 2017, the city passed a resolution to adopt the Good Food Purchasing Program, a national initiative to leverage government spending power to create sustainable food systems. CFPAC led efforts to lobby the city to adopt the program, and executive director Cooley hopes to see the next mayor prioritize the program, which currently involves four agencies and five city departments. Local organizations will play a role, too.

The forum was co-sponsored by many community groups, including Chicago Environmental Justice Network, Chicago South East Side Coalition To Ban Petcoke, Food Chain Workers Alliance, Ixchel (Cicero/Berwyn), Street Vendors Association of Chicago, and the Southeast Environmental Task Force, many of which are part of the Good Food Purchasing Program effort.

Each candidate was in support of flushing out the city’s commitment to the program. Lightfoot called for getting private institutions to join. (Currently, the program only applies to public agencies.) Ford advocated using the program to bring more healthy food into schools. “Many times we see our children not performing well simply because they’re not eating well. And many times the only meal that students get for the day, whether it’s breakfast, lunch, or dinner, is at school,” Ford said. “When young people learn how to eat, they teach their parents.”

Candidates were also asked how they would support emerging farmers and entrepreneurs in ag-related fields, especially Black and brown farmers, and encourage more cooperative business ownership. Chicago is known as one of the country’s leading urban agriculture cities, with over 800 urban agriculture sites, according to the Chicago Urban Agriculture Mapping Project. Last November, state lawmakers overrode then-Governor Bruce Rauner’s veto of a bill that allows Illinois cities to establish urban agriculture zones. Sales tax revenue from agricultural sales in these zones will be put into a fund to be allocated to programs or initiatives of the zone members’ choosing.

The city has 32,000 vacant lots, according to the Institute for Housing Studies at DePaul University. Moderators wanted to know how candidates might use this land to revitalize neighborhoods through community gardens, urban farms, and other initiatives, especially as an alternative to development projects that threaten to displace long-term residents and renters.

Both Ford and Lightfoot were passionate about urban agriculture providing jobs as pathways to economic stability. Vallas had a plan to turn an empty school into an urban agriculture school for adults.

Fioretti called for creating better online portals so that people can access information about how to purchase and develop land. The city sells many vacant lots through its Large Lots program, but this land is only open to people who are already landowners, and “there isn’t necessarily clear transparent processes for transferring land,” according to Cooley. The current system also makes it difficult for communities to cooperatively own and develop these areas.

Kozlar failed to answer the question at all, instead taking a poll of the audience to see how many were registered to vote (most) and how many knew who they were voting for (very few). In the time he had left, he announced his website.

Kozlar was also the only candidate to express hesitation about legalized recreational marijuana, which was brought up by moderators as a potential way to boost a Black- and brown-owned marijuana cultivation industry. He implied it would become a gateway drug for youth, a stance that elicited boos from the audience. Fioretti was similarly skeptical about the opportunities legalized marijuana might create. “They’ve always decided how they’re divvying it up,” he said, referring to the power of legislators to vet marijuana licensing. Vallas, Ford, and Lightfoot were in support of ensuring revenue would benefit communities hardest hit by the war on drugs.

Moderators grilled the candidates on how they would ensure community members would have a seat at the table for agricultural projects and other development. Industrial development is often fast-tracked without prior approval or input from residents, Wasserman-Nieto said. It often leads to cumulative negative effects, such as air, water, and noise pollution, and the prevalence of hazards, she said.

None of the candidates provided a thorough plan to involve community input, though they each had their own riff. Ford summarized the problem, saying every candidate believes in “open government,” and the problem comes down to implementation, but he failed to outline what he himself would do. Fioretti sounded ambitious, saying he would have community meetings with every neighborhood before any project was passed.

Reallocating TIF funds to undeveloped areas was a popular response from most candidates, as was establishing mayoral term limits; Lightfoot and Vallas pushed for limiting aldermanic prerogative. Vallas also mentioned the importance of having community benefits agreements, an agreement between developers and residents, for incoming projects such as the Obama Presidential Center (OPC). The OPC is likely to displace more renters than homeowners, so increasing access to affordable housing is part of his platform, he said.

