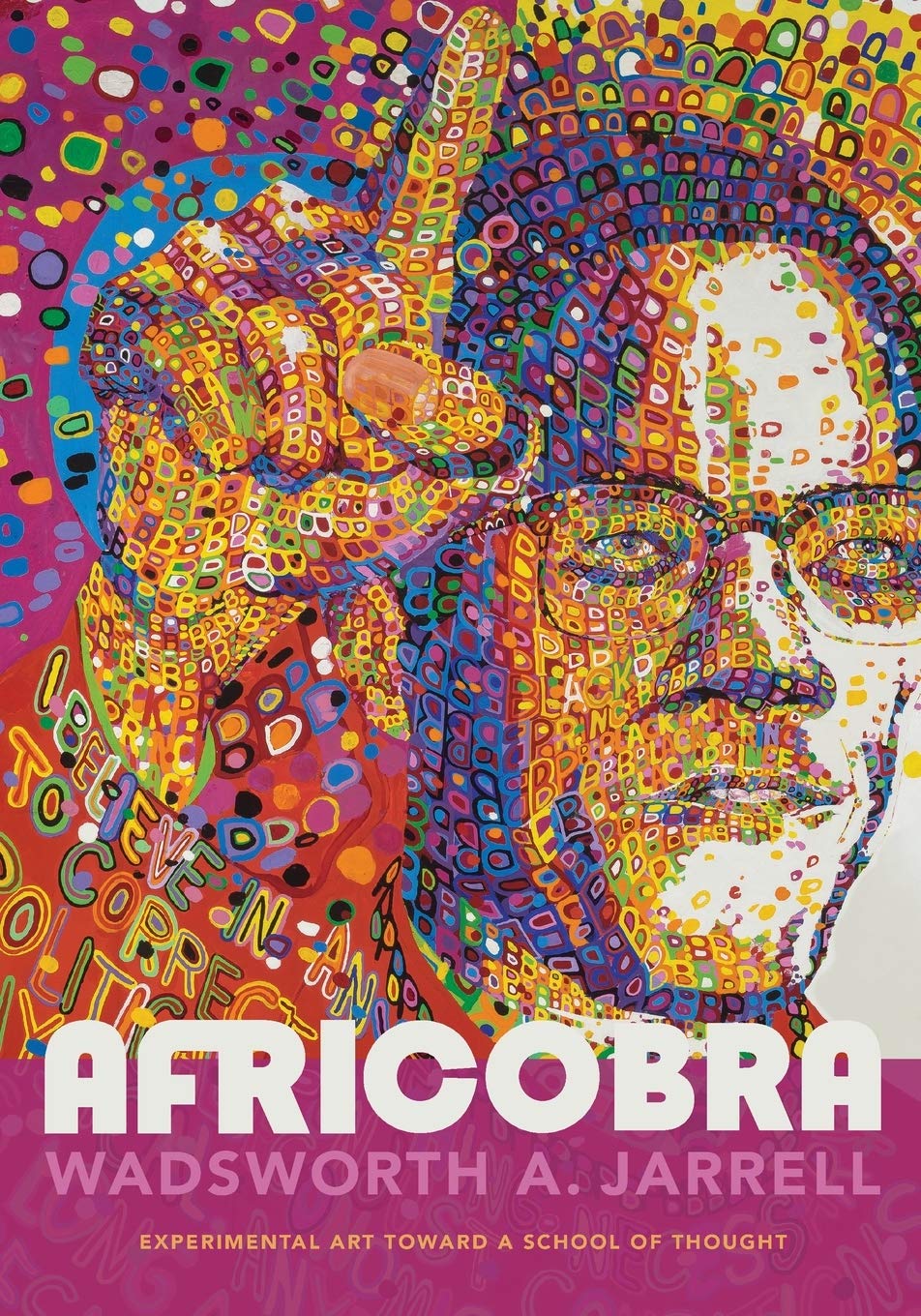

A little over fifty years after AfriCOBRA’s founding, the new book AFRICOBRA: Experimental Art toward a School of Thought (Duke University Press, 2020) works to provide an inside view of the African Commune of Bad Relevant Artists, the groundbreaking Chicago arts collective. Written by founding member Wadsworth A. Jarrell, the book describes the collective’s early years, as well as its relationship to history. Springing out of a small studio space on the South Side, AfriCOBRA was deeply embedded in Black Chicago culture—representing the community they lived in as well as cultivating a larger Black aesthetic that was absent from the mainstream art scene and imagination.

