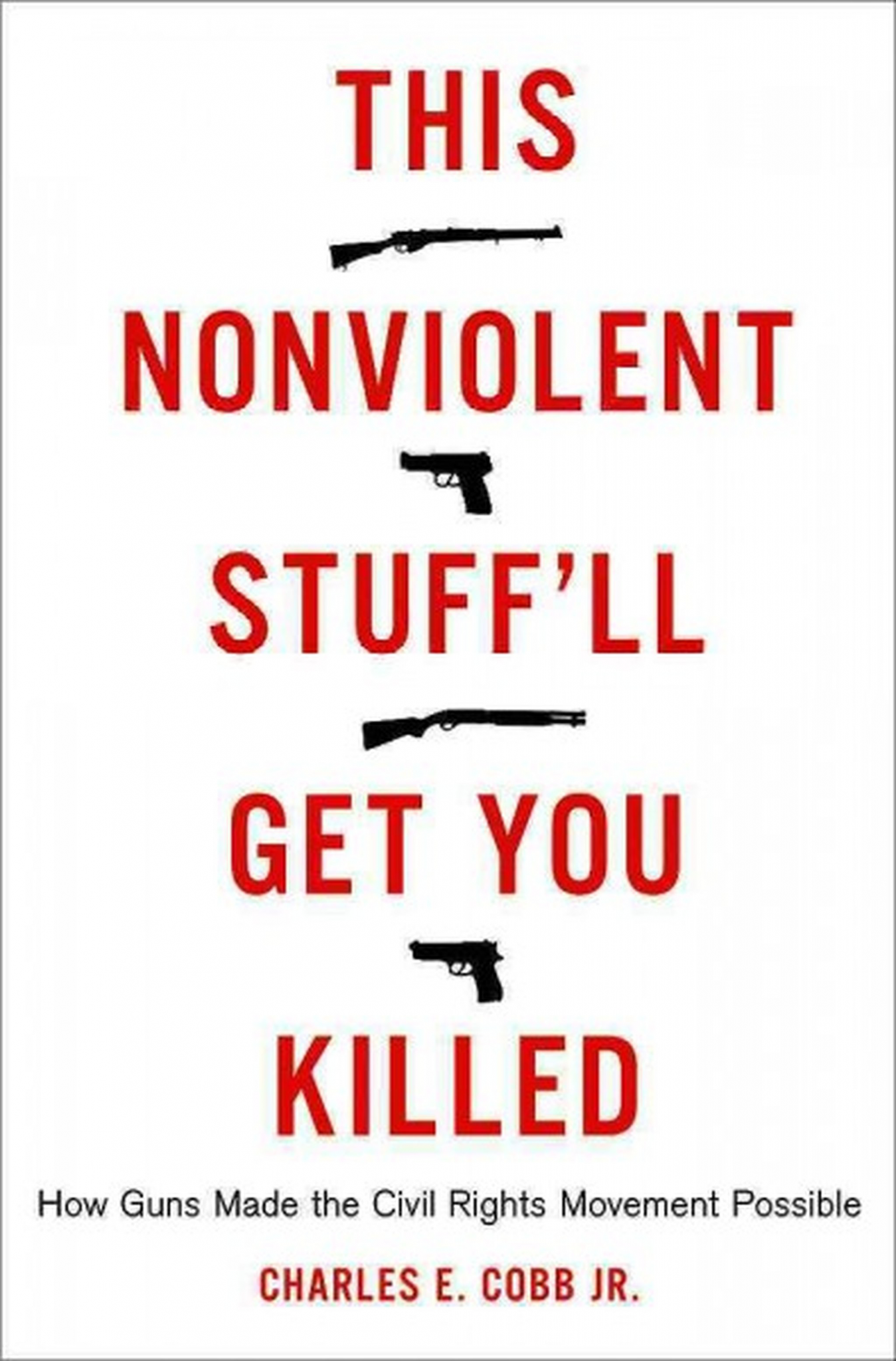

In his epilogue to This Nonviolent Stuff’ll Get You Killed, journalist Charles E. Cobb Jr. describes how Stokely Carmichael, one of the founders of the Black Panther Party, was roundly condemned by other leaders in the civil rights movement after his call for Black Power in 1966. The founding of the Black Panther Party and other groups advocating for black militarism is often seen today as an unwelcome injection of radicalism into a movement founded on something akin to Gandhi’s principles of nonviolent resistance.

In this book, however, Cobb shows that this narrative is overwhelmingly false. There was a longstanding tradition of armed resistance within the black community before the 1960s. The nonviolence of the civil rights movement turns out to be inseparable from the use of guns as self-defense.

Through impressive historical scholarship—focused primarily on the memories of community organizers who entered southern communities as outsiders—Cobb crafts a compelling, convincing case that, in the struggle to attain civil rights, guns were often as integral as gospel songs, even if the latter captured the popular imagination more effectively.

The first few chapters of Cobb’s book are a history lesson, tracing the path of black militancy in the United States. Cobb emphasizes the persistent fear of armed black insurrection among white leaders and politicians, including the especially fascinating worry that liberated slaves would seek revenge against their former masters. Thomas Jefferson gets a particularly harsh, albeit fair, treatment. Cobb correctly points out the cruel irony of the author of the Declaration of Independence asking John Adams, “Are our slaves to be presented with freedom and a dagger?”

Additionally, Cobb attributes much of early black militancy across centuries—by which he means organized, armed resistance to white supremacy—to war and its aftermath. War was an opportunity for black soldiers to show that racist misconceptions about them (their ability, their loyalty) were unfounded. Black veterans returning home often had a renewed sense of the importance of democratic ideals. Tragically, though, early attempts at black armed resistance were often met by disproportionately vicious levels of white terrorism, the vengeful flipside of Jefferson’s more benign worry.