Overall, candidates seemed hesitant to address environmental and food justice policies head-on, instead pivoting on each question to provide vague, bigger-picture statements.

Kozlar in particular tended to use the platform to express outrage at the city’s history of corruption in elections, which he considers “elitist.” In his opening statement, he claimed to be “concerned about the future of our city,” but didn’t mention the words “environment,” “food,” or “justice.” Like many other candidates, “public safety” is another key part of his platform, referring mainly to gun control and police accountability; yet he failed to extend this analysis to address the slower violence of environmental injustice.

Most candidates’ platforms do not explicitly use the words “environmental justice” or “food justice,” despite the urgency of some of the issues that would fall into these categories, like the lead water crisis. Chicago has the most lead water lines in the country—360,000, according to the Chicago Department of Water Management—and a recent Tribune data analysis estimated that seventy percent of homes tested have some lead in their water. Though fixing lead pipes is mentioned in all five of these candidates’ online platforms, only Lightfoot and Vallas touched on the issue in their opening statements.

But Toni Preckwinkle, Amara Enyia, and Susana Mendoza, none of whom attended the forum, use the term “environmental justice” in their platforms. Each of their websites mention green jobs and replacing lead pipes as priorities, among other issues such as improving recycling infrastructure and green space. Preckwinkle, who was recently endorsed by Sierra Club, and Mendoza call for transitioning the city to 100 percent renewable energy by 2035. Though each of their plans leave room for specifics, Preckwinkle focuses on making the CTA run on electricity, while Mendoza would create a competitive bidding process among city agencies to subsidize renewable energy credits. Both would pursue utility companies that run on renewable energy, and boosting the solar industry.

Enyia aligns herself with the Green New Deal, and dubs her lead pipe replacement initiative a Blue New Deal, which would help offset the costs of replacing lead pipes. Currently, residents and landlords must pay out of pocket, a cost of $2,500 to $8,000 per home. Vallas’s and Preckwinkle’s platforms call for a similar plan.

Though this did not come up as a question, some candidates, including Lightfoot and Vallas, found ways to articulate their plans to reinstate the city’s Department of Environment, shuttered in 2011 to save the city money.

Vallas added that he would like to have a reinstated Department of Environment overseen by an advisory council. Ford said he would “not trust my expertise” on environmental issues, but would instead ask for input from environmental experts. Enyia’s platform calls for not only reinstating the Department but also calling it the Department of Environmental Justice, the only candidate to suggest such a change.

When prompted to give closing remarks, none of the candidates touched on environmental justice. Instead, they made pleas to voters to educate themselves and vote for a candidate committed to ending corruption.

For Pamela Saindon, Vice President and chair of the Political Action Committee of the NAACP Chicago Southside Branch, which helped contribute questions to the forum, this election is an opportunity for voters who care about environmental justice.

“We are not aware of any mayor that has adequately addressed this issue in recent history,” Saindon said. “The next mayor must ensure that environmental justice is a priority and issues associated to it are being addressed as well as create innovative ideas to combat environmental racism.”

Lafayette Ford, sixty-eight, attended the forum to learn more about the candidates and decide who to vote for. A resident of South Shore for over twenty-three years, he is the president of South Shore Preservation and Planning Coalition and a boardmember of Black United Fund of Illinois and of South Shore Works.

He said that he’s concerned about the Obama Center and other development projects displacing residents on the South Side.

“South Shore does not have as much vacant land [as Washington Park] but we do have an interest in what happens with the encouragement of what type of development,” he said.

CFPAC is already planning another environmental justice forum for the inevitable mayoral runoff, Cooley said. “There’s very few politicians who can talk about food justice and environmental justice in a very sophisticated way, so the more we can do to get the messaging out, the better.”

Amelia Diehl is a writer and artist born in Hyde Park and raised in Ann Arbor, MI. She is a former intern at In These Times magazine. This is her first piece for the Weekly.