In the early nineties, Jamie Kalven had a crisis of conscience.

“I didn’t want to be the sort of writer that just wrote eloquent essays urging action on other people in response to great social issues,” he recalls.

For Kalven, the solution was to begin spending time in Stateway Gardens, the Chicago Housing Authority high-rise public housing facility that was demolished in 2007. High-rise public housing was a contentious topic in the media at the time, and Kalven hoped to gain a personal perspective on the community so close to his lifelong home in Hyde Park.

“It was several years before I really became aware of consistent patterns of police abuse and police misconduct that weren’t the occasional aberration, but were really daily circumstances,” Kalven recounts.

What Kalven saw led to a question.

“What set of institutional conditions would have to exist for what I’m seeing every day to be the case? I knew it was the case because I was seeing it every day, I was testing it on my nerve endings, I knew it was real. But I didn’t understand what kind of a world it was happening in.”

This question that first crossed Kalven’s mind in Stateway Gardens would eventually lead to the release of the Chicago Police Database on November 10, 2015. The Chicago Police Database, an online tool for public use, presents an unprecedented amount of information about police misconduct, showing the minutest details of 54,581 complaints filed against 8,337 officers. This is the story of how Kalven, through almost a decade of legal battles, turned a question about police accountability into an interactive online tool, and why that matters.

On April 13, 2003, Diane Bond, a resident of the Stateway Gardens public housing development was berated, physically threatened, verbally abused, and forced to expose herself by a group of police officers. This was the first in a series of incidents Kalven recounts in a series of articles eventually collected under the title Kicking the Pigeon.

“I was so embedded in the community, so much a part of the community, that I had sources, knew Ms. Bond, knew enough about the setting and the situation that I believed Ms. Bond,” recalls Kalven. “But because I am not of that community, but move through other spheres, I also had access to lawyers and was able to convince them to take her case.”

Craig Futterman, the lawyer who represented Ms. Bond, had been introduced to Kalven through a mutual friend. Futterman was, and still is, a professor of law at the UofC Law School’s Mandel Legal Aid where he directs the Civil Rights and Police Accountability Project. Collaborating with Kalven, Futterman and his students had worked on a series of federal civil rights cases arising out of incidents at Stateway by the time that Ms. Bond’s case came about.

It was this case, Bond v. Utreras, et al.,that started the series of legal battles that would eventually lead to the release of the information presented in the Chicago Police Database.

In this case, Kalven and his students crafted requests for background information on the five police officers involved in the case. They also requested a list of all officers who had received ten or more complaints in the last five years.

“These requests were really designed to extract information from the city that could be analyzed to see—how does this system work and not work to allow guys that are so outrageously abusive to act with impunity,” said Kalven.

The city granted the request for the documents under a protective order—an agreement that the documents would not be released to the public. Kalven, represented pro bono by Jon Loevy and Samantha Liskow of Loevy & Loevy, intervened as a journalist on behalf of the public. He requested that the protective order be lifted and that the documents be made available to the public at large.

The city granted the request for the documents under a protective order—an agreement that the documents would not be released to the public. Kalven, represented pro bono by Jon Loevy and Samantha Liskow of Loevy & Loevy, intervened as a journalist on behalf of the public. He requested that the protective order be lifted and that the documents be made available to the public at large.

“I don’t think we had high expectations for it succeeding,” Kalven recalls.

In an unexpected turn of events, their request was granted. Judge Joan Lefkow ruled that the documents had “a distinct public character, as it relates to the defendant officers’ performance of their official duties.”

“Without such information,” Lefkow continued, “the public would be unable to supervise the individuals and institutions it has entrusted with the extraordinary authority to arrest and detain persons against their will. With so much at stake, defendants simply cannot be permitted to operate in secrecy.”

The city immediately obtained a stay of her order pending appeal. Two years passed. Ultimately, Judge Lefkow’s decision was overruled. The defeat was disappointing, but one footnote in the ruling left some hope. The passage in question reads: “The protective order does not interfere with Kalven’s ability to try to obtain the documents he seeks directly from the City under the Illinois Freedom of Information Act (FOIA)”

“We took them up on the invitation and drove a truck through that footnote,” Kalven later said in an interview with the Columbia Journalism Review.

