Jahmal Cole has been a public speaker since 1988. He was four during his first speech. That address, delivered to his fellow preschool graduates and their families, now serves as the mission statement for his life, a narrative founded on community building and positivity.

“I always knew I’d be a speaker,” he says. “But when I started giving presentations, I realized that I actually learn more from community members than what I was telling them, so I better start learning, I better start listening,” Cole said.

Twenty-six years later, Cole heads the Role Model Movement (RMM), a nonprofit that aims to resolve one of Chicago’s central contradictions—the city’s tendency to accept and celebrate its diverse but racially and socioeconomically segregated neighborhoods.

Cole began to see this tension while volunteering at the Cook County Juvenile Detention Center in 2008. Assigned to the AT, or automatic transfer unit, Cole worked primarily with teenagers who would be transferred to an Illinois prison for ten-fifteen year sentences due to the nature of their crimes.

“I was a little bit nervous, but when they walked into the room I realized that they weren’t sociopaths like Chicago media makes them out to be,” says Cole. “They were actually the same guys I see on the Red Line. They could’ve been anything they wanted to be, but they just never had positive role models.”

For Cole, one of the most positive role models available to these teenagers lies in the city itself. Chicago’s abundance of diversity in culture and life experiences can provide the impetus necessary for young people to see beyond their circumstances. However, in conversations with the inmates, it became clear that the city of Chicago existed as a stereotype for them in the same way that their own lives were reduced to a few headlines in the Tribune.

When he asked them whether they had ever seen downtown Chicago, a chorus of no’s would reverberate from the walls of the detention center. Most would instead talk about their own neighborhoods, oblivious to the rest of the city. Cole was struck by the way that these teenagers described their homes, in terms of only a few streets or even a single block.

“I found it ironic that they could see downtown from their block or their hood, but had never seen it for themselves,” Cole said.

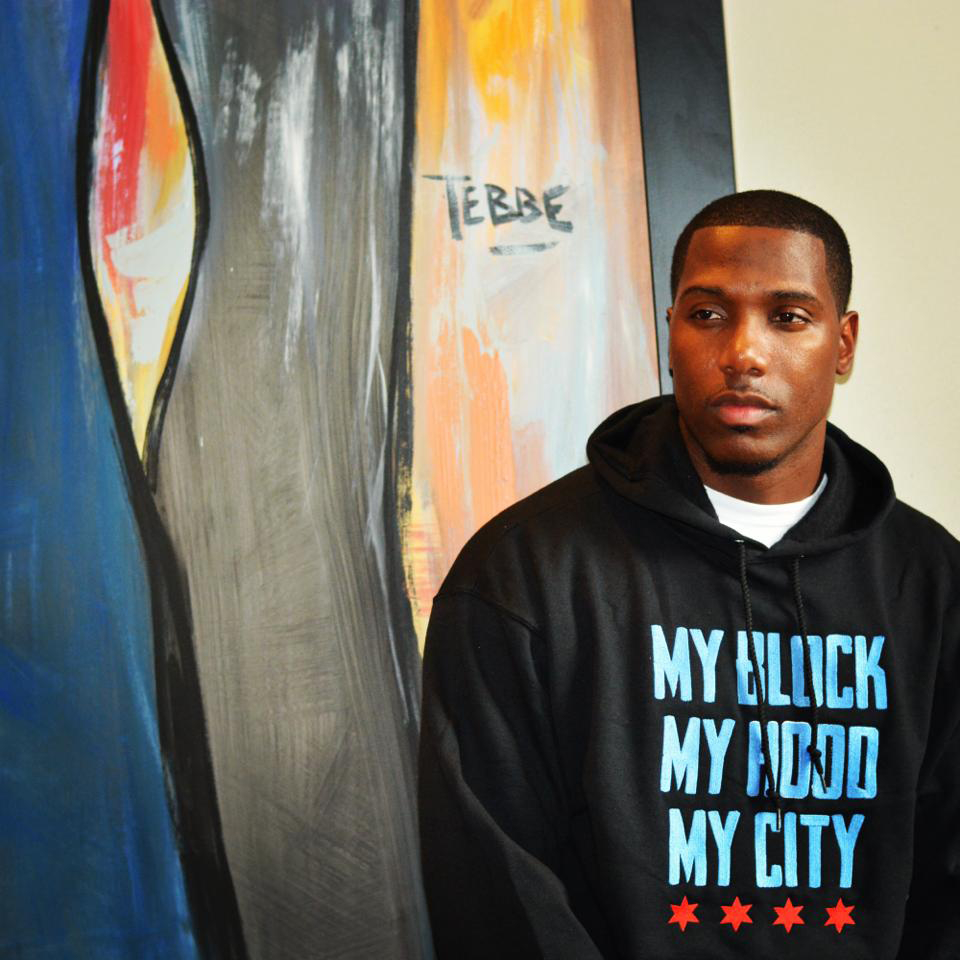

My Block, My Hood, My City (M3) is Cole’s answer to this lack of perspective. “At the beginning I called it ‘Changing Perspectives’ but that didn’t look good on t-shirts, so I was stumped when I was creating my Kickstarter,” he explains. ”And a mentor of mine said, ‘Come on, you’re always talking about my block, my hood, my city—why don’t you just put that on a t-shirt?’ So that’s how it was born,” Cole explained.

