When I’m absolutely dead you can stop,” proclaims a young unnamed French woman played by Sara Forestier, one of the main characters of Jacques Doillon’s Love Battles. Unlike the request directed at her unnamed lover and combatant (James Thierrée), the film itself never deals in absolutes. The characters’ backstories are shady, their names left undisclosed, and one gets the sense that the characters don’t understand much more than the viewers do. As the female character (referred to merely as “elle,” she/her in French) says at one point, “I want to understand my sadness.” The viewer wants to as well yet is almost always thwarted.

“I was told everywhere that this film was un-financeable, and I realized that no one wanted to make it regardless of money issues,” Doillon mused before the Chicago premiere of Love Battles at Doc Films on March 16. Dressed casually in a leather jacket, his scruffy gray hair at shoulder length, Doillon appeared at the film society at the end of a retrospective series of his work that began in early January. Yet despite the financial difficulties, Doillon said, he believes Love Battles is one of the five or six most important films he’s created. Considering that he has over forty director credits to his name, this is no mean distinction.

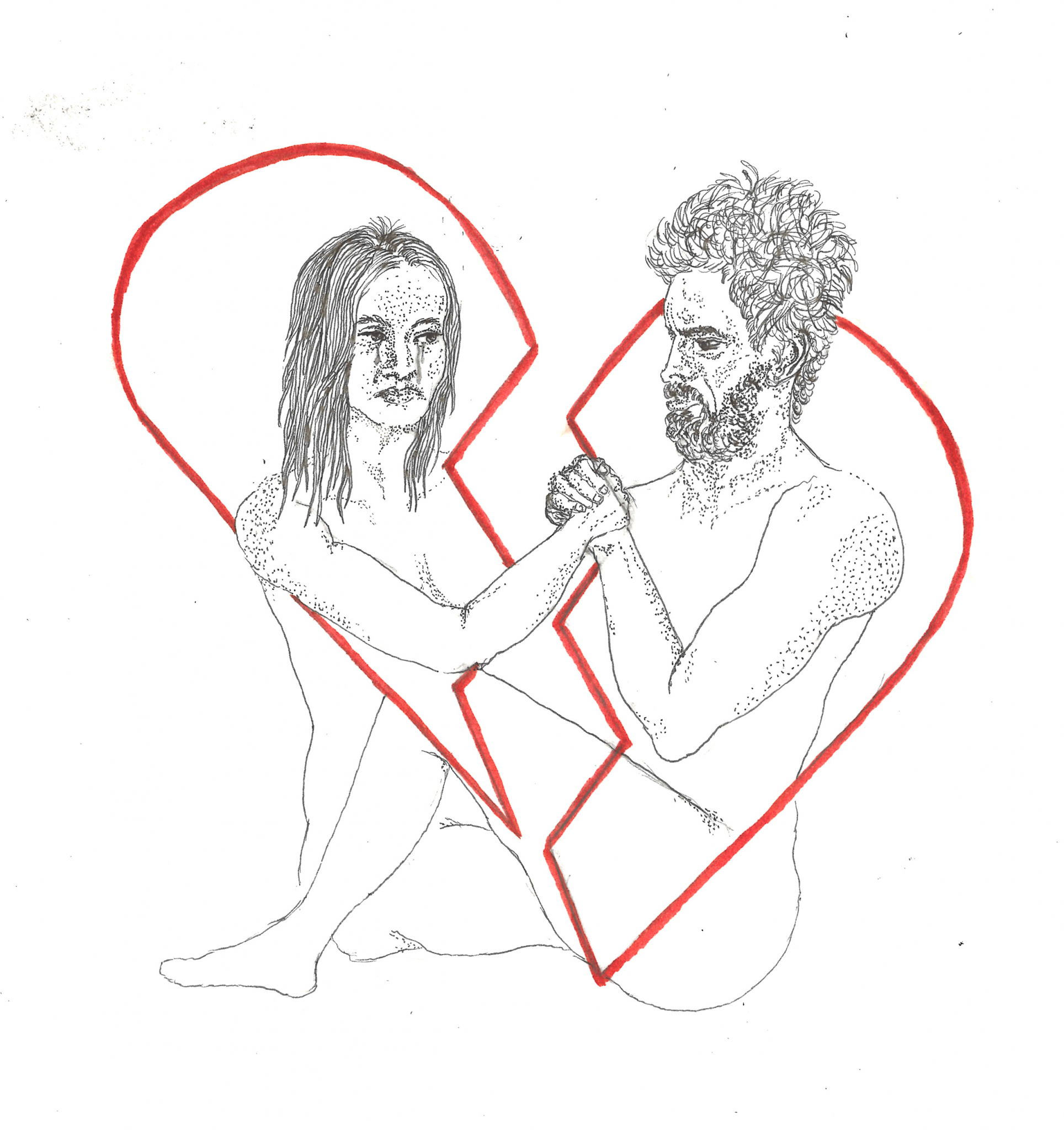

Though a renowned director, Doillon’s most recent film had problems finding financing and distribution due to the taboo mix of graphic sexual content and depiction of a couple engaged in “love battles,” physical fights. These battles, brawls interspersed with kissing and eventually sex, range widely in emotion and tone. At moments they are terrifying, such as when the man slams the woman’s head into a cabinet and for a second any playfulness disappears; at other times their violence is replaced by tender kisses and embraces.

Doillon has focused on uncomfortable and unmarketable projects throughout his career, perhaps most famously in Ponnete, a film about a four-year-old girl dealing with the death of her mother and featuring almost entirely amateur child actors. However, unlike Ponette, death is almost never on the surface of Love Battles; it lurks in the peripheries and flows in the subtext instead. Although Elle’s father has died right before the beginning of the film, she seems to worry more about her past relationship with her father than his death. The event forces her to reconsider not mortality, but love, of different varieties and from different people. Yet there is always a hint of pain, a hint of something that cannot be fixed, a deep-seated bitterness.

“Don’t expect love…love sounds obscene when you say it,” Elle mentions at one point, her voice laced with condescension that encapsulates the competitive dynamic present between the two in many scenes even when they aren’t fighting. They are constantly challenging each other, yet at moments, their antagonism disappears and they melt into each other’s embraces, lips and bodies melding. There is a radical tenderness in these moments that is part of the film’s determination to treat its two characters as human beings, not creatures defined by their battles, their situations, or their sadness.

