Boy, it’s great to have a microphone, man,” Michael Bryant began, beaming in front of a group of seated onlookers holding on to every word. He was there to share his stories of Maxwell Street Market as part of an event for ‘Poor Man’s Paradise,’ an art exhibit put on by Project Onward, a nonprofit studio space and incubator for artists with disabilities.

An artist and poet, Bryant remembers the Little Italy open air market from the 1960s, which at that point had been a fixture of Halsted Street for about a hundred years, and witnessed its transition from a primarily Eastern European Jewish neighborhood to a fully integrated one where University of Illinois Chicago (UIC) now sits.

Bryant has two art works on display at the exhibition, which lives at the Bridgeport Art Center and was created in partnership with the Maxwell Street Foundation and Project Onward artists who remember visiting Maxwell Street in its heyday. One of Bryant’s artworks is a memory map of the market from the 60s entitled, “Off the #8.”

While speaking to the crowd, the artist reminisced on visiting Maxwell Street at nine years old. At the time he’d seen West Side Story like “ten times in a row” and wanted to be a Jet, one of the street gangs from the musical. “A Puerto Rican Jet,” he said, “but I had a problem. I was a Black guy from Englewood. How do I get to be a Puerto Rican?”

His uncles told him about “a place called Maxwell Street on 13th Street off of Halsted St.” The first thing he noticed about Maxwell Street was seeing all sorts of people, from everywhere. “They got the lingo. They can sell you anything.” And they did. With the help of his uncles, and an alleyway deal, Bryant said, “I not only get the switchblade knife, I get the hat, I get the pointy toe shoes, I get the black pants, and I get the jacket. I’m now a Puerto Rican Jet.”

Nick Jackson, a studio supervisor at Project Onward and curator of the exhibition, collaborated with nine artists to amass a tribute to beloved figures and places at Maxwell Street Market.

Original artwork from studio artists at Project Onward sit at eye level and artifacts from Maxwell Street Foundation are woven around the exhibit.

Project Onwards Executive Director and native Chicagoan Nancy Gomez remembers the smell of Maxwell Street. “I remember my dad driving past it and you could smell the onions. When they [Maxwell Street Foundation] brought their artifacts in boxes, and we were opening up the boxes, you could smell the onions…it just brings me right back there.”

The smell was even present at the event which featured one hundred Maxwell Street Polish Vienna beef hotdogs donated by hot dog stand Jim’s. The Vienna Hot Dog sign is featured at least twice in the show, once as a reinterpretation of the sign using only glitter by the artist Sereno Wilson, who also goes by the nickname Glitterman.

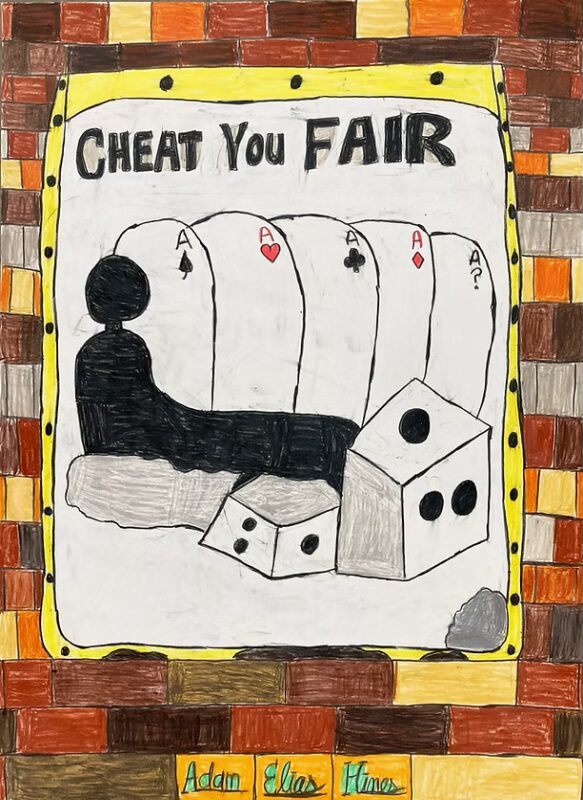

Another artifact featured at the exhibit is a Cheat You Fair sign, which served as the unofficial motto of Maxwell Street Market, and was recreated by artist Adam Hines with colored pencil.