The Explorer’s Club, one of the M3 initiatives, serves as an organized shuttle service for kids from underserved communities to visit neighborhoods, primarily on the North Side, where many have never been and may never have expected to experience. In one instance, Cole accompanied a teenager named Emmanuel from Humboldt Park to a new 3D printing facility in Edgewater. Emmanuel was able to create a 3D printed model of his dream home with the help of the Edgewater Workbench staff and a free online modeling program.

Cole is also working to create a web series under the M3 name which will detail each of Chicago’s seventy-seven community areas in eight-to-ten minute videos starring Cole himself. Each snapshot includes excursions to local establishments, as well as interviews with local residents. The videos provide information on the history of each neighborhood, as well as the role each neighborhood fills within the larger Chicago landscape. These histories include positive segments focused on new businesses, like a profile of the Penthouse Boutique in the Woodlawn episode. They also reflect candidly on some of the problems facing each particular neighborhood, and each community’s efforts to find solutions—in the Rogers Park episode, for instance, Cole speaks with a former gang member. To date, Cole has profiled nine neighborhoods, and he plans on compiling the entire seventy-seven episode series into a documentary.

Cole remedied his own struggles as a young man through travel. A student at an alternative high school, he first doubted the possibility of college enrollment. Two weeks before graduation, after declaring to his high school guidance counselor his plans to enroll at the University of Michigan on an unrealized basketball scholarship, he received a rude awakening.

“She was like, ‘You go to an alternative high school, one, you hardly ever show up in school, two. You better go to the military.’” Cole laughs. “So I ended up ripping a page off a book on her shelf and shoving it in my pocket—she had left for the phone—and with the paper in my pocket, I pulled it out of my pocket, opened it up when I was downstairs and it said ‘Wayne State College, Nebraska.’”

Cole eventually attended Wayne State, where he earned a degree in communications, and took opportunities to travel to Hawaii and the United Kingdom. Cole continued his education with a masters in internet marketing at Full Sail. However, he insists that the most valuable arena for an activist like himself lies in the community itself.

“The communities are my classrooms,” he says. “That’s my education. I was gonna go to law school a year ago, but I decided to travel with M3 and educate myself that way.”

Cole is well known for his community activism, especially among South Side organizations (he lives in Chatham). Asiaha Butler, the co-founder and president of the Residents Association of Englewood (RAGE), counts him among a core group of young visionaries who currently supply their neighborhoods with potential for social growth and welfare, and has hinted at the possibility of collaborations between RAGE and RMM.

Collaborations, but not partnerships—Cole currently wishes to run his nonprofit and its initiatives like the Boy and Girl Scouts of America. The RMM and, more importantly, the M3 names exist separately from any Chicago entity that may be interested in the organization’s goals and strategies. To Cole, RMM is self-sustaining as a brand.

“I think that—I’m open to collaboration, don’t get me wrong—if Chicago Public Schools calls me up and says that they want to implement my program, then I’m all about that,” he says. “But right now, we’re identifying organizations that serve teenagers and providing this experience to them free of charge.”

Much of Cole’s time is spent researching and applying for grants. Both the Explorer’s Club and the 3M web series are expensive, and Cole relies on his own personal funds as well as donations and grants to carry out each trip.

“For every one that I win, I might fail three,” he says of grant applications. “It’s hurtful to fill out a big grant application and wait six months just to find out you lost. That hurts your ego man, you know?”

As a result, Cole is defensive of his own project, and frustrated with Chicago’s climate for nonprofits like his own. Hundreds of NFPs exist within Cook County, and most, if not all, rely on donations and grants in order to complete their work. This creates a level of competition that can be difficult to survive, especially for a business that doesn’t produce any profit of its own.

“You have all these people fighting for the same pool of money, and they are struggling with ideas. And I think I’ve got a fresh idea, I know I do.” said Cole.

The M3 web series has profiled one-seventh of Chicago’s seventy-seven community areas. The Explorer’s Club is also just beginning to kick off, with two completed trips and another planned for a Bulls game trip downtown. Cole hopes to take some sort of statistical analysis from the latter in order to better advertise the program to Chicago organizations that also work to help empower kids from underserved communities.

“In two to three years, I want to see if the Explorer’s Program is working. What are my high school students’ GPAs, are they attending college, what is the college persistence rate. I want to be able to say two years from now that eighty-five percent, ninety-five percent of the Explorers go on to graduate—or go on to enroll in college. And stay in contact, stay engaged,” Cole said.

Cole’s projects are new, and the results of their attempt to combat Chicago’s segregation and its isolation of underprivileged youth will not be seen for a while. Both problems span the entire city. Cole recognizes this and knows that his role in breaking down barriers will be ineffective without support from others—both other organizers and other ordinary Chicagoans.

“People say in Chicago, ‘Do you live in a bad community in Chatham?’ or ‘Is Englewood bad?’ or ‘Is South Shore bad?’ No! Chicago is bad. I mean, we all should take responsibility for what’s going on. So, I think that when somebody gets shot in Englewood—that should actually matter to the people in the Gold Coast, and when that 3D printing company opens up in Edgewater, that should matter to us in Chatham.”