Kalven, along with Futterman, Loevy, and Flint Taylor of the People’s Law Office, pushed forward litigation in hopes of making police misconduct investigation files (known as CRs) and lists of officers with repeated complaints (RLs) available to the public.

In March of 2014, Kalven v. City of Chicago was decided in favor of the Kalven camp. The decision reads: “In sum, neither the CRs or RLs are exempt from disclosure under FOIA.”

Under the Illinois Freedom of Information Act, anyone can submit a request for documents from federal agencies that are not currently publicly available. If the description of the requested files is specific enough and the files are not exempt, the agency is obligated to release the documents.

As soon as this decision made the documents publicly available under FOIA, the Tribune and the Sun Times put in requests for all of the disciplinary records of every CPD officer dating back to 1967. Kalven and his cohort made a parallel request for all these records in order to be involved in the litigation.

The City, without litigation, agreed to release all of the information requested.

At that point, the Fraternal Order of Police—Chicago’s police union—filed a lawsuit seeking to bar the city from releasing the information. The union argued that their contract stipulated that disciplinary records be destroyed after five or years depending on the nature of the complaint. A sympathetic judge imposed a temporary injunction.

Currently, the Invisible Institute and the City are working together in this case against the Fraternal Order of Police, arguing for the public release of all of the disciplinary records back to 1967. Oral argument before the Illinois Court of Appeals is expected sometime this fall. Although the Fraternal Order of the Police is objecting to the existence of the older documents, the last four years of complaints of misconduct (from March 2011 to March of 2015) are in Kalven’s possession and will soon be completely available to the public.

By the late nineties, Kalven was deeply embedded in the Stateway Gardens community. Technically squatting, he established an office in a five-bedroom unit on the first floor of one of the high-rises. He served as an advisor to the resident counsel. He ran The Neighborhood Conservation Corps, an employment program of his own creation. In 2001, he started publishing articles online under the title The View from the Ground. The articles were published online, in the early days of web publishing, from his makeshift office on the first floor of a public high rising. As a joke about these makeshift, low-budget circumstances, Kalven included a note that reads “published under the auspices of the Invisible Institute” in one of the early articles. No such Institute existed at the time, but the name stuck. Today, the Invisible Institute is a non-profit with its own office and five employees.

“Over time, the name came to be associated with a set of initiatives and collaborations and public themes. And then lo and behold, it’s become something that resembles an institute—incorporated and funded–that performs a set of research and educational functions.”

The Invisible Institute is a convenient way for Kalven to facilitate the kind of collaborations that he has always been a part of. Craig Futterman was one of Kalven’s first collaborator’s in the realm of police misconduct and is still one of his closest. Chaclyn Hunt, a current members of the Invisible Institute, was introduced to Kalven by Futterman when she was a law student.

After working on legal projects with Kalven and Futterman for two years, Hunt joined the Invisible Institute after graduation. She now directs a program called the Youth/Police Project, an initiative that started out with the goal of teaching teenagers about their rights.

“Our way of going back to the ground, after we made all these big systemic arguments at Stateway, was the idea that we should focus on the simplest atomic particle of these larger phenomena,” Kalven said.

“Which I take to be an encounter between a police officer and a black teenager.”

Hunt quickly found out that teaching a know-your-rights workshop to a class of teenagers that interact with the police on a sometimes daily basis was, in her words, “totally absurd.”

“When you start with [the questions ‘what are your interactions with the police?’ and ‘how do they make you feel?’] and you get into that conversation with kids, and they’re having this grave personal conversation with you, and you say ‘well let me teach you how to deal with that in the future’ they tell you, ‘That’s bullshit! You’re lying, you’re crazy.’”

In its current iteration, the Youth/Police Project is made up of a mixed bag of collaborators–law students and academics, lawyers and journalists–,who meet with a broadcast media class at Hyde Park Academy once a week. Hunt and her team talk to the kids about their encounters with the police, and the kids use their broadcast media skills to record and edit their own interviews and roleplays.

Rajiv Sinclair, an Ottawa native with a background in web development and media production, was visiting a friend in Chicago during the summer of 2014. He met Jamie, saw the work that the Invisible Institute and was engaged in, and never left. Sinclair started out helping the Youth/Police Project with video production, but would soon take on a new role as the technology wizard and web development liaison primarily responsible for the facilitation of the creation of the Chicago Police Database.

