On a cold Saturday afternoon, eight-year-old Melissa Ortega and her mother, Araceli Leaños, left home walking to the bank and then to a McDonald’s. Araceli wanted to keep her promise. She was going to get her girl a hamburger. It was January 22, 2022.

Melissa: ¿Me compras una hamburguesa, mamá?

Mamá: Claro que sí, mami, ¿quieres ir ahora o después de ir al banco?

Melissa: Al rato, todavía no tengo hambre, pero ¿me prometes que me la compras?

Mamá: Claro que sí. Te lo prometo.

(Melissa: Mom, can you buy me a hamburger?

Mom: Do you want to go now or after going to the bank?

Melissa: We can go later, I am not that hungry right now, but promise me you’ll buy me one?

Mom: Of course. I promise.)

Sixteen-year-old Emilio Corripio stepped out from an alley, shooting at rival gang members. Caught in the crossfire were Melissa and her mother Araceli. According to police, the mother and daughter ran towards the bank as Corripio shot one of his targets in the back, a twenty-six-year-old gang member. Inadvertently, the teenaged shooter had also shot Melissa in the head twice. She would collapse and die just a few hours later at Stroger Hospital.

It was eerily reminiscent of another tragedy just over two years prior. In 2019, on Halloween night, a fifteen-year-old boy raised his gun to kill a rival gang member in La Villita. Shooting wildly, he missed him but hit seven-year-old Giselle Zamago, in her Minnie Mouse costume, in the neck and chest. She was trick-or-treating with her dad. Miraculously, she survived.

I am reminded I was five years old when my family and I immigrated to the United States. On the night that we waited to cross from Tijuana to San Diego, I asked my mother to tell me what was on the other side. She responded that Mickey Mouse was there and she promised I’d meet him. Of course, I am aware now that she could have only kept this promise if we didn’t get arrested or died trying to cross into America for its promise of providing its children a bright and safe future.

Melissa immigrated with her mother from Tabasco, Zacatecas, to California. Three months later they moved to Chicago, where most of their family lives. Melissa became a third grade student at Emiliano Zapata Academy. Pastor Matt DeMateo from New Life Ministries read her mother’s statement during a press conference: she dreamed of learning English, doing TikTok dances with friends, and seeing Chicago snow for the first time, which she was able to live out during a brief snowfall in late December.

Armed conflict, natural disasters, gender inequality, unemployment, corruption, and lack of access to healthcare and quality education are many of the reasons immigrants come to the U.S. La Villita has been a port of entry for many Mexican immigrant families looking for a better life, like Melissa and her family. And for decades, Mexican immigrants have created and sustained the second-highest tax revenue generating shopping district in the city with over 500 businesses, contributing $900 million per year to Chicago’s economy. While La Villita residents have generated whopping amounts to the local economy, it is unclear how much of this money comes back to the community.

Something desperately needed is additional investment in violence prevention. While there was an increase in the City’s violence prevention spending for 2022, up from $85 million in comparison to the previous year’s $16.5 million, police spending soared to $1.9 billion–a $200 million increase from a year prior.

“We could do a lot more if we reallocated some of those [police] funds,” said Jesus Salazar, a field manager in crime prevention with Metropolitan Family Services (MFS). Salazar said a focus on street outreach is key to violence prevention which involves reaching out to gang-involved youth and providing them with access to resources.

Salazar was a “violence interrupter” with CeaseFire from 2011 to 2015. His responsibility was to mitigate and de-escalate violence on the ground. CeaseFire, originating in Chicago, was funded by the State of Illinois, and due to its positive impact, its model had spread nationally to other major cities. However, “Governor Rauner deemed the program non-essential, and he snatched away the funding,” Salazar said.

Even when operating, the organization was inconsistent, and outreach workers didn’t find it sustainable. “We would be off for six months, and then we would be off for another three months, and then [they’d] bring us on for another six months,” Salazar said. “It was hectic.”

As a field manager with MFS, Salazar now works with outreach workers who intervene in gang conflicts. This involves mediation, setting up non-aggression agreements and offering support to teens and adults affiliated in gangs in order to get them to put down the guns. “I don’t think the police can do that,” he said. “They don’t have relationships… they’re not from our community. We spent a lot of money on the police, and I don’t think we’ve seen the results.”

Melissa’s tragic murder, along with many other killed children, has put a renewed pressure on officials demanding more funding and pointing to the shortcomings of the city and the state. Araceli Leaños, Melissa’s mother, expressed this sentiment in a written statement to the press. She even went on to say she “forgives” the gunman who killed her daughter, calling him a “victim, too.”

The sixteen-year-old who killed Melissa got back into a vehicle, which sped away, but was eventually tracked down through license-plate readers and surveillance footage. The teen faces felony counts of first-degree murder and attempted first-degree murder, along with two counts of aggravated assault with a firearm. The driver, twenty-seven-year-old Xavier Guzman, was also arrested and faces felony charges for first degree murder and attempted first degree murder. He is also charged with one count of aggravated unlawful use of a weapon.