According to Steve Balkin, one of the founding members of Maxwell Street Foundation and professor emeritus of economics at Roosevelt University, the Cheat You Fair sign was affixed to a head shop south of the market. Unlike today’s “corporate capitalism in the United States” whose slogan is “cheat you unfair,” Balkin said, Maxwell Street Market was “small scale, old fashioned, face to face capitalism. You could get cheated because people would sell socks, implying that they were new socks, but they would have holes in them, but you had a chance to examine them. And you could get faked and cheated, but you had a fair chance of not getting cheated. So that was cheat you fair.”

A haven for immigrants arriving in the city, Maxwell Street developed as a third space and business incubator. You could arrive on a Monday with nothing and set up shop on Tuesday. According to Balkin, it was $25/year to vend, but if you set up shop on the outskirts, it cost nothing.

Jackson was introduced to the market while attending The School of the Art Institute of Chicago in the 2000s. “I was looking for cheap weird materials to use to make sculptures.” There he met artist Tyner White and fell into the world of Maxwell Street Market.“There was a benign madness to it,” Jackson said. “It had all of the spontaneity, all of this mixing of unexpected contrasts and combinations.”

Jackson ensured almost every artist featured in the exhibition has personal memories of Maxwell Street.

George Zuniga frequented Maxwell Street in the early to late 1990s with his mother. His piece in the show, “Johnny Dollar and the Catfish Stand,” is an homage to the catfish stand he remembers, as well as the associated blues stand where live musicians played outside.

Sculptor Ricky Willis has three pieces in the exhibit: “The Scrapper Truck”, “Mattress Shopping”, and “The Blues Bus.” Willis “embodies the Maxwell Street philosophy because he’s a true recycler,” Jackson said. Made with cardboard and paper, with the speaker on the back, made from Willis’ own insulin vials “The Blues Bus” depicts the real life Maxwell Street Blues bus, formerly the “Mississippi Delta, Blues Bus” owned and operated by John and Marie Johnson in the 70s and through the early 2000s.

According to Laura Kamedulski, Secretary and President of the Maxwell Street Foundation, the Foundation has been working on preserving the bus since the 1990s. The bus has been subject to vandalism and in 2018 the whole front end was stolen. The Foundation decided to do a “rear-ectomy,” as Kamedulski called it, where they removed the rear end of the bus. The Foundation has been in talks to preserve the artifact for an exhibition on Maxwell Street Market at Chicago History Museum.

Music, and specifically the blues, was an integral part of Maxwell Street. In order to be heard over all the market din, electric guitars would be plugged in outside storefronts. One of the last remaining blues musicians on Maxwell Street, street legend Vince “Lefty” Johnson,” played after the exhibition talk while visitors chomped on Vienna beefs and milled about with the artists, adding to the cacophony of the exhibition. I felt the spirit of Maxwell Street alive in the place.

Andrew Hall’s “Looking East on Maxwell Street” is a painstakingly detailed work of art, all done using markers. Hall works a full-time job and comes in at 4:30pm everyday to work the last 30 minutes of the Project Onwards open studio hours (Tuesday–Saturday, 11am–5pm). “It may appear to be in black and white. It’s actually a series of grays,” Hall said, a beautiful metaphor for life.

Bill Douglas has two pieces in the show: “The End Of Maxwell Street” and “The Chicken Man.” Douglas went to UIC in the 90s and would walk around Halsted and go to Maxwell Street to eat. “It was a nice little place,” he shared. “The Chicken Man” depicts a legendary figure of Maxwell Street. According to Douglas, he “would have a little chicken on his head and play the harmonica. At the same time he also would wear a string with beer bottles, baby dolls, stuff like that and then would use that string to have the chicken walk the tightrope.” Douglas said he “tried to put a twinkle in the chicken man’s eye because he seemed like he was having such a good time,” a true entertainer.

Jackson said one take away he’d like visitors to leave with is the tragedy when “vital parts of places, identity, cultural identity, get lost, and get papered over.” One of the things that artists can do is to keep the memories of vital places alive and hopefully “create some curiosity.”

If you’d like to support Project Onward’s work, you can visit their donation page here.

Poor Man’s Paradise closes at 5 pm on September 27.

If you’d like to learn more about Maxwell Street Market, you can visit maxwellstreetfoundation.org

Maxwell Street Market is back in its original location, October 5, between S. Halsted St. and S. Union Ave. 10am–3pm, free admission.

Delaney Eubanks (they/them) is a writer and photographer based in Chicago, IL.