Linda Thomas has lived in Woodlawn for seventy years.

“It’s changed primarily from homeowners and small businesses to parts being re-gentrified and parts just being leveled,” she said on a cold January afternoon. “Developers sort of waiting to see what’s going to go on with the Obama Library, speculating.”

Since the site of Jackson Park was officially announced in 2016, the arrival of the Obama Presidential Center (OPC) has been on this part of the south lakefront’s collective mind, especially here: south of the University of Chicago and just west of the future OPC grounds. Renters in Woodlawn, disproportionately low-income, are likely to be excessively burdened by rent payments—and recent rent increases in the area have unsettled residents’ nerves.

The OPC is likely to be built, but it is not a sure thing. A grassroots effort for a community benefits agreement ordinance—that would impose certain conditions, like rental assistance, local hiring agreements, and property tax freezes on the city, UofC, and Obama Foundation—has stoked fears of displacement among residents. The OPC also faces a looming threat from a court challenge filed by parks advocates arguing against its placement in Jackson Park.

Asked if she is hopeful about the OPC, Thomas said she is. “Hopefully it will bring in business, which will improve not only the neighborhoods [but] the schools, home values.”

“I’m just looking for a better place to live,” she said. “I want to be in Woodlawn with a better place. I want a better environment.”

As sure as Thomas’s neighborhood is at a crossroads, so too is the 20th Ward, which includes most of Woodlawn as well as large parts of Washington Park, Englewood, and Back of the Yards. Alderman Willie Cochran, a former CPD sergeant, has been indicted on federal corruption charges for allegedly shaking down business owners in the ward, and is not seeking reelection.

Much like the current mayoral election, the race to succeed Cochran features a crowded field of candidates facing varying odds. The new alderman will be tasked with managing the repercussions and benefits from the OPC: one of the biggest investments south of the Stevenson Expressway since the 1893 World Columbian Exhibition.

And even apart from that particular fight, the ward faces a host of other issues: Cochran is just the latest in a string of corrupt aldermen, and a fragmented ward map has left many of the residents in the ward feeling disempowered.

Despite all this, Thomas is hopeful. “I’ve been to two forums,” she said, “and I’m enthusiastic, because this is really the most candidates we’ve ever had. They’re younger. They seem to be more enthusiastic about the job. I hope—I hope—I think they’ll be better. They can’t be worse!”

Over the years, though population loss and political decisions have resulted in the ward stretching northwest into Englewood and Back of the Yards—the first mayor Daley sliced up the south lakefront wards in an unsuccessful attempt to hurt the reelection chances of independent 5th Ward Alderman Leon Despres in the 1971 remap—Woodlawn remains the 20th’s political center. Unlike the three other neighborhoods in the ward, nearly all of Woodlawn is in the ward, benefitting the bevy of community groups operating there by allowing them to focus their energies on lobbying one alderman.

Still, “it’s not the same compact ward it once was,” said Dick Simpson, a political science professor at the University of Illinois at Chicago and former 44th Ward alderman. “They were drawing the wards to protect incumbent alderman when they drew them a decade ago.”

