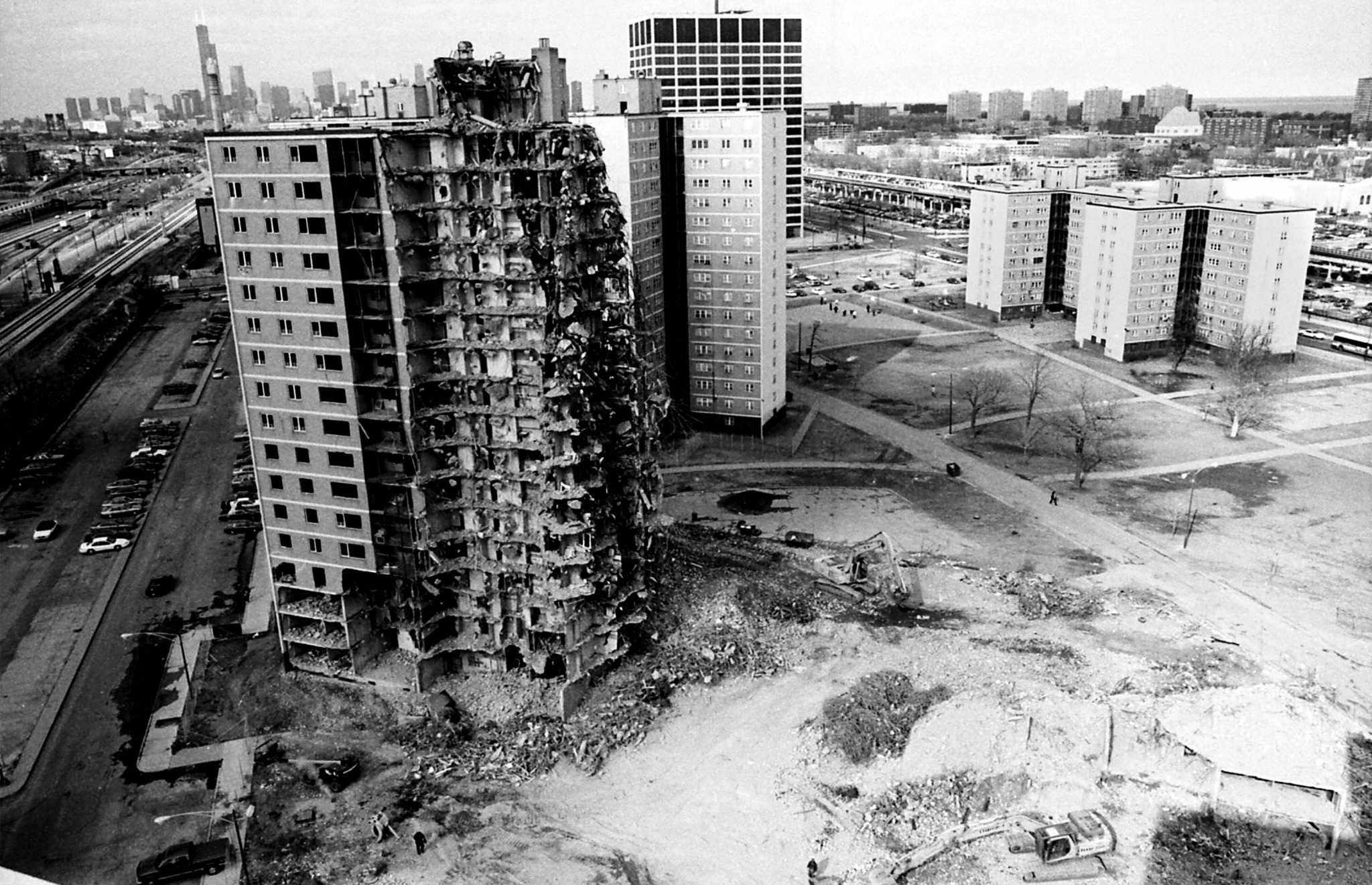

The world that journalist and activist Jamie Kalven depicted nearly a decade ago in the monumental series on police abuse “Kicking the Pigeon” has largely disappeared. The housing projects at Stateway Gardens, where a clique of Chicago Police Department officers known to many residents as the “skullcap gang” sexually assaulted and tormented Diane Bond, the central figure of the series, along with others, were torn down in 2007. But, as documented through the work of activists and organizations featured throughout this issue, the kinds of concerns about police accountability raised by Kalven’s journalism remain highly relevant.

It was out of respect for those concerns that the Illinois Appellate Court ruled this past March that the public has the right to access documents and information pertaining to police misconduct allegations. That ruling was the result of seven years of legal work done by Jamie Kalven and the University of Chicago Law School’s Craig Futterman. In 2007, Kalven asked the district court to make public confidential documents identifying CPD officers with a significant number of complaints made against them, including those accused in the Bond case. After District Judge Joan Lefkow granted Kalven’s request, the city appealed, leading to the overturning of Lekow’s ruling by the 7th Court of Appeals in 2009. Kalven and his team appealed that second ruling, leading to this spring’s victory. In June, the Emanuel administration announced that it would not appeal the new ruling, and instead outlined unprecedented new procedures that will allow the public to access investigative documents relating to police misconduct.

The following is an edited and condensed version of “Kicking the Pigeon,” the series that produced the allegations that led to Kalven’s suit against the city. It was originally published in 2005 on The View from The Ground, an online publication of the Invisible Institute, a journalistic collective comprised of Kalven and five other members, that publishes investigative journalism about marginalized issues and communities. The data and statistics referenced in the piece were accurate at the time of original publication. The Office of Professional Standards (OPS), referenced throughout the piece, was replaced by the Independent Police Review Authority (IPRA) in 2007. Although IPRA, unlike the OPS, is an independent office outside of the CPD, the Chicago Justice Project, a nonprofit advocacy group focused on issues of police accountability, alleges that the office has not significantly improved on the former organization’s rate of sustaining complaints against officers. (Osita Nwanevu)