“What we’re trying to do going forward is build a lean, agile, small but adequate creative team. That then works in a range of collaborative relationship with others,” describes Kalven. The official Invisible Institute roster also includes two journalists, Darryl Holliday and Alison Flowers, and Audrey Petty, a writer and former professor of English.

Although officially released to the public after the Kalven decision, the complaints of misconduct were a cumbersome collection of scanned government documents. In this form, Kalven’s team assumed that only the most intrepid investigative reporter or academic researcher would engage with the information. The Invisible Institute wanted the data to be readily accessible to anyone and everyone.

“One way to think about this is that the knowledge exists, within the boundaries of a certain set of problems, to fix those problems. But that knowledge is sort of divided from itself and scattered and sort of atomized,” says Kalven. “Part of our challenge is to create the feedback loops, and the sense of possibility that the information you have could actually matter and be acted on. To begin to connect and weave together those different kinds of knowledge.”

“There is a giant disconnect,” adds Hunt, “between people who live every day with police misconduct and the people who have the resources to do something about it.

“Civil rights attorneys, academics, politicians are not living in conditions where there is police misconduct. And it’s difficult for them to access that information. Think about attorneys who are client hunting, who have an idea of what kind of reform they want to see happen and then they have to go hunt for a client.”

“That process alone says that something is broken, that people aren’t matching up.”

The Chicago Police Database, which Sinclair has been working to develop since this summer, is an attempt to accomplish these goals and to deploy all the information in a way that is engaging and useful. The Database displays all the records of complaints on a map of Chicago. If you visit the site, you can explore the records geographically—by neighborhood, police beat, even school ground. You can also filter and explore by the specific topic of the complaint; allegations of illegal arrest is the largest category. As you explore the database, a graph on the right side of the page displays the proportion of results of the complaints—how many resulted in some kind of punishment for the officer. Scrolling down, names of specific officers appear. If you click on one of these officers, all of their complaints will be displayed, along with all of the officers that have been accused in complaints alongside them.