Body language and placement is used throughout the film in the way that words or technical manipulations are often used in mainstream cinema. As Doillon said after the film, “It seems to me that bodies need to speak…at the risk of sounding pretentious, it’s like choreography.” To achieve this, Doillon asked a lot of the main actors’ bodies. They slide along hardwood floors on their backs, roll in muddy rivers. At one point the man lifts the woman up high enough that she can drape her legs over his shoulders and straddle his head, her groin in his face. All of this besides the pugnacious bits where, among other things, the two punch, scratch, slap, throttle, crush, and wrestle each other. And much of this they do in varying degrees of nudity.

The film required an extreme level of intimacy and trust, not to mention physical fitness. The actors who finally agreed to the roles were in fact dating (although Doillon noted that he was worried throughout the filming process that the two would break up, which they eventually did two weeks after filming ended), and their creative role in the film is almost equal to the director’s. Doillon dreamed the thing up, but Forestier and Thierrée built it with their bodies and their sweat. In the Q&A after the screening, some audience members wondered if using actors in this way was exploitative. Doillon responded, “If filmmakers can no longer steal from their actors, where are we going?”

Love Battles has a renegade, rebellious feel to it; its ambition and the director’s unflagging dedication to an idea echoes other adventurous filmmakers such as Werner Herzog, except instead of dragging a steamship over a mountain, Doillon turns his focus to something much more intimate and personal, almost anti-epic. Most shots in the film are shot from a relatively close to medium range, keeping the background to a minimum. And only five actors appear in the film in all.

With characteristic wit, when asked what he planned to do next, Doillon replied that he planned to exit the theater to great applause. Regardless of applause, Doillon received a surprising number of positive comments for a film that has garnered so little support thus far. One audience member said that after seeing much of Doc’s series, it was his favorite Doillon film, and even went as far as to ask how he could financially help Doillon make more films.

It’s of course impossible to know how many audience members hated the film and didn’t speak up, or how many merely felt a bit more tepid. Doillon himself is quite aware that the film is not for everyone. As he mentioned, probably only around 150,000 people have seen the film, and probably only 10,000 of them liked it. That, he said, was enough for him.

Love Battles is a film that does not justify its existence through audience response. It is a film that may make viewers feel uncomfortable and strange; it is a film that does not pass judgment on the more “strange” or unconventional aspects of its characters. Many viewers may find the characters distasteful, but Doillon does not. That isn’t his job.

“Being a filmmaker is complicated enough,” he said. “To aspire to be a moralist or something else is not something I can do.” Doillon says he sees his work mainly as technical. He constructs films, and organizations like Doc Films set them up on a screen. It’s up to the audience to decide what to do with them.