Content warning: This piece contains graphic descriptions of sexual assault and violence.

On Sunday, April 13, 2003, at about 5pm, Diane Bond, a forty-eight-year-old mother of three, stepped out of her eighth-floor apartment in 3651 S. Federal, the last remaining highrise at the Stateway Gardens public housing development, and encountered three white men. Although not in uniform, they were immediately recognizable by their postures, body language, and bulletproof vests as police officers. Bond gave me the following account of what happened next.

“Where do you live at?” one of the officers asked. He had a round face and closely cropped hair. Bond later identified him as Christ Savickas.

“Right there,” she pointed to her door.

He put his gun to her right temple and snatched her keys from her hand.

Keeping his gun pressed to Bond’s head, he opened her front door and forced her into her home. The other officers followed. As Bond stood looking on, they began throwing her belongings around. When she protested, one of them handcuffed her wrists behind her back and ordered her to sit on the floor in the hallway of the two-bedroom apartment.

An officer with salt-and-pepper hair, whom Bond later identified as Robert Stegmiller, entered the apartment with a middle-aged man in handcuffs and called out to his partners, “We’ve got another one.”

Bond’s nineteen-year-old son Willie Murphy and a friend, Demetrius Miller, were playing video games in his bedroom at the back of the apartment. Two officers entered the room with their guns drawn. They ordered the boys to lie face down on the floor, kicked them, handcuffed them, then stood them up and hit them a few times.

“Why are you all doing this?” Bond protested.

Savickas came into the hall and yelled at her, “Shut up, cunt.” He slapped her across the face, then kicked her in the ribs.

In the course of searching the apartment, the officers threw Bond’s belongings on the floor, breaking her drinking glasses. Savickas knocked to the floor a large picture of a brown-skinned Jesus that sits atop a standing lamp in a corner of the living room.