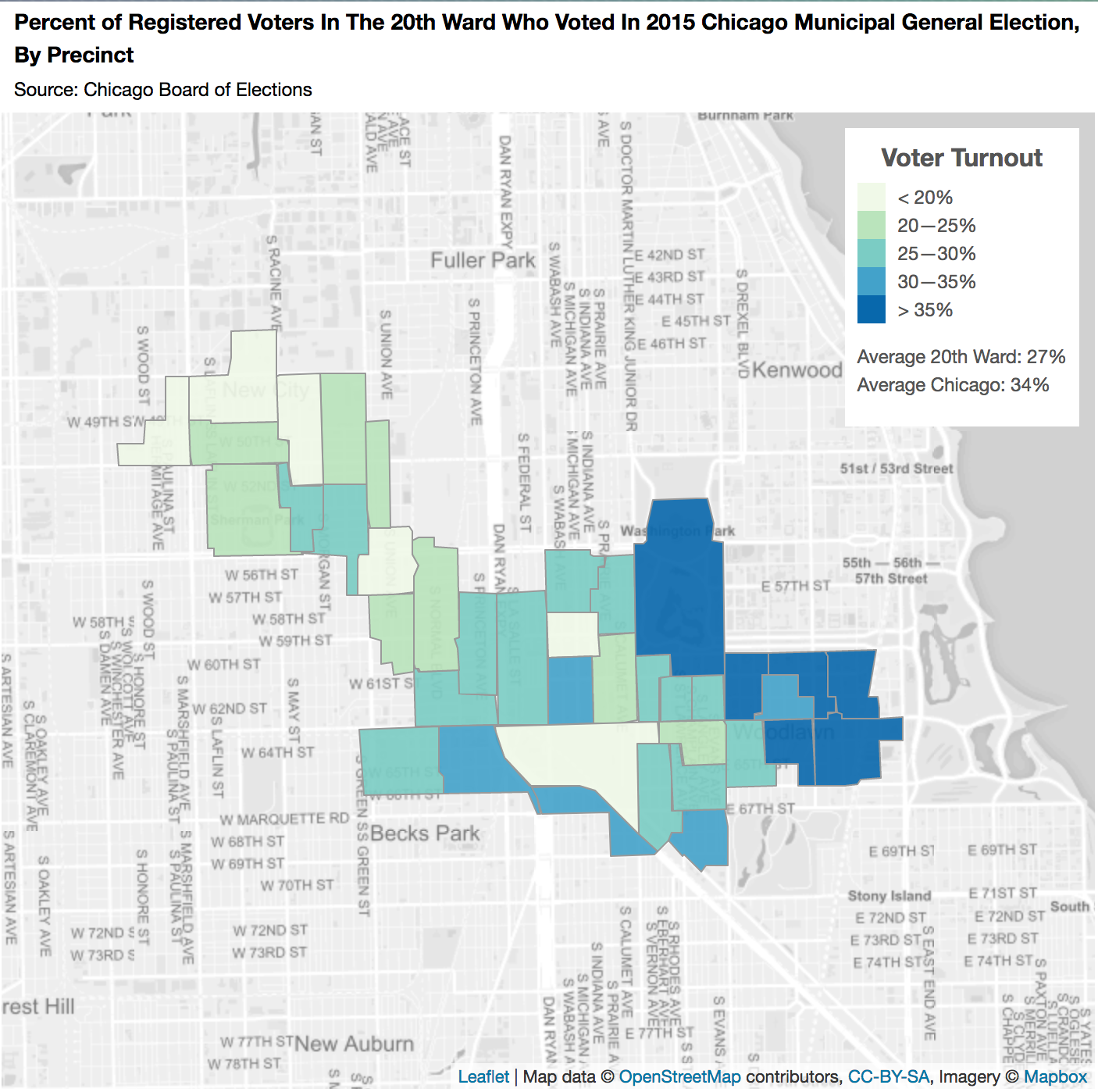

The power differential is clear come election time. Outside of Woodlawn, few people are registered, and fewer come out to vote. Of the four ward precincts with turnout numbers greater than forty percent in the 2015 general election, three of them are in the eastern half of Woodlawn, immediately adjacent to one another. Conversely, few of the precincts in Back of the Yards had turnout higher than twenty-five percent.

That is the result, residents say, of feeling shut out of the democratic process—it also means that aldermen have been unlikely to focus on residents of those neighborhoods.

“It’s a piece of territory that’s been passed back and forth between wards,” said Maureen Kelleher, who lives in Back of the Yards. “I’m hoping for new leadership that pays attention to all parts, and works cooperatively with other aldermen to make sure we’re not seeing the [snow] plow go through one block and not another block.”

All the neighborhoods, though, are tied together by similar economic issues. Woodlawn, once a center of Black nightlife in Chicago, has seen businesses, venues, restaurants, and community centers close up, and housing along with them; between 2005 and 2011, around forty-one percent of the two-to-four unit buildings in Woodlawn, which make up a large portion of the neighborhood’s housing stock, had a foreclosure filed against them, according to the Institute for Housing Studies at DePaul University.