The book describes many of the central art pieces in AfriCOBRA shows and deftly chronicles the political mood of the sixties; how a time of change informed a revolutionary arts movement. AfriCOBRA’s objective, as detailed by its radical philosophy, was to reject Western artistic standards and create a Black arts movement borne out of the community. In the pursuit of this goal, the group’s work followed a set of principles that made its work immediately recognizable, including the use of “Cool Ade” colors, free symmetry, frontal images, and “shine.”

Throughout the book, Jarrell expressed disdain for the boundaries and descriptions of AfriCOBRA’s art provided by outside writers and critics. Jarrell is interested in pieces speaking to the viewers without mediation. Many of the conversations that the group had in the early days are detailed in the work, with dialogue taking center stage in discussions of program, philosophy, and individual artworks. It is important to highlight what was said and who said it. The discussions explicate the cohering of AfriCOBRA’s artistic philosophy and pushed each artist in their creative process.

In December, I spoke with Chicago-born artist and founding AfriCOBRA member Gerald Williams about the first years of the collective and his reactions to the book, and the through-lines that connect their work to our present moment. After traversing the globe for many years, Williams returned to Woodlawn in 2015 and currently lives on the South Side.

The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Why a first-person narrative on the founding of AfriCOBRA? What is the value of someone writing from the inside about the founding of this art collective?

Gerald Williams: Well, you can get a perspective that you wouldn’t get otherwise, because everything, everything that’s been written about AfriCOBRA comes from another set of eyes, you know, so people write different things. And there are things that have occurred that have been incorrect, something as simple as the location of The Wall of Respect, for example. It was at 43rd and Langley. But I’ve seen 47th and Langley written and some other locations, so, you know, it’s important where it was located. So you just kind of like extrapolate that out and see that there’s possibilities for a lot of other things being incorrect or incomplete.

So, AfriCOBRA created a philosophy and set of artistic principles which informed the works that the group created. What was it like to change the way that you are painting and follow this new philosophy that you came up with other people collectively?

GW: One of the first paintings I did when the five of us got together was a family eating dinner. The subject was “The Black Family.” It was addressed as being a perpetuation of the Renaissance view of portraying a group—always having to be in some kind of setting. You know, like the Last Supper or people sitting at a lavish feast or something like that, there were not a lot of alternative viewpoints in the models that we looked at. There was the idea of maybe the best way to learn how to paint is not to look at anything else. So, we kind of tossed aside the other perspectives as much as possible. And we felt like we were reaching back in our own heritage.

We look back to Africa and the kind of work that was done in Africa. Picasso and Braque and a whole bunch of other artists started studying the work of African artists, who at that time were not even called artists. Their work was not fine art, it was craft. The early attempts to go that way, to adopt African forms and ways of portraying people in the twenties and thirties here in the United States, they were dismissed as being unacceptable. I remember an early exhibition at the Harmon Foundation that was reviewed that included a lot of Black American artists, and it was looked at dismissively. Well, that didn’t necessarily happen with a European artist who did virtually the same thing. So, we decided to look at the features of Black people and the work that they have produced and performed. Singers, musicians—they always have a distinctive form of expression, whether gospel music or blues or jazz. So why shouldn’t we?