“Would you pick up my Jesus picture?” Bond appealed to him.

“Fuck Jesus,” replied Christ Savickas, “and you too, you cunt bitch.”

Stegmiller then forced Bond to her feet, led her into her bedroom, and closed the door.

“Give us something to go on,” he told her. “If you don’t, we’ll put two bags on you.” He took off his bulletproof vest and laid it on the windowsill. He removed the handcuffs from her wrists.

“Look into my eyes, and tell me where the drugs are. If you do,” he gestured toward the hallway where the man he had brought into the apartment was being held, “only that fat motherfucker will go to jail.”

Another officer entered the bedroom. Bond later identified him as Edwin Utreras. “Has she been searched?” he asked. “I’m not waiting on no female.”

Utreras took her into the bathroom and closed the door. He ordered her to unfasten her bra and shake it up and down. Sobbing, she did as he told her. He ordered her to take her shoes off. Then he told her to pull her pants down and stick her hand inside her panties. Standing inches away in the small bathroom, he made her repeatedly pull her panties away from her body, exposing herself, while he looked on.

“You’ve got three seconds to tell me where they hide it or you’re going to jail.” She extended her arms, wrists together, for him to handcuff her and take her to jail.

Utreras didn’t handcuff her. He returned her to the hall and ordered her to sit on the floor. An officer she later identified as Andrew Schoeff was beating the middle-aged man Stegmiller had earlier brought into the apartment. Bond and the boys looked on as he repeatedly punched the man in the face.

“He was beating hard on him,” recalled Demetrius Miller. “Full force.”

Knocked off balance by his blows, the man fell on a framed picture of the Last Supper that was resting on the sofa. The glass shattered.

“There ain’t nothing in this house,” Bond kept insisting. “There ain’t nothing in this house.”

“Give us the shit, and we’ll put it on him,” said Stegmiller.

The name of the man to whom he referred, the man his colleague was beating, is Mike Fuller. On Fuller’s account, he had been descending from a friend’s apartment on the sixteenth floor when he encountered Stegmiller coming up the stairs between the fifth and sixth floors.

“Where are you coming from?” Stegmiller demanded.

“From the sixteenth floor,” he replied.

“You’re lying,” said Stegmiller. “You’re coming from the eighth floor.”

He grabbed Fuller and searched him. Finding $100, Stegmiller pocketed it, then pushed him up the stairs. “I wouldn’t mind shooting me a motherfucker,” he said, “if you try to run.”

Stegmiller took Fuller to Bond’s apartment. “He kept telling me that’s where I’d run to,” said Fuller. Once inside the apartment, Stegmiller took a flashlight from a shelf in the kitchen and beat the handcuffed Fuller on the head with it. (“They don’t beat you,” he observed, “till after they cuff you.”) “If I find dope,” Stegmiller threatened, “it’s gonna be yours.”

“I saw how they ramshackled her house,” Fuller recalled.

The officers, having found no drugs, were now drifting out of the apartment. Stegmiller made a proposition to the two boys: if they beat up Fuller, they could go free. “If you don’t beat his ass,” he told Murphy, “we’ll take you and your mother to jail.”

The boys put on a show for the officers. (“Hitting him on the arms, fake kicking,” Miller said later. “No head shots.”) After they threw a few punches, Stegmiller intervened and removed Fuller’s handcuffs “to make it a fair fight.” The three rolled around on the floor for a couple of minutes. The officers looked on and laughed.

“I told the boys to make it look good,” Fuller recalled. “It was for their amusement.”

Stegmiller applauded. He left laughing. No arrests were made.

The basis for this narrative is a series of interviews with Diane Bond, beginning on the day after the alleged incident, April 14, 2003, and continuing to the present; interviews with Willie Murphy, Demetrius Miller, and Michael Fuller; and the plaintiff’s statement of facts in Bond v. Chicago Police Officers Utreras, et al, a federal civil rights suit brought by Ms. Bond.

