Chicago is one of the cultural powerhouses of the world,” muses Mark Kelly, the newly appointed Commissioner of the Department of Cultural Affairs and Special Events. “We have thousands of great artists and so we need to support our artists, we need to value our artists and then…they can…make our city a better place by bringing their art onto the streets.” Kelly is referring to the 50×50 Neighborhood Project, a Year of Public Art initiative announced by Mayor Rahm Emanuel in late 2016 to install public art in every ward in Chicago in 2017.

The Year of Public Art is an initiative committed to bringing more public art into the city as a whole. It’s also, in part, a celebration of the fiftieth anniversary of two of Chicago’s most famous public art pieces: the “Chicago Picasso” in Daley Plaza and the “Wall of Respect,” a mural that once existed at 43rd Street and Langley Avenue and is largely regarded as the beginning of the community mural movement in Chicago.

Both pieces introduced new forms of art into the public arena. The “Wall of Respect” brought awareness to Black artists and historical figures in a very public way, and the “Picasso” brought modern art, typically seen only in museums, into everyday life. “People were horrified when they first saw it,” Kelly said, but he now considers the Picasso one of the “most beloved” elements of Chicago’s downtown.

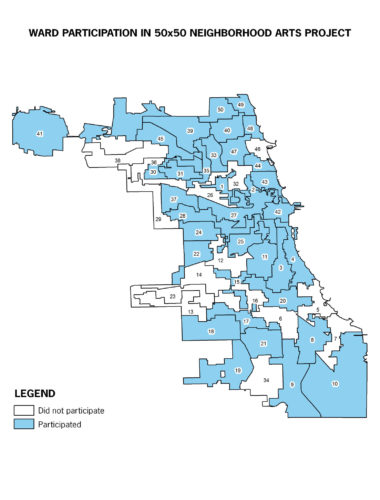

As a part of the 50×50 program, each alderman could choose to contribute $10,000 to a public art project, which would in turn be matched dollar for dollar by the mayor’s office. Due to the nature of the funding, however, some wards opted out of the program to save their often tight budgets for what 2017 menu allotments are typically reserved for: infrastructure maintenance and more tangible improvements to their wards, such as filling potholes. As reported by the Weekly in March, some were concerned the funding would make the initiative inaccessible to some wards. At the time, thirty-eight wards confirmed participation. Out of the fifty wards, thirty-five ended up deciding to participate in the program, bringing fresh public art to a substantial portion of the city. Of the fifteen that did not participate, nine are on the South and West Sides. Proposals and completed projects range from murals to dance performances to large sculptural installations—making for an exciting combination of artwork reflecting the variety of forms that the fiftieth anniversary honors.

The Weekly sat down with artists and organizers from three of the completed projects for wards on the South Side.

Woodlawn Mural, 20th Ward

“Woodlawn has a reputation amongst people outside of the community for being a dangerous place…I think the residents were really interested in changing that perception,” mural artist Devin Torres said. The 20th Ward’s public art installation is a mural at 65th and Dorchester.

The mural, at nearly 4,200 square feet, is “a long reflection on the past and present through images and patterns.” It incorporates well-known individuals from the community, including famed Chicago musician Minnie Riperton. She’s one of the many figures and accomplishments you see as you walk along the mural to its end, which depicts modern Woodlawn using images of birdwatchers, impassioned protesters, and residents enjoying their outdoor space.

Torres was the lead artist on the project. He’s a teaching artist with Green Star Movement, the nonprofit group that was selected by the Ward to complete the mural with Woodlawn.

“Residents wanted to demonstrate their community has produced positive things and people in the past, and they will continue to do so in the future,” Torres said. “They wanted to show people they had something to be proud of.”

The design was a collective effort of Woodlawn residents and Green Star Movement artists. Residents submitted ideas and themes they wanted to see on the wall and eventually voted on which compilation was most representative of those ideas.

The choice of mosaic tile as the medium meant the mural required exceptional community participation in order to meet Woodlawn’s early October deadline. When over 1,000 volunteers ended up showing up to help throughout the process, Torres was blown away.