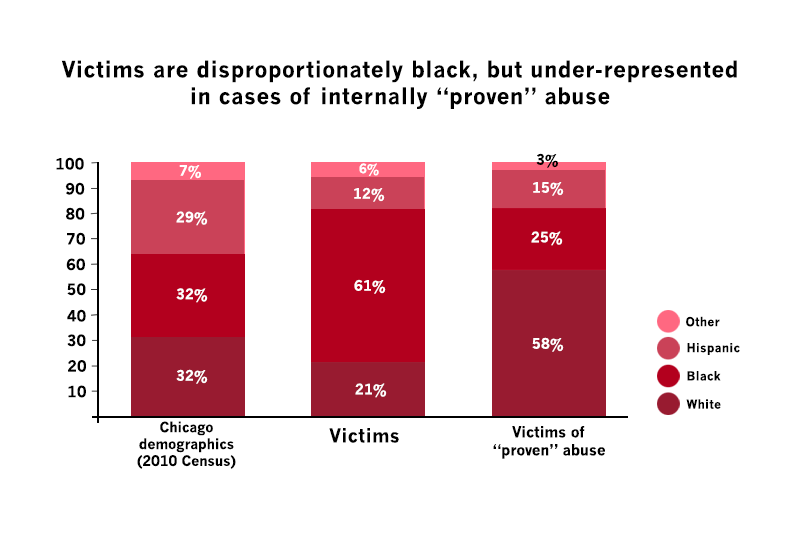

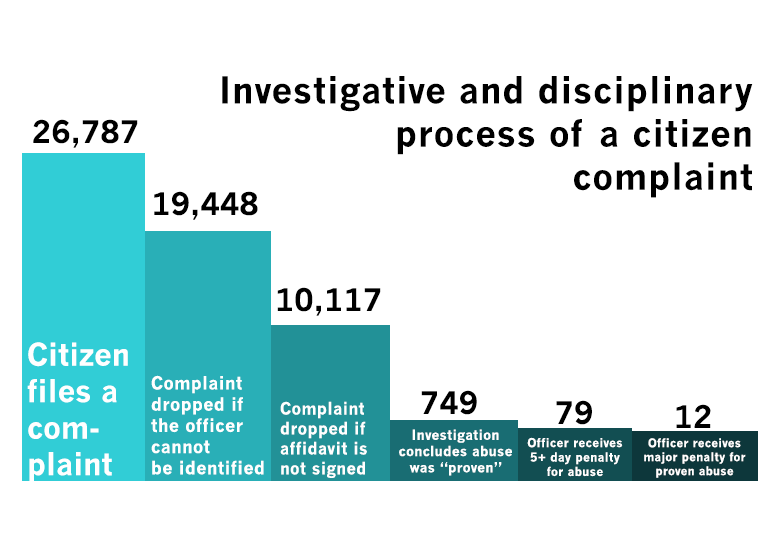

In digging into this information, Sinclair and Kalven have uncovered some alarming trends. Only 9% of the overall complaints were “sustained,” meaning that some kind of punishment was doled out as a result. A surprisingly large number of the complaints were concerning a small proportion of the total officers; of the “repeat” officers (defined as officers with 10 or more complaints) comprise only 10% of the officers on the force but account for 30% of all the complaints. These officers have 16.8 complaints on average, while the average CPD officers has only 4.5. For these “repeat” officers, receiving a punishment for a complaint is even more unlikely than for the average officer. Out of 27,154 complaints against “repeat” officers in the Database, only 1,059—about 4%—were sustained. Even when misconduct is proven, about 85% of disciplinary actions are suspensions of zero to five days. Only 44 cases out of all the complaints in the Database resulted in a “repeat” officer being issued a major penalty—more than a thirty day suspension or termination of their employment.

When Diane Bond was abused in 2003, serious allegations of police misconduct were investigated by the Office of Professional Standards, an in-house office at the Chicago Police Department. In 2007, after charges of bias, the city replaced the department with the Independent Police Review Authority, an organization which, as the name suggests, is supposed to operate independently of the police. In reality, a number of its investigators have been former police officers, some from the CPD.

IPRA, for its part, cites major improvements in handing down punishments in recent years. Their rate of “sustained” findings has risen from 4.32 percent in 2009 to 20.13 percent in 2015. A finding of “sustained” is defined as a complaint where “the allegation was supported by sufficient evidence to justify disciplinary action.”

Larry Merritt, IPRA’s Director of Community Outreach and Engagement, also emphasizes how the percentage of “sustained” allegations is not the only metric of IPRA’s effectiveness. Merritt argues that cases where the officer is exonerated (defined as a complaint where alleged actions were found to have occurred but did not violate CPD policy) or when allegations are deemed unfounded are also what he calls “positive findings,” given that IPRA had enough information to make a definitive decision about those incidents incident. Merritt cites that the percentage of these “positive findings” has gone up from about thirty percent in 2009 to 52.83 percent in 2015.

“Even if you compare twenty percent to police stations around the country,” Merritt says of the rate of sustained allegations, “you know, that’s not that low.”

“But again,” he continues, “it’s not just the sustained rate that determines whether or not we are doing the investigation thoroughly, but instead about positive findings.”

Kalven and the Institute do not believe that the information in the Project alone will bring about reform. But Kalven hopes that public engagement with newly transparent information will change the conversation about police misconduct.

“To say ‘information is power’ is a bumper sticker,” Kalven says. “But what we’re trying to figure out is: what does it actually mean to redistribute power, to make adjustments in asymmetries of power by redistributing information?”

Visit http://invisible.institute

Editor’s note: Darryl Holliday, a member of the board of South Side Weekly, and Harry Backlund, this paper’s Publisher, both work as paid consultants on the Invisible Institute’s Citizen’s Police Project. Neither was involved in the reporting or editing of this story.

Correction: This article has been updated to reflect: that Craig Futterman directs the Civil Rights and Police Accountability Project, that Kalven was represented pro bono by Samantha Liskow as well as Jon Loevy, that CRs are police misconduct investigation files, that the oral argument expected sometime this fall will be before the Illinois Court of Appeals, that Kalven established the Invisible Institute’s first office in a five-bedroom unit on the first floor of one of the high-rises of Stateway Gardens, and that Chaclyn Hunt joined the Invisible Institute after graduation from Law School.