Officers Robert Stegmiller, Christ Savickas, Andrew Schoeff, and Edwin Utreras deny having any contact with Ms. Bond on the dates alleged.

“It’s like a nightmare,” Bond told me the day after her encounter with the police. “All I did last night was cry.”

When I knocked on her door, she was cleaning up. She gave me a tour and showed me the damage—the shattered picture of the Last Supper, the damaged frame of Murphy’s high school graduation picture, the broken drinking glasses, the clothes and objects strewn around Murphy’s room, the one room she had not yet cleaned up.

I had at that time known Diane Bond for several years. In my role as advisor to the Stateway Gardens resident council, I worked out of an office on the ground floor of 3544 S. State, the building in which she lived. Every so often I would see her in passing, most often going to or coming from her job as a public school janitor. I didn’t know her well but formed an impression of a cheerful woman in coveralls who moved through the turbulent scene “up under the building”—at once drug marketplace and village square—with an easygoing, friendly manner.

Her apartment in 3651 S. Federal is deeply inhabited. Two large, comfortable sofas, arranged around a coffee table, dominate the living room. The top of the television cabinet functions as a sort of household altar for religious objects and family photos, among them pictures of her three sons: Delfonzo, now thirty years old, Larry, twenty-nine, and Willie, twenty-one. Working as a janitor, Bond raised her boys as a single mother. She expresses pride in the fact that they have largely managed to stay clear of trouble in an environment where that is no small achievement. For the last three years, she has been involved with a man named Billie Johnson. Quiet and gentle in manner, Johnson labors in the economy of hustle: repairing cars, helping maintain the Stateway Park District field house and grounds, doing odd jobs for his neighbors.

At my urging, Bond went to the Office of Professional Standards of the Chicago Police Department to register a complaint against the officers who she said had assaulted her. As it happens, the OPS office is located at 35th and State in the IIT Research Institute Tower, the nineteen-story building visible from her apartment that stands like a wall of glass and steel between Stateway and the IIT campus to the north.

OPS investigates complaints of excessive force by the police. It is staffed by civilians and headed by a chief administrator who reports to the superintendent of police. When someone makes a complaint to OPS, an investigator takes down his or her statement of what happened. The individual is asked to review the statement and to sign it. In theory, OPS conducts its own investigation, interviewing the police officer or officers involved along with any witnesses, then renders a judgment. In the vast majority of cases, it finds that the complaint is “not sustained”—i.e., the investigators could not determine the validity of the allegations of abuse. In a small number of cases each year, OPS sustains the complaint and recommends discipline for the officer(s) involved. An officer facing discipline may appeal to the Police Board, a body composed of nine civilians appointed by the mayor. The board has the power to reduce the punishment recommended by OPS or the superintendent and to reverse OPS altogether.

OPS has long been sharply criticized by human rights activists who argue that it functions not as a vehicle for holding the police accountable but as a shield against such accountability. They cite the numbers. For example, from 2001 through 2003, OPS received at least 7,610 complaints of police brutality. Significant discipline was imposed by the CPD in only thirteen of those cases—six officers were terminated and seven were suspended for thirty days or more. In other words, an officer charged with brutality during 2001–2003 had less than a one-in-a-thousand chance of being fired.

It is, thus, extremely unlikely that an OPS investigation will yield any meaningful discipline for the officers involved. Yet it does not seem unreasonable to hope that a pending OPS investigation will at least serve to deter the officers named from further contact with the person who filed the complaint. That, at any rate, is what I told Diane Bond by way of reassurance.

On the evening of April 28, 2003—two weeks after she filed a complaint with OPS about the April 13 incident—Diane Bond returned home at about 7:30pm from the corner store. She encountered Officers Stegmiller, Savickas, Utreras, and Schoeff outside her apartment door. Also present was a fifth officer she later identified as Joseph Seinitz. He was tall and lean, in his thirties, with closely cropped blond hair. She recognized him as the officer known on the street as “Macintosh.”

