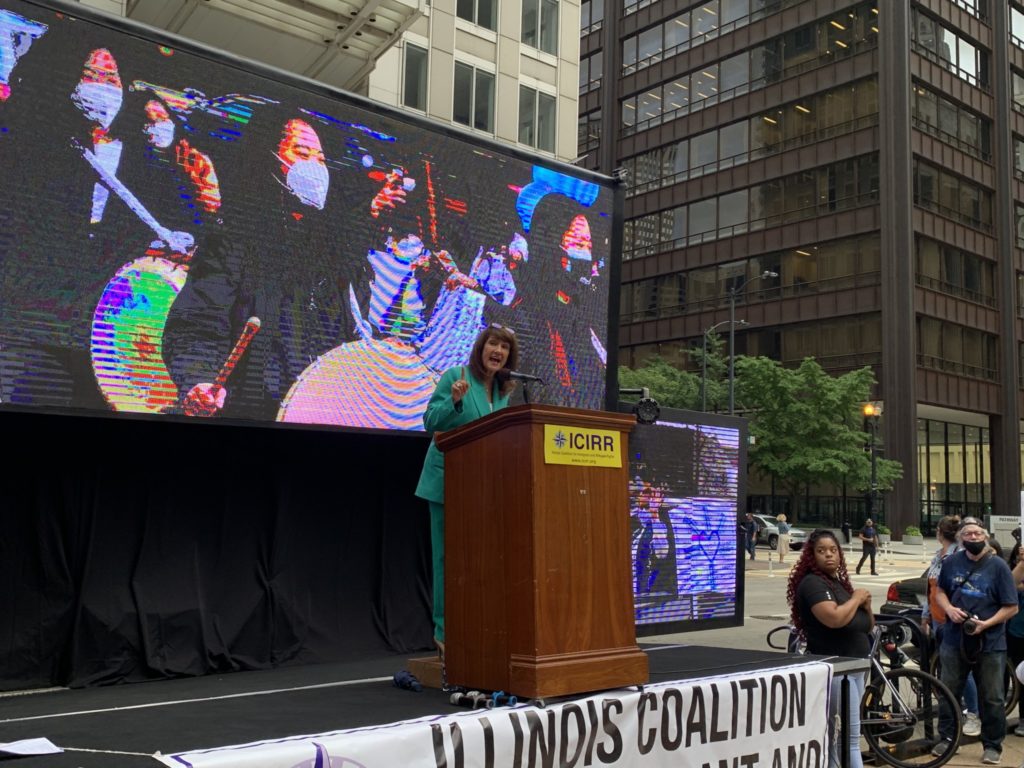

“I am tired,“ said Elizabeth Cervantes from the podium at an immigration rally outside the Thompson Center in downtown Chicago on July 8. “I’m tired of waiting for the right moment to have the same basic rights as everyone else. How much longer must we wait?”

A pathway to citizenship would prevent the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA)—a policy that provides temporary relief from deportation as well as work authorization to approximately 800,000 undocumented young people across the country—from constantly being attacked and suspended, advocates say. Just last Friday, July 16, a federal judge in Texas blocked new DACA applications. U.S. District Judge Andrew Hanen, along with a group of states suing to end the program, argue that it was illegally created by former President Barack Obama in 2012.

This was a fear expressed by people who attended the “We Can’t Wait” rally to push citizenship for all and a stop to deportations. Organizations such as Casa Michoacán, Arab American Action Network, Coalition for a Better Chinese American Community, Alliance of Filipinos for Immigrant Rights and many more attended the event and lifted colorful signs that read “We Can’t Wait”, “End Deportations” and “Citizenship for All.”

The lawsuit against DACA, which was filed in November 2020 during Donald Trump’s presidency, claims that states face irreparable harm because they bear extra costs from providing health care, education and law enforcement protection to DACA recipients, but makes no mention of their value to the economy or the pandemic as essential workers. Research from the American Action Forum (AAF) shows that granting DACA recipients work authorization has resulted in huge economic benefits. An estimated 380,000 employed DACA recipients contribute an average of $109,000 each to GDP per year.

