At what point did we start thinking that we needed more colors than there [already] are in the world?” asks Christina Mackie in her artist’s talk. This, she reveals, is the basic question behind her new multimedia exhibition—entitled “Colour drop”—at the Renaissance Society, which held its opening reception this past Sunday and will remain on display until the end of June.

The exhibit, which is co-curated by Associate Curator Hamza Walker and Executive Director Solveig Øvstebø, is Mackie’s first exhibition in the United States (she’s Canadian-born but now based in London). When Mackie speaks of the “immanent possibility of color,” as she did during a conversation with Walker, she is referring to the literal mutability of pigment, and to the many dyes and textures in which it can find expression. It’s an idea that is readily apparent in the exhibition’s manifold figures, ceramics, glasses, rocks, and paints. It is colorful, to be sure, but never wildly chromatic.

Walking around “Colour drop” feels a little like positioning yourself in various visual landscapes, three dimensional paintings that bring together color and form with all manner of materials and objects. With each object in the exhibition, Mackie engages different colors and ideas, or in her words, “taking what you know and bringing them to bear on materials.”

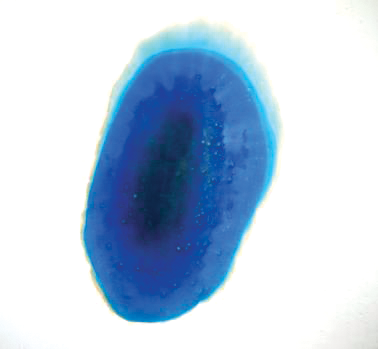

The room’s centerpiece looks like three mammoth-sized dream catchers— really just nets—hang from the ceiling on various pulleys. The bottom halves of the nets, like draped hosiery, are soaked in paint and remain suspended just above their respective pools of paint, one red, one blue, one yellow. “I was really aiming for this almost accidental placing, the sedimentation, the evaporation, and then you stand it up,” Mackie explained, referring to the way the soaked nets have since settled.

Elsewhere, on a table, there are five ceramic pieces that resemble giant eggs strewn over ceramic squares. Altogether, it looks strangely prehistoric. The inspiration for the piece, Mackie said, came from “very, very old paintings… done in five colors” that she had seen on top of rock pallets in Northern Australia. Like the ancient paintings, she insists that most of her art look “synthetic” or “man-made.”

Like much of Mackie’s work, “Colour drop” resists brusque characterization. The eponymous “drop” of the exhibition’s title could refer to a number of different objects in Mackie’s exhibition. On two separate walls, two and three respective planks of gesso-plastered wood lean against the wall. Each is flecked with several drops of different watercolors, a medium that Mackie says she likes because of its “mineral quality.” A few of these drops are painted atop a slight physical divot in the wood, giving depth to the already palpable colors. The wood structures are actually composed of two asymmetrical panels, one resting on top of the other, that together make the leaning planks just slightly unparalleled. At a distance, the effect is subtle but intriguing.

As an amalgamation of various colors and materials, “Colour drop” feels like a discursive stroll through Mackie’s own mind. Much of the placement in the exhibition is characterized by a degree of randomness. “I like the accidental,” Mackie admitted to Walker during their conversation. “If something is beautiful, it’s kind of an incidental aspect of it.”