The officers had two young men in custody. Demetrius Miller was one of them; she didn’t recognize the other. His name, she gathered, was Robert Travis. Bond recounted the incident to me the next day.

One of the officers barked at her, “Get the hell out of here!” Moments later, as she was descending the stairs, another yelled, “Come here!” Seinitz came down the stairs and grabbed her. Holding her by the collar of her jacket, he dragged her back up to the eighth floor, her body scraping against the stairs.

While Seinitz held Bond, Savickas punched her in the face and demanded, “Give me your fucking keys!”

“They snatched my jacket off and took the keys out of my pocket,” she told me. “I was so scared, I pissed on myself.”

The officers entered her apartment. They ordered her to sit on the sofa in her living room. The two young men, handcuffed, sat on her glass coffee table.

Stegmiller came in from outside the apartment and placed two bags of drugs on the top of her microwave. He would later testify that he had found the drugs in an “EXIT” sign in the corridor outside her apartment.

One officer stayed with Bond and the two boys, while the other three searched the apartment. The officer leaned back on her television cabinet, where family pictures and religious artifacts were arrayed. She begged him not to sit on her icon of the Virgin Mary.

“Fuck the Virgin Mary,” he said, as he swept his hand across the top of the cabinet, knocking the icon and other religious objects to the floor.

Seinitz and two other officers were searching Bond’s bedroom. They motioned to her to come into the room. They told her to pull down her pants. Then they told her to pull down her panties.

Seinitz brandished a pair of needle-nose locking pliers and threatened to pull out her teeth if she didn’t cooperate.

“Why’d you pee on yourself?” one of them taunted.

They ordered her to bend over with her back to them, exposing herself. While she was in that position, they instructed her to reach inside her vagina “and pull out the drugs.”

Bond was overcome by terror. As a child and young woman, she had, she told me, suffered repeated sexual abuse at the hands of men, including a gang rape when she was a high school student. Now, despite the official complaint she had made against these officers, they were again swarming around her, threatening her, cursing her, forcing her to undress. She feared they would rape or kill her. “I didn’t know what they were going to do next.” She only knew that each thing they did was worse than the last.

They brought her back into the living room. One of the officers instructed Travis to “stiffen up,” as he punched him repeatedly in the stomach.

“Do you want us to put a package on her?” the officer asked Travis.

“I don’t care what you do with her,” he replied.

They left with the two men.

Bond locked the door, collapsed on her sofa, and wept.

Being forced to expose herself while Officer Seinitz and the others threatened her was “like a dry rape,” she told me the day after the incident.

On April 30, 2003—two days after her second encounter with the police—Bond and her boyfriend Billie Johnson went downstairs at about 11:30pm. They were going to the store to get some wine. As they came out of the stairwell into the elevator corridor in the lobby, they encountered Officers Stegmiller and Savickas. Stegmiller grabbed Bond by the arm.

“Where are you going?” he demanded.

“To the store.”

She had her keys in her hand.

“Give me your keys,” he said. “Give me your goddamn keys.”

“I’m not going to give you my keys,” she protested. “I’m not going through that again.”

She shifted her keys from one hand to the other and put them in her pocket. Stegmiller grabbed her around the throat and pushed her up against the elevator door.

“I’ll beat your motherfucking ass.”

“Somebody please help me,” she called out. “Please help me.”

Savickas stood by, while Stegmiller choked Bond. When Johnson appealed to him to intervene, Savickas gave him a hard push in the chest.

Only when other residents came on the scene did Stegmiller release Bond and tell her, “Get the fuck out of here.”

“I was crying, I was angry. I was hysterical,” Bond recalled. “I told my old man, ‘I’m so tired. I’m tired of this.”