The decision is not expected to affect current DACA recipients, only those applying for the first time.

At least five million essential workers have played a crucial part in the country’s pandemic recovery. Despite it, essential workers who are undocumented have been largely excluded from COVID-19 relief, are subject to exploitative working conditions and more than two-thirds of U.S. undocumented immigrant workers serve in frontline jobs in essential industries. “These essential workers should have a path to citizenship in the country they call home. They have been there for all of us, now it’s time for all of us to be there for them,” Illinois Rep. Congressman Jesús “Chuy” García (D) said.

“Yesterday’s DACA ruling was a wake up call,” said Marcelo Ferrer, director of immigration services for Logan Square Neighborhood Association. “We are tired of the turmoil that our DACA brothers and sisters have endured for the past couple of years. That is why we are calling on Congress to pass either a standalone Dream Act or include immigration reform in the budget and pass it through budget reconciliation. We are in the fight of our lives.”

At the rally, activists from the non-profit Brighton Park Neighborhood Council chanted “La gente unida, jamás será vencida (The people united will never be defeated).” They wore orange shirts and banged pot lids, tin cans and wooden spoons. The crowd at the Thompson Center chanted along and held up their fists under the summer phosphorescent sky.

“The first time I attended an ICIRR rally to demand citizenship I was a twenty-year-old undocumented college student, and here we are still fighting…”, said Cervantes. Now she is thirty-two years old and protected under DACA. In addition, Cervantes sits on the board of ICIRR (Illinois Coalition for Immigrant and Refugee Rights) and believes there is a real chance to pass an immigration reform bill that creates a pathway to citizenship for millions of working immigrants. “We have an opportunity…but we need our members of Congress to fight. They won’t do it unless we push them.”

During his presidency, Trump threatened the rights and freedom of immigrants and refugees, as he pointed the finger at immigration as one cause of a declining future for white working-class and middle-class Americans. He repeatedly criminalized Mexican immigrants to justify the creation of a wall on the Mexican-U.S. border and reinforced the detainment of thousands of Central American children seeking asylum.

In 2017 he imposed a travel ban that prohibited issuing visas to immigrants from seven largely-Muslim countries, and in 2020 he expanded that to thirteen. For four years, advocates had to defend DACA from Republicans who wanted to dismantle the program. In 2017, the Trump administration abruptly ended the DACA program, triggering multiple lawsuits challenging it. The United States Customs Immigration Services (USCIS) rejected all new and renewal applications received after that October. In 2020, the Supreme Court ruled that the Trump administration could not carry out its plan to shut down the program because it failed to give an adequate justification.

Now under Biden, progressive politicians believe they have the clout to pass immigration reform and are leaning on budget reconciliation as a way to get it done. It takes at least sixty votes to pass a bill through the Senate, but budget reconciliation provides another way to pass legislation with a majority vote in the House and Senate during a process that takes twenty hours. This process is typically only utilized when the same party controls both chambers of Congress and the presidency.

A few weeks ago, García announced he would not back the budget reconciliation if it did not include a pathway to citizenship. “We have The White House, Senate, and House—the moment is now,” he said.

Over 30,000 active DACA recipients lived in Illinois in 2020, according to the American Immigration Council, and 400,000 undocumented immigrants lived in Illinois in 2016.

García told the Weekly he expects the bill to focus on a pathway to citizenship for DACA youth, immigrants under the Temporary Protected Status (TPS) who are confronting armed conflict or environmental disasters in their country, farmworkers, and other essential workers. A bill introduced in February defines the type of essential work. Undocumented immigrants working in healthcare, manufacturing, domestic work, food and hospitality, warehousing and more could be eligible.

“We are encouraged to see Senate Democrats responding to the calls for a pathway to citizenship happening here in Illinois and across the country,” said Brandon Lee, the communications director for ICIRR. “While this is a critical step, we are still early in negotiations with many steps to go before a final budget is passed. What we know, however, is that organizing is working…”.