Salazar thinks looking at the root of the problem can shed light on finding solutions to gun violence such as poverty, problems at home, and learning disabilities. However, he said, one of the biggest reasons young people turn to gangs is for support—because that support doesn’t exist anywhere in their lives. There aren’t enough positive role models to emulate as well, he added. And while there may be sports and activities teens can be a part of, “they still have to go home” and “back to the community” where, he said, they can get pulled back into crime.

Growing up in La Villita, he said that he met a few positive role models, but he couldn’t relate to them. “How many young kids are looking up to a pastor, right?” he asked. “Young people aspire to be what they see on television: to be: ‘cool,’ ‘sexy,’ and ‘tough.’ There isn’t a counternarrative to that, and it’s disappointing,” he added.

Salazar thinks it’s also important to have outreach workers at schools because as soon as a child acts out, they get reprimanded by getting suspended or expelled. “But is that the right thing to do for one of these young brothers? Like, you need to stop a young brother from learning and getting an education?” he said.

Before doing outreach work, Salazar was affiliated with a gang in Little Village for decades. He calls this “fall[ing] into a rabbit hole for acting out.” He said it was a GED teacher who helped him push through learning challenges in math, and the teacher took the time to ask him, “What’s going on… why are you acting out?”

He thinks these types of interactions are important when children don’t have a support system and “don’t feel loved.” Getting that love from people in the community also helped him. He was able to get a job, and he received focused attention by a mentor. This kind of support wasn’t available to him in other places.

A lot more resources are needed to supplement existing programs, said Kaya Nuques, executive director at Enlace Chicago, a La Villita nonprofit that focuses on education, health, immigrant rights, and violence prevention. “There is an overwhelming number of youth and adults who need support, and there is limited capacity.”

The CeaseFire program, which Enlace ran, also used several strategies to target violence, including the provision of services such as GED programs, counseling, drug and/or alcohol treatment, and helping young people find jobs.

Salazar said that in order to get young boys to put their guns down, the guns must be replaced with something else, and said violence prevention is an effective approach to help unravel that loop. “I don’t want the next generation of young people to continue to perpetrate this, this cycle of violence,” Salazar said. “Because, you know, their uncle was killed, their dad was killed, their little brother was killed, and they don’t know how to grieve.”

According to Salazar, the state reallocated the funds for CeaseFire to organizations like MFS and Chicago CRED that do similar work. With a jump in funds for crime prevention in this year’s budget, he hopes street outreach will be a big priority.

The solution goes beyond street outreach, according to Dolores Castañeda. Castañeda is a Little Village resident involved with Padres Angeles (Parent Angels), an organization that promotes peace in the community and helps families heal after they’ve lost loved ones due to gun violence.

Though she had worked in several factories in Chicago, Castañeda permanently immigrated to the U.S. about thirty years ago. The impetus was death threats from the president of her village of Salvatierra in Guanajuato, Mexico, when she began writing about and exposing corruption and abuse in local jails. Her mother had, many years ago, immigrated to the U.S. to find work as a street vendor to provide for Castañeda and her brothers back home. Her father had passed away, making it difficult for her mother to support all of the children. Growing up, she said, she became aware of the poverty in her pueblo. “I learned from a very young age [about the] barriers that I had in my village, where I was born, where people died because they didn’t have food or medicine.”

Casteñada is now a mother of four. She was at her job when her then-twelve-year-old daughter got caught in a crossfire between rival gang members and was shot. She survived, but the incident made her want to get involved in violence prevention. She said more funding programming is needed in Little Village in addition to what is provided by the City, which she described as being directed more to funerals and helping families cope, rather than actual prevention.

She worries that often the blame in a situation like this is put on the parents–especially the mother. She said she knows many parents who have lost children that continue to blame themselves. “There is a situation of blaming the victim for the fact that your child has been shot,” she said. “That it’s your fault.” This type of mentality doesn’t allow parents to properly heal, she said, and so the community and City officials don’t feel the pressure to step in.

Understanding why young people are picking up guns in the first place can provide a gateway to tackling violence. And while the police will take a gun away from the hands of these young boys, Salazar said that can be addressed through prevention programs in the community and outreach workers in schools. Castañeda thinks it’s important to support parents, not attack them, to quit blaming them and to make better use of City funds by investing in spaces for young people and families. “The money should really go to the community, not [just] to pay for funerals,” Castañeda added, referencing large organizations that decide where the money goes.

22nd Ward Alderperson Michael Rodríguez said tackling gun violence is a collective issue and everyone needs to be in on it: “It’s not about any one person. It’s about all of us together. So I’ve made it a point,” mentioning his background as a former director of violence prevention and executive director at Enlace, a former employee at the Cook County Medical Examiner’s Office, and a youth mentor during his college days. Over the years, Rodríguez said, “we’ve been able to increase the City’s budget going towards violence prevention, intervention work, but it’s not nearly enough.”