Two of the three community areas in the city with higher two-to-four unit foreclosure rates were Washington Park and Englewood. Back of the Yards has one of the highest numbers of vacant homes in the city—one in six as of 2013—and residents worry about the effects of heavy industry in the area, like the controversial, newly built MAT asphalt plant immediately south of McKinley Park. Residents of all four neighborhoods in the ward feel that their current representatives have not sufficiently taken the community into account in large decisions.

In mostly residential Washington Park, which Cochran shares with 3rd Ward Alderman Pat Dowell, some residents and community groups have felt slighted by the development process of the University of Chicago’s Arts Block along Garfield Boulevard and the $23.5 million subsidized artists’ housing development, supported by over $6 million in TIF funding, down the street.

The TIF money will be funneled through the KLEO Center, a nonprofit run by the Rev. Torrey Barrett, who, with Apostolic Church of God pastor Byron Brazier, co-founded the controversial Obama Foundation-linked development group now called the Emerald South Collective. Some residents of the neighborhood have expressed concern about the prospect of development—last year, Cecilia Butler, president of the Washington Park Advisory Council, worried that the UofC hadn’t done enough community outreach.

And in Englewood—split between six different wards—the issue that’s most directly tied to the 20th has been Norfolk Southern’s expansion of its 47th Street rail yard. The transportation company used its power of eminent domain to displace twenty blocks of 20th Ward residents. In recently-released documentary The Area, residents and organizers strongly criticized Cochran for allowing the project to move forward.

“A lot of folks who watched that Norfolk Southern thing happen are relieved he’s not running again,” said Asiaha Butler, founder of the Residents Association of Greater Englewood. “We all felt as if Cochran’s decisions with Norfolk Southern had sold out a really large portion of our community.”

“Obviously Cochran and his predecessors, some of whom have gone to jail, were not strong,” Simpson said, alluding to the ward’s long history of corruption among its aldermen. In addition to Cochran’s legal dalliances—federal prosecutors charged in 2016 that he shook down business owners for donations and raided a ward charitable fund for, among other things, casino gambling and college tuition for his daughter—his predecessor Alderman Arenda Troutman was herself under federal indictment at the time for extortion, mail fraud, bribery, and income tax evasion.

Troutman was accused of engaging in pay-to-play schemes with developers and locals for her support on zoning changes, building permits, and city-owned land sales. She pled guilty in 2008 and was sentenced to four years. (She was also famously caught on tape saying that “most aldermen, most politicians are hos.”)

Former Mayor Richard M. Daley appointed Troutman in 1990 after her predecessor, longtime police officer Alderman Ernest Jones, died of a heart attack while in office. Three years previously, Jones had beaten the colorful Alderman Cliff Kelley, who was brought down by a 1986 federal corruption probe, having been caught taking bribes, and spent nine months in prison. Kelley now hosts a popular talk radio show on WVON, and last month moderated a forum of the current candidates on economic development issues at the Experimental Station.

Cochran chose to not seek reelection and later reneged on a decision to take a plea deal. Scheduled to go on trial this summer, he has maintained a low profile on City Council, off the public radar in OPC issues.

“It’s really sad that we’ve had aldermen that have got into a little bit of trouble,” said Liz Gardner, a Woodlawn resident and one of the founders of the Woodlawn Community Summit, an annual neighborhood convention. “As we move forward, we have to learn from the past so that we can build a better future.”

Whose vision of a better future will prevail is still very much up in the air. The candidates who will appear on the ballot have a wide range of visions and policy ideas—more accessible outreach to constituents, rent control, and community advisory boards that would approve development, to name just a few. The race has also been rancorous from the start, with petition challenges and criticism about campaign donors fanning the flames. And with nine people running, there’s almost certainly going to be a run-off, further prolonging the election process.

Asiaha Butler said that, as the leader of a community organization, she’s reluctant to support anyone publicly, but she’s intrigued by the race. “It’s gonna be a race to watch,” she said. “Just gotta watch that 20th Ward curse!”

Next week, the Weekly and the Herald will publish part two of this report, looking at the aldermanic candidates’ platforms ahead of the February 26 election.

Christian Belanger is a senior editor at the Weekly

Aaron Gettinger is a staff writer at the Hyde Park Herald