In Illinois, a bill that would close ICE detention centers and limit the way police interact with ICE is expected to be signed into law by Governor J.B. Pritzker later this summer. Pritzker attended the rally at the Thompson Center and promised to sign the bill that would make Illinois the third state to end detention contracts with ICE. “Our moment is now. I want our immigrant community to know that Illinos is and always will be your home,” he stated. But advocates worry because this won’t stop deportations, only interrupt them.

The last time there was a pathway to citizenship in the U.S. was thirty-five years ago when then-president Ronald Reagan signed a sweeping immigration reform bill into law. It was sold as a crackdown; the bill enforced tighter security at the Mexican border and penalties for employers that hired undocumented workers. However, the amnesty allowed permanent residency for about two million immigrants.

If the pending policy would only apply to DACA recipients, TPS holders, farmworkers and essential workers, it would still leave out people like Bo Thai of the HANA center in Chicago, a non profit that empowers Korean, Asian and multiethnic immigrants. Thai is not eligible for DACA because he arrived in the U.S. in 2009. One of DACA’s rules is that applicants must have lived in the U.S. since 2007 up to the present time.

There are strict rules to qualify for DACA. For example, the U.S. government will not grant DACA to people convicted of either a felony or what USCIS calls a “significant misdemeanor“, such as burglary, unlawful possession or use of a firearm, driving under the influence of alcohol and others. Additionally, people do not qualify if they do not have a high school diploma, GED or are not enrolled in a program to obtain a GED. Applying for DACA is also a huge expense to undocumented immigrants and they must renew every two years at a cost of $495 each time.

“Being undocumented has shown me that I don’t have access,” Thai said.

He has struggled to find work and healthcare and cannot obtain a driver’s license because of his status. Thai came to the U.S. at the age of thirteen to live with his aunt and uncle, but his relationship with his parents and other family members greatly deteriorated after the separation.

On the day of the rally, Thai said he got a call with the bad news that his friend’s DACA had expired and got fired from his job. “This is a reminder that DACA was never enough,” he said. The Migration Policy Institute has estimated there were about 11 million undocumented immigrants in the U.S. in 2018. However, less than 10 percent of the undocumented immigrant population qualified for DACA.

Thai thinks the program has pinned the immigrant community against each other. “DACA creates a narrative of good immigrants, who are deserving to be in this country because they are highly educated, versus bad immigrants,” he said.

While immigration advocates like the ones present at the downton rally said they want citizenship for all, Illinois Rep. Jan Schakowsky (D), like García, alluded to the fact that all may not get it in this bill. “But we will get it, and we will get it this year,” she said.

Illinois Rep. Marie Newman (D) said at a minimum there should be a roadmap for DREAMers and essential workers, but that it does not end there. “The fact that we have to ask for a pathway to citizenship [for essential workers] is ridiculous. They got us through the damn pandemic for God sakes. We will get everybody a pathway to citizenship.”

At the rally, both Schakowsky and Newman vowed they would also push to reduce excessive funding from ICE and the U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) and the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) and invest them in community projects to promote citizenship.

They also both committed to putting pressure on the secretary of DHS, Alejandro Mayorkas, to greatly limit who is a priority for deportation through prosecutorial discretion.

The drummers from the HANA center gathered at the front of the stage, beating their drums and banging their copper cymbals. In 2006, these same streets the largest pro-immigrant demonstrations in Chicago’s history with hundreds of thousands of demonstrators taking to the streets for the very same rights that never came. Chicago was the initial impetus for many of the immigrant rights protests which followed throughout the country that year.

Afterward, people marched to the Federal Plaza, and on Wabash Ave., amongst the crowd a mother pushed her baby in a stroller. To her side was her young daughter raising a sign that read “Legalization for All” drawn with pink hearts around it. Her mother held up her fist in solidarity. Children and youth from the United African Organization held up banners and chanted, “Abolish ICE“. Like they did in 2006, the crowd raised a multitude of signs in the air again, but one was new, “We Can’t Wait.”

Alma Campos is the Weekly’s immigration editor. She last wrote about the vaccine disparity in the south suburbs.