He agrees more resources towards prevention and intervention are effective and “economically sound.” He said, “It costs a lot more money to incarcerate people.” He said he will continue working on crime prevention with a lens on poverty reduction which he references as a root cause of gun violence.

Along with poverty reduction, Rodriguez said his focus will be working with Eddie Bocanegra, a Chicago violence-prevention leader from Little Village who was recently appointed as an advisor to the U.S. Justice Department.

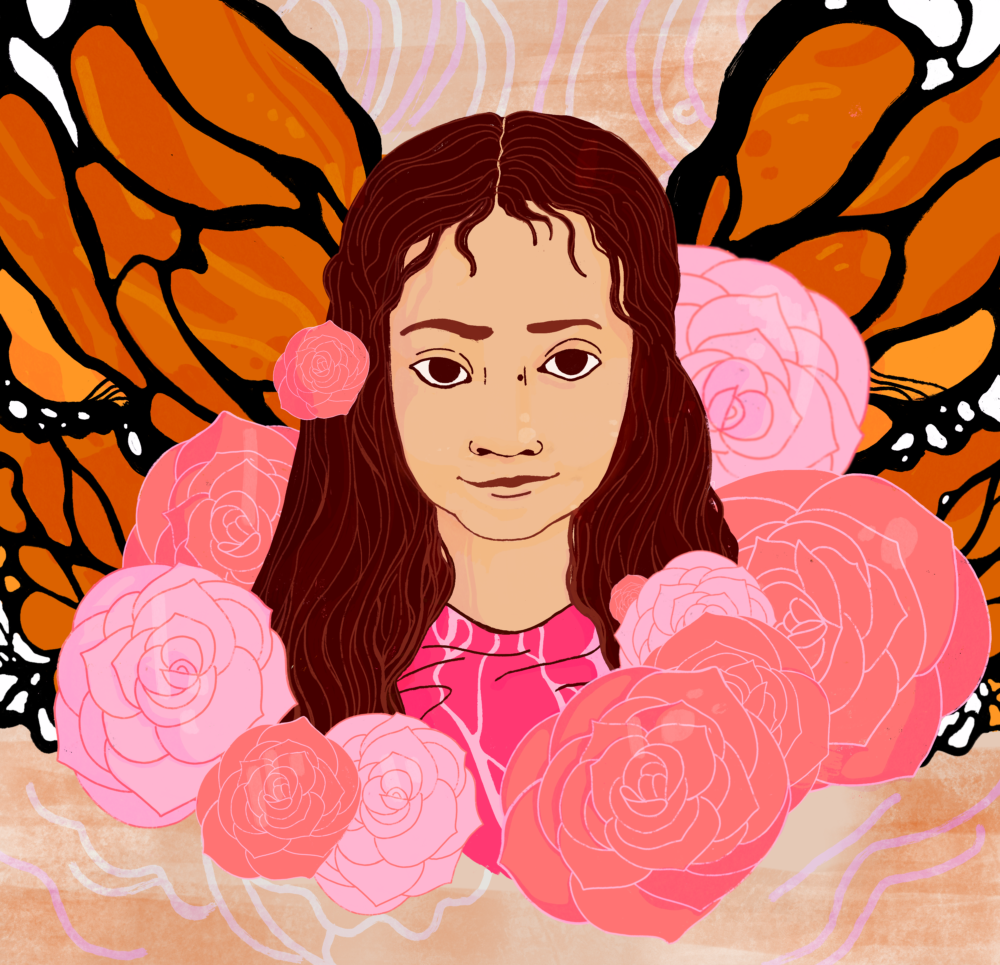

A drawing of Melissa, created by local artist Michelle Rivera, peaked above a crowd marching for peace down 26th Street a week after her death. In the drawing, Melissa is surrounded in white roses. She is wearing a white gown and a halo hangs above her head. Bright orange and black monarch butterfly wings are drawn on her. For undocumented immigrants living in the U.S., the monarch butterfly represents dignity and resilience, and the inherent right that all people have to move and travel freely. Dozens of children walked alongside parents holding pink and white balloons, as well as roses. Squad cars surrounded the marchers. The group then gathered at the corner of Pulaski Avenue where they placed the roses on the street corner next to candles and released balloons into the sky.

Correction, February 10, 2022: An earlier version incorrectly stated the age of one of the children in this story.

Correction, February 13, 2022: The story has been updated to include the name of the artist that created the portrait of Melissa Ortega referenced in the story.

Alma Campos is the Weekly’s immigration editor. She last wrote about Jesús “Chuy” Negrete, a Chicago folklorist, writer, and activist known for singing corridos who passed away in the summer of 2021.