The failure of Reconstruction was not simply an inability to implement more egalitarian public policy, but rather a direct result of “a decade of savage campaigns of violence carried out both by local governments…and by vigilante terrorists.” In this environment, armed resistance was not a method of acquiring liberty, but rather a necessary tactic for survival.

Most black leaders argued, however, that a move towards greater freedom would, to quote Frederick Douglass, require the use of “the ballot box, the jury box, and the cartridge box.” Then, too, World War I and II—the latter especially, with its idealistic fight against the fascism of the Axis powers—provoked a newfound thirst for freedom among black veterans returning home. This desire was especially acute among this particular group, as many veterans grew up during or immediately after a time historians often refer to as “the nadir” of race relations in America. An era that began around 1877, with the failure of Reconstruction, and lasted well into the 20th century, it was characterized by widespread attempts to disenfranchise black people, which often manifested through the twin forces of institutional discrimination and white terrorism.

Black veterans returning home refused to accept the system of white supremacy that had controlled the entirety of their lives up to that point, and Cobb marks the decision by groups of armed black veterans to assert their right to self-defense as the moment “where the modern civil rights movement truly begins.”

Though the historical background is a horrifically fascinating and worthwhile read, the book’s excellence truly emerges when Cobb begins to explore the civil rights movements of the 1960s, and the attendant tension between the armed, local black citizens of the deep South and educated, genteel organizers of the civil rights groups initially committed to nonviolence, such as the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE). The overall thesis of his book that arises out of this tension—that the concept of nonviolent resistance was inextricably linked to a much older tradition of armed resistance—is well supported, with reams of personal interviews and incisive analysis of the campaigns of terror many white southerners waged against black activists, and the various ways in which these activists responded.

Cobb recounts one illustrative example, writing on how Margaret Block, an organizer with the SNCC, was asked by her host, eighty-six-year-old Janie Brewer, what the SNCC stood for. Block recounts Brewer’s reaction to the acronym: “And she stopped me. [She said,] ‘You said nonviolent. If somebody come at you, you ain’t gonna do nothing.’…She pulled up a big ole rifle…She kept a big rifle behind the chair… ‘Shit, we ain’t nonviolent.’ ”

Activists from these groups were acutely aware that they were coming into a region ravaged by years of a particular, violent kind of white supremacy, and that it would be futile and counterproductive to pry the guns away from the hands of those who had needed them for so long. Brewer’s remark is also prophetic in another way: assassination and, less fatally, intimidation attempts were an inescapable reality for many activists, regardless of their origin. The matter-of-fact way in which Cobb devotes a single sentence to the death of Medgar Evers—shot by a hidden gunman in the driveway of his own home—is a tragic example of the commonality of such events.

Even the most ardently nonviolent organizers were reluctant in their efforts to convince locals to lay down their arms. This was partially due to the need to gain respect and local support, but locals often also changed how incoming organizers perceived guns. Cobb tells the story of Dave Dennis, an organizer with CORE who, in response to an explanation of the group’s nonviolent philosophy, was simply told: “This is my town and these are my people. I’m here to protect my people and even if you don’t like this I’m not going anywhere. So maybe you better leave.” The only reply Dennis could muster was, “Yes, sir.”

Cobb also briefly tackles the question of how nonviolence came to be seen as the predominant form of civil rights resistance. Even Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., after all, kept guns in his home. According to Cobb, nonviolence gained in popularity after the student sit-ins against segregation that began in a North Carolina Woolworth’ss: “The quiet dignity of well-dressed students who sat in or picketed, not retaliating even while being attacked, won sympathy for the civil rights movement and inspired other student activists to follow their lead.” The imagery and message of nonviolence was, it seems, inherently appealing; King’s oratory touched a broader base than Janice Brewer’s brusqueness.

At the end of his epilogue, Cobb writes: “But there was a time when people on both sides of America’s racial divide embraced their right to self-protection, and when rights were won because of it. We would do well to remember that fact today.” This is the first time he comes close to making anything like a normative appeal to the reader. The murkiness of his injunction, though, is slightly worrying. Is this simply an exhortation to the reader to forgo the all-too-common mythologizing of the civil rights movement for a clearer view of the past? Or is it instead asking today’s activists to adopt the principles and practices of armed resistance groups? Cobb’s intention in illuminating the forgotten past of the civil rights movement is clearly not completely apolitical but one is left wishing he had devoted a chapter or two to explore the implications of his work, especially after the ending seems so tantalizingly unfinished.

Cobb was himself a field secretary with the SNCC, though he admits in the afterword that he “never subscribed to nonviolence as a way of life.” Regardless, the book, while at times personal is not memoir. With a few minor exceptions, Cobb keeps the tone descriptive, which only works to emphasize the breadth and depth of his research. That is not to say that this is a dry, academic work. Cobb has a tendency to anchor his chapters using vivid, bloody stories of black resistance, and the evenness of his tone only serves to highlight the grotesque nature of his material.

Nevertheless, the centerpiece of the book, and the reason it works so well, is its vast, convincing array of historical evidence. This is full-blooded revisionism—at least as applied to popular ideas about the civil rights movement—and Cobb rises to the challenge brilliantly. With this particular work of historical journalism, Cobb has produced a valuable corrective to misconceptions about civil rights, restoring a sense of balance to the historical record.

Charles, Cobb Jr. This Nonviolent Stuff’ll Get You Killed. Basic Books. 320 pages.