She and Johnson went directly to the OPS in the IIT building at 35th and State. Although OPS is open twenty-four hours a day, security personnel in the lobby of the building would not let her go up to the office. She left and went to the administrative headquarters of the CPD at 35th and Michigan. The officers at the desk were not welcoming. They threatened to put Bond and Johnson in lockup. In the end, they took down her name and address. She then went to a store on the corner of 37th and State and attempted to call OPS, but the phone in the store was dead.

It was raining hard. Bond and Johnson returned to the building. The police were still there. They slipped in. He went to her apartment on the eighth floor. She went upstairs to thank the neighbors whose presence had stopped Stegmiller’s assault on her. In a vacant apartment on the fifteenth floor, she saw Seinitz—“Macintosh.” He didn’t see her. She fled the building. Again, she attempted to go to OPS, and again she was barred by security. She returned to 3651-53 S. Federal and waited outside in the rain and darkness for about half an hour until the police left the building. Then she climbed the stairs to her home.

Officers Seinitz, Savickas, Stegmiller, Utreras, and Schoeff were, until recently, familiar presences at Stateway Gardens and other South Side public housing developments. With the exception of Seinitz, who is known as “Macintosh,” they are referred to on the street not by their names but as “the skullcap crew” (they often wear watch caps) or “the skinhead crew” (several have buzz cuts). They are reputed to prey on the drug trade—routinely extorting money, drugs, and guns from drug dealers—in the guise of combating it. But what distinguishes them, above all, say residents, is their racism. Several are rumored to have swastika tattoos on their bodies. One resident described them to me as “KKK under blue-and-white.” And black officers have been heard to refer to them as “that Aryan crew.” “They get their jollies humiliating black folks,” a former Stateway resident told me. “They get off on it.”

A question persists at the center of this narrative. Why? Assuming Diane Bond’s account is true, why did members of the skullcap crew repeatedly invade her home and her body? What possible rationale could there be for their conduct? The abuses occurred in the context of the “war on drugs.” That was the pretext for raiding her building, searching her home and person, and interrogating her. But does the enforcement of drug laws, in the absence of individualized suspicion (much less a search warrant supported by probable cause), explain the abuses? Does it make sense of the senseless, sadistic conduct alleged? This is not an easy question to answer. For it demands we entertain the possibility that the abuses were an end in themselves and the drug war a vehicle to that end: the possibility that members of the CPD terrorized Diane Bond for the perverse pleasure of it.

I recall arriving at 3651 S. Federal on a winter day in 2003, just as an unmarked police car was driving away. Once it was out of sight, the drug marketplace up under the building would reopen for business. Several people were standing outside the building, looking on. Among them was a woman known on the street as Betty Boop, who acts as a lookout for drug dealers to support her heroin addiction.

“You know what that crazy man did?” she asked me, referring to one of the officers. “He just walked up and kicked that bird for no reason.”

She pointed to a pigeon on the pavement. It was wobbly and disoriented—in obvious distress.

“Now why did he have to do that?” Betty asked.

The image comes back to me now, as I try to make sense of the patterns of the skullcap crew: kicking the pigeon. Casual cruelty can become a way of life in a setting where everything is permitted, where you enjoy de facto dominion over other human beings who are by definition not to be believed. Any account they might give as victims or witnesses is impeached in advance, for they are gangbangers and drug dealers. They are the mothers and grandmothers of gangbangers and drug dealers. They are residents of a public housing development that is seen less as a community than as a loose criminal conspiracy to engage in gangbanging and drug dealing. Some officers are made uncomfortable by the license this perverse logic confers upon them; they know if they don’t restrain themselves, nobody else will. And some exult in the power it gives them to toy with other human beings.

Seen in this light, it was not something threatening about Diane Bond that drew the skullcap crew to her. It was something vulnerable.