“People would just hang out, they would cheer us on, they would bring us snacks or play music if they weren’t working on the wall,” Torres said.

Why were residents so committed to this project? “Public art such as this mural has the ability to create spaces that may not exist,” Torres said. “It brings a collective idea on what a community would like to reflect about themselves and makes that [idea] clear to the world.”

Pullman Mural, 9th Ward

Rahmaan Barnes is a Chicago-based artist working as a muralist and graphic designer. Starting off as a graffiti artist in middle school, Barnes eventually progressed into larger scale public art projects as a teen; he has been a staple in the city’s public art community for years.

Having spent his high school years in Pullman, Barnes is familiar with the challenges the community faces in terms of violence. As he approached the Pullman public art installation, he was committed to creating something that residents could be proud of—and “something to focus on to remember the brighter side of things,” Barnes said.

Barnes held three community meetings to present sketches and ideas to interested residents. During this process, the railroad industry and community organizing emerged as points of pride in the community. “It was important to everyone to make it clear there was no question about what had been achieved here,” said Barnes, “and [to] pay homage to all the people who worked at [the Pullman factories] and made that success possible.”

In creating the mural, Barnes enlisted over seventy high school students to assist in painting the larger portions. He wanted the mural to be a source of creative expression for the community as well as a source of continual inspiration. He wanted the process of creating the piece to be therapeutic in and of itself.

“I have noticed a lot of people in our…lower income communities are lacking a creative outlet, creative expression in any way. This mural allowed for some young people to come out and fulfill that need for creativity,” Barnes said. “Having a creative outlet on a daily basis is like a mandatory mental exercise that keeps you grounded in this chaotic world we live in.”

The final product, standing twelve feet high, is an expansive 160-foot sepia-toned mural depicting images of factory workers, train porters, and Barack Obama (who started out as a community organizer in the Pullman neighborhood). Barnes chose the sepia tone so it would age in a way that could be transformed over time, just as Pullman has, since many of these images were the reality of the neighborhood. When gazing at this mural, it is without question what a profound legacy the Pullman community has had on Chicago, transportation, and beyond.

Pilsen Mural, 25th Ward

At the corner of 21st and Peoria stands an oasis known as El Paseo Community Garden. The garden is known for its monthly outdoor yoga sessions and work on monarch butterfly preservation—a butterfly famous for its journey from Mexico to the Midwest. The garden also happens to be one of the first stops on the controversial El Paseo Trail and the spot chosen for the 50×50 mural in Pilsen.

Artists Eric J. Garcia, Diana Solís, and Katia Pérez-Fuentes had a large task in front of them: to design a mural that was representative of a rapidly changing community, and to honor the traditions of public art in Pilsen.

The artists decided to hold three separate meetings: one for individuals who had lived in the community and participated in the garden for years, one for “the gardeners” or the main planters in the garden, and an open meeting for all residents of Pilsen. Consistent themes began emerging through these meetings: immigration, erasure of previous works and identities, environmental issues and contamination, and, of course, the butterfly.

Knowing many residents were concerned the mural would be a driving force in further development and gentrification along El Paseo Trail, Garcia, Solís, and Pérez-Fuentes made sure those who had participated in the meetings felt heard and reflected in the work. “If there are things that are going up that don’t reflect you or you’re not comfortable with, it gives you a sense of who has power and who has ownership over that space,” Pérez-Fuentes said.

The outcome was a 2,700 square-foot piece that took over fourteen weeks to complete. Sixty community members came out to help at an all-day community paint day, and garden organizer Paula Acevedo described the project as “a mural by the community and for the community.”

The wall both alludes to and depicts the struggles and growth community members outlined as important to them. There are layers of different landscapes overlaid with barbed wire as a reference to immigration and migration, images of industry, and symbols of growth, prosperity, and community.

Laid over the entire piece is a subtle, yet important, homage to murals that no longer exist—including the famed Casa Aztlan painted subtly over in gold. “There were several murals that came down while we were developing this mural,” Pérez-Fuentes said. “It was our responsibility to honor them, and ensure the people who made them would not be forgotten.”

Support community journalism by donating to South Side Weekly