We had a meeting where we decided to look at the work that we had done just prior to becoming members of AfriCOBRA, even before AfriCOBRA was even thought of as being an organization and we were just brainstorming and talking about what is going on in the world around us. We decided to focus on producing imagery that was positive and uplifting and not depressing or expressing depressing thoughts like slavery. So, we decided to do a painting of the Black family, which was my introduction in how not to paint. Everybody brought out a piece and we critiqued it. And ironically, everyone did a portrait of a family as a group with a man, woman, and two kids. The significance was not so much the subject, the subject was there, but how do you paint this family? It was a portrait still. So, I did a second one with the family in a group setting. It was the way in which they were painted that was significant. The idea of a unity of the family as a unit was there and it was pretty much cliché. You know, just being honest about it, it was a cliché. It’s called Say It Loud and we included wording and lettering in the work, and that is what made it distinctively different from anything else that anybody in any other culture had done. Using lettering as unbalancing, and no setting or background. It was the signature element of AfriCOBRA from that point on, and we decided that we could always work within that mode. And like everything, you know, there’s an evolution that takes place.

I’m interested in how dialogue and criticism functioned in the process of the collective, how that worked, how important that was. It seemed to me that that figured pretty heavily in your process and in the work itself.

GW: We just started off from the perspective of artists who were living in the midst of a lot of changes that were going on and within the culture at large and our community especially. I remember one of the very early meetings where the subject of Black expression came about and how there are ways that we sing that are unique to us. The articulation and in how words are expressed and the difference in intonation and so we kind of said, well, how does something like that apply to visual arts? Are there ways that we express ourselves visually that are unique and intrinsic to Black Americans, to Black people? We have some unique sensibilities and understandings about where we came from and how all of that works itself into how we exist. And then they got elaborated upon in many ways.

Was it about finding the expression of a new voice in visual art?

GW: Well, not especially a new voice, the voice was always there, you know. The Black Power Movement was as much about discovery and rediscovery and inward searching as about the political implications of what Black power meant, but that was key. But it was identity and expressing that identity—clarifying the identity and expressing it in ways that were reflective and gained some kind of universal understanding of what creative people can do. That whole period of time was about rediscovering that voice that was always there.

When you look at the mainstream culture there was no voice. You know, I’m thinking about how when my generation looked at television, it was very limited. You didn’t see any Black commercials until the sixties and seventies on TV and the commercials kind of reflect the whole culture. But it omitted, it didn’t include a lot of the culture that I saw as I looked out my windows and, you know, walked down the street and so forth. The sixties and seventies ushered in an era where our worldview became important. Not just for the world in general, but for our own community that we don’t all think alike and act alike and even have the same dreams.

How did you balance trying to represent and strive towards this transnational Black aesthetic with the smaller goal of representing your own community, the people on the South Side?

GW: It’s something that kind of like comes from your vision—what you see, think, feel, and want to tell others about. And that maybe can lead some people to think that what they think, see and believe in and experience is not important enough to put out there for the whole world to see. And it is like the store down the street is not a “work of art” unless you bring it to the forefront as part of what you see. In a way, artists want to look at and express the city on the hill, it’s bright and shiny rather than what’s down the street. And this has been the reality of mainstream culture, the beautiful architecture and beautiful gowns. That always was what filtered down and was the sort of thing that the artist ought to reflect or focus on. That paradigm was blown out of the water when we started talking about how the standards of beauty are the ones that are promoted. As opposed to our worldview, which was always, you know, put into a negative connotation. All of the existential elements that we dealt with every day were dismissed as too limiting.

What were you guys able to achieve as a collective that you wouldn’t have been able to just as individual visual artists pushing the envelope?

GW: Working as a collective was the key. Artists generally work alone, you know. I don’t like anybody seeing anything that I did until it’s finished, but we decided to just bring unfinished work and talk about it, you know, determine where is this piece going? What do you want to do with it? It was a collective of ideas, a collective of thoughts and feelings and understanding enough about our history and where we came from and the state of our own existence. Today, a collective is also perpetuating the idea that there’s strength in unity. And creating one out of many. So we forged that bonding out of a collection of thoughts, feelings, sensitivities, and products.

How would you characterize the legacy of AfriCOBRA?