On April 12, 2004, the Edwin F. Mandel Legal Aid Clinic of the University of Chicago Law School filed a federal civil rights suit on behalf of Diane Bond. The suit names as defendants five officers—Edwin Utreras, Andrew Schoeff, Christ Savickas, Robert Stegmiller, and Joseph Seinitz—and the city of Chicago. It claims the defendants violated Bond’s constitutional rights by subjecting her to illegal searches, unlawful seizures, and the use of excessive force. It further claims they were motivated to abuse Bond by her gender and race, in violation of the equal protection provisions of the Fourteenth Amendment and the Illinois Hate Crime Statute.

The Bond suit is the fifth federal civil rights suit that Professor Craig Futterman and his student colleagues at the Mandel Clinic have brought against the CPD in recent years as part of an initiative called the Stateway Civil Rights Project. In my role as advisor to the Stateway Gardens resident council, I helped develop this initiative and initially brought the Bond incidents to the attention of the UofC lawyers.

On April 7, 2005, Futterman filed a motion for permission to amend the complaint to charge that Bond’s abuse resulted from systemic practices and policies of the CPD, and to add as defendants Philip Cline, the superintendent of police, Terry Hillard, the former superintendent, and Lori Lightfoot, the former administrator of the OPS. On June 6, the court granted the motion.

The theory of the amended complaint is that the city had a de facto policy of “failing to properly supervise, monitor, discipline, counsel, and otherwise control its police officers,” and that top police officials were aware “these practices would result in preventable police abuse.” As a result, Futterman argues, members of the skullcap crew knew they could act with impunity. The city and the high officials named in the suit were thus complicit in their abuses.

The city’s defense strategy in Diane Bond v. Chicago Police Officers Edwin Utreras, et al is straightforward: each officer denies having had any contact with Diane Bond on any of the dates she claims she was abused. In their reply brief to a motion seeking access to police photos for the purpose of identification, the city attorneys make reference to “the highly unusual and outlandish allegations of abuse in this case” and to “the vague and reckless nature of plaintiff accusations”—language that suggests they will seek to portray Bond as unstable and delusional, that they will argue the abuses she alleges are figments of her imagination.

The fact she was not arrested is relevant to the issue being addressed in the brief—access to police photos—for the absence of the documentation provided by arrest reports makes identification of the officers involved a central issue. The brief’s phrasing and repetition, however, go beyond that point to imply Bond cannot have been “severely victimized and humiliated by the police officers,” because she was not arrested in any of the incidents.

The second means by which the city attorneys seek to impeach Bond’s account is to emphasize repeatedly that her physical injuries are inconsistent with her allegations of abuse. For example, with respect to the first incident, they state:

Despite the elaborate description of physical abuse she gave, as of April 15, 2003, plaintiff had only a dime size area of swelling under her right eye for which she sought no medical treatment.

The city seeks, in effect, to narrow “abuse” to “physical abuse.” In her OPS interview regarding the April 13 incident, Bond states she was slapped once in the face and kicked once in the side. One sentence of the two-and-a-half page interview is devoted to this physical abuse. The “elaborate description” of abuses that constitutes the bulk of the interview details a series of assaults that caused serious injury without leaving marks on her body.

She describes, among other things, having an officer put a gun to her head; witnessing officers destroying her property, including religious objects sacred to her; looking on while officers struck her teenaged son; being forced to disrobe and expose herself under the gaze of a male officer; watching the police beat a man they had brought into her home; and seeing her son and his friend forced to assault that man—to put on a demeaning show for the amusement of the officers—as a condition of release. The injuries inflicted by these abuses were not the kind that could be documented by a trip to the emergency room.

OPS has an inherently difficult mission. Police misconduct tends to take place in the shadows. And the darkness is deepened by the “code of silence” among officers. The Bond complaint describes the code:

According to standard practice, police officers refuse to report instances of police misconduct, despite their obligation under police regulations to do so. Police officers either remain silent or give false and misleading information during official investigations in order to protect themselves and fellow officers from internal discipline, civil liability, and criminal charges.

