Bill Siegel’s new documentary, “The Trials of Muhammad Ali,” introduces us to Ali as an Olympic champion. In a truly impressive collection of footage, he is seen standing on the Olympic podium, discussing his boxing prowess with reporters, and generally declaring his invincibility to the world. In 1960, at the age of eighteen, Ali was already threatening to become the World Heavyweight Champion. Siegel sets the scene primarily through the words of equally arrogant white reporters: Ali will never do this; he’ll be beaten to a pulp; why can’t he stop talking for one minute? Of course, Ali shocks the world (but not the audience) by trouncing the reigning champion, Sonny Liston.

Yet Siegel makes it seem like this enormous upset neither required nor produced any personal growth. We never see the drastic physical and mental transformation that one usually associates with training athletes, even when Ali is preparing for the fight. There is no footage of him struggling, physically or emotionally. Ali’s strong character is portrayed as an eventuality or a permanent entity, instead of a real achievement or a process.

In one of the best boxing scenes, we see Ali’s fight against Ernie Terrell, another famous black heavyweight, who refused to use Ali’s chosen name. In typical Ali style, this existential battle is settled in the ring, and as Ali pummels Terrell into submission he repeatedly shouts, “What’s my name!” Perhaps Ali’s certitude and constancy is in itself an argument for the things that he believed in: black power, black manhood, and the freedom of religion. All of these rely on a strong sense of identity, a pride and courage that comes from knowing who you are. Thus, Siegel equates conviction with permanence, a sense of self with a stasis of self.

Even when Ali converts to the Nation of Islam and takes on a new name, it’s treated more as an eventuality than a change. He rejects his “slave name,” Cassius Clay, and then receives his new name, Muhammad Ali. For Siegel, this new name embodies all of the ideals Ali stands for after joining the Nation, all of the convictions that he now adopts as his own. But Siegel’s romanticized notion of Ali’s name as the expression of his true self seems bizarre, once it is revealed that this name was actually given to him by Elijah Muhammad. Does Ali ever doubt himself? Does he ever question the authority of the Nation of Islam? In transitioning from a simple athlete to a political hero, does he ever really change?

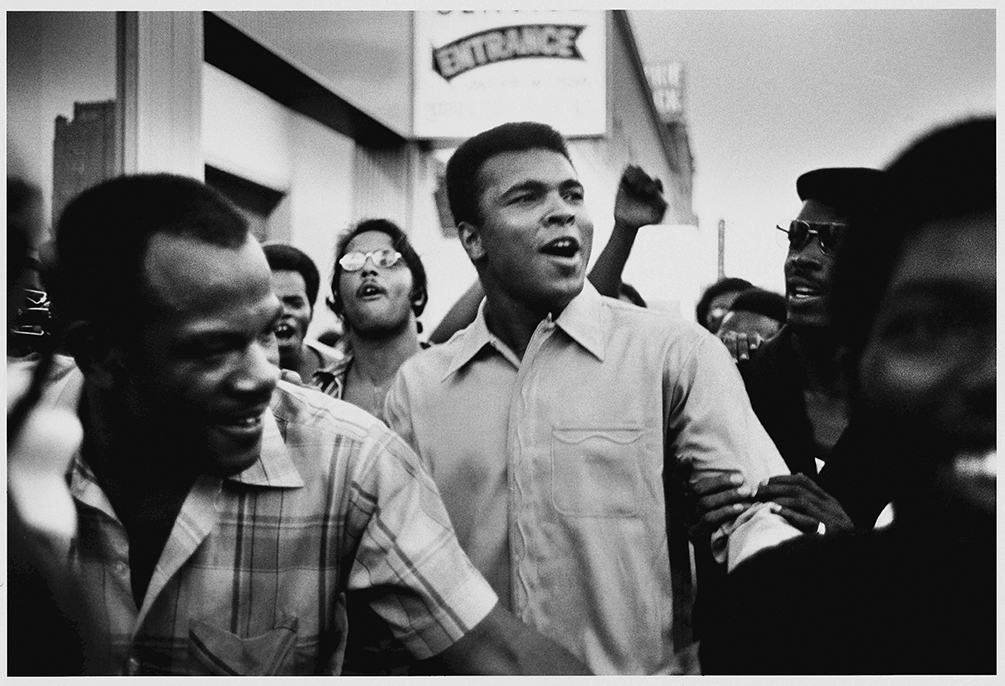

Siegel then transitions into what is meant to be the climax of the movie and the perfect opportunity for Ali to evolve—that is, Ali’s decision to become a conscientious objector to the Vietnam War. Stripped of his title and the ability to box in almost every state, Ali turns to public speaking as a means of support. Siegel very capably shows the irony of Ali’s trial: the effort to silence him actually forced him to speak more clearly. Siegel uses oftentimes moving and understated footage of Ali struggling through his first few speeches, stumbling against college students with long and pointed questions. And yet, in this supposedly formative moment, it’s hard to find any change deeper than basic speaking skills. Ali’s presentation evolves but his message remains the same: this last and greatest challenge provides only the most superficial development, and Siegel ultimately celebrates that our hero seems unaffected by his struggles.

“The Trials of Muhammad Ali” gives us a portrait of Ali’s courageous convictions and an energized account of the public efforts to suppress, change, and demean those beliefs. But Siegel does this without questioning the beliefs themselves, or exploring where they came from. Even at the end of the movie, when Ali is very clearly different (at the Olympics again, but this time visibly suffering from Parkinson’s), Siegel seems eager to tell us that he’s somehow still the same. If Ali ever does change, it is only to better become what he (and we) already knew him to be; that is, Siegel presents every trial as an opportunity for Ali to somehow become “more himself.” This film appears to glorify the transcendence and permanence of self, while deliberately ignoring the construction of self.

Kartemquin, the documentary film house behind the movie, was initially unsure whether or not to support it. As a spokeswoman from Kartemquin stated before an early screening at the DuSable Museum, Kartemquin mainly focuses on “character-driven stories,” and worried that Ali was too much of a historical figure. But this is how he comes off. Instead of developing a character who experiences climactic moments of transformation, the film glorifies Ali because he never transforms. In “The Trials of Muhammad Ali,” although the trials our hero faces rapidly change, from boxing matches to religious oppression to political disenfranchisement, Ali himself stands still.