GW: I feel much better listening to what other people think. Because I think we were the baddest things. Nobody could touch us. Nobody can touch us today. AfriCOBRA is an open-ended idea. You know, we threw all this together and said, “OK, now go home and play with it and see what you can come up with.” And that’s the legacy, I think is to challenge others to take something that is there and challenge it with your own insight and perspective and sensibilities and talent. You’re not going to produce the same kind of work that we did then. Because I think we have evolved from that.

I think that the legacy itself, is creating something that didn’t exist before and fostering the idea of coming up with a whole new milieu. When I did a couple of art fairs when I first came back to Chicago, I had some older, original work just hanging in a booth and there were a number of people who passed by and stopped saying, “Oh, AfriCOBRA,” because they recognized that style and because we showed it in Chicago and kind of gained a reputation here. So, anybody coming through, you know, saying something about AfriCOBRA would immediately respond to something they had seen. And that was like fifty years ago.

What was it like to come back to Chicago in 2015 after being away for so long?

GW: You ever read the book You Can’t Go Home Again?

No, I haven’t.

GW: It’s a novel written by Thomas Wolfe in the 1920s, 1930s. He was from the South and went to study at Harvard or Yale, one of those schools. But that idea of, “you can’t go home again.” It’s very real. Try it sometime. I don’t know where you’re from, but Chicago, it’s a different world. Now, when I left, it was always kind of rough and tumble and it had that reputation and that notoriety from the early days of unpaved streets and sidewalks. It’s evolved. You know, there’s the glitter and gleam of the downtown, the skyscrapers, stack boxes on the Midway across from gothic edifices.

But I ask myself all the time did Chicago lose more than it has gained? Because when I left in 1973 there were not 190 people being shot over the weekend. The violence is uncontrollable as it was back then, but it seems to be a lot, a lot worse. This particular neighborhood right where I live reported no shootings in the last year. A couple of weeks ago, I was walking the dog and a guy was sitting in a car, he just got shot. So, to me, there are some days it feels like déja vu. Other days it feels like things are going to get better and there’s progress. And I’ve been back now for like four years and this neighborhood has one square mile area of a thousand residential structures. Twenty-five percent of them were vacant, abandoned, or whatever. Nobody is living there. Some have signs of growth, you know, even as we speak. I can point out about four or five developments going up. And I always said, well, look.

I spent three years in Japan. I lived in Europe and went to Germany many times. And when I came back, I said, how could Germany and Japan be completely rebuilt to the point of being world leaders in less than twenty-five years? They rebuilt downtown Chicago. It was never bombed. No, it was the ghettos that were encroaching upon it. Taxpaying American citizens helped to rebuild Japan and all of Europe. And here is this, this area right here on the South Side, the rubble has been removed but it’s still a war zone. I feel that I can do more by going out and picking up all of the garbage. I do that about an hour every month. I’m not saying that I’m better at picking up garbage than producing artwork but I get a great deal of inspiration doing both. The art world in this community used to be very active, you know, AfriCOBRA was born in the Woodlawn neighborhood. Wadsworth J., Barbara Jones—Barbara grew up a few doors down from where I live right now. There were a lot of artists in this area who were working, several galleries. But now there’s not even [one] gallery.

Do you see any similarities between the political movement in 1968 and our present current political moment?

GW: I think you have to try to think in a long-range view. You might think of them as being mileposts in a revolutionary process. In the 1960s, we were in the middle of the civil rights movement, this “Black is Power” cultural movement. And it was a period of discovery and rediscovery of what a God was behind us, and fostering the idea that that Black is not a dark, ugly thing, that it permeated our own being and existence, that Black is beautiful. That we can empower ourselves to do whatever needs to be done. As long as there’s the will and the understanding and the education to work at it. The sixties built all of that.

Caleigh Stephens is a writer in Hyde Park, as well as an editor, dancer, choreographer, and dog walker. Their writing focuses on literary criticism, art history, and political happenings. This is their first piece for the Weekly.