In order to bring misconduct to light, the CPD would need to move aggressively against this institutional culture. It would need to bring a high degree of skepticism to the process and be alert to the gang phenomenon that so often figures in police misconduct. It would need to create incentives and disincentives to encourage cooperation. And it would need to provide meaningful forms of protection for officers who come forward to report on the misconduct of fellow officers.

The CPD does none of these things. OPS uncritically gives corroborative weight to the statements of other officers at the scene. It appears rarely, if ever, to recommend that an officer who witnessed an incident of misconduct by a fellow officer be charged with failure to report a crime. And it is subject to a city policy that bars the CPD from transferring whistleblowers from their units in order to protect them against retaliation. Rather than penetrating the code of silence, OPS practices mesh with it to form a system that seems designed to produce judgments of “not sustained.”

The universal defense offered by police departments charged with brutality, as by governments charged with torture, is that “there will always be a few bad apples in any barrel.” There is a measure of truth in this. It is generally agreed that the vast preponderance of abuse is committed by perhaps five percent of officers. This is not an insignificant number in a force of more than 13,000. And there is no reason to assume the five percent is evenly distributed; there may be sections of the police force, such as the public housing section, where the percentage is significantly higher.

Yet the image of “a few bad apples” remains plausible. It is a way of talking about police abuse that keeps visible the large majority of officers who do not commit abuses and can be assumed to deplore such conduct. The image is, however, fatally flawed in two respects. It does not comprehend the scale of the harm a handful of violent agents, acting with impunity, can do. Nor does it convey the impact those few bad apples, if not removed, will have on the barrel.

“We’re the real police.” Several Stateway residents have quoted this declaration by members of the skullcap crew. Also: “You know what we’re capable of.” Or alternatively: “You have no idea what we’re capable of.” The implication is clear: we are above the law. Residents have little reason to question that assertion, for despite numerous complaints against them, crew members have continued to prey at will on public housing communities.

A rogue crew, operating with impunity, can also do profound, long-lasting damage to the legitimacy of government, alienating whole populations from civil authority and engendering the criminal and anti-social behaviors it is supposedly combating. This is a dynamic I have become familiar with during my years at Stateway.

As you read this account of the abuses Diane Bond alleges Chicago police officers committed against her—so raw, so appalling, so unacceptable—did you find yourself thinking, “But maybe she’s a drug dealer…maybe someone close to her, her son perhaps or her boyfriend, is a drug dealer…maybe her community is overrun by drug dealers”? Did you find yourself searching for reasons that could somehow explain and perhaps justify the police conduct alleged?

The impulse is understandable. Indeed, it is hard to resist, because we do not want to believe police officers would act this way. But consider the implications. Are “the series of horrendous acts” (to quote the city attorneys) alleged in the Bond case any less horrendous, if the officers had probable cause to come to her door? The defendants are not making that argument. They are flatly denying any contact whatsoever with Bond on the dates of the alleged incidents. Yet is there perhaps a sense in which we are inclined to make the argument on their behalf? Are we so conditioned to apartheid justice—to “the war on drugs” as an exception to constitutional norms akin to the exception being carved out for “the war on terror”—that we can no longer confidently recognize the heinous nature of the crimes at issue?

After decades of mass incarceration and the practice of guilt by association have we so lost our bearings that the mantra “gangs and drugs” suffices as an all-purpose rationale for any act a police officer commits in an abandoned neighborhood? Has the process by which those who live in such neighborhoods come to be defined as “criminals” rather than “blacks” (or “fellow citizens” or “neighbors”) advanced so far that it now blinds us to the character and antecedents of what we are allowing to be done in our names?

Postscript: In 2007, Bond settled her case with the city out of court for $150,000.

© 2014 the Invisible Institute, all